chonticha wat/iStock via Getty Images

Money is a surprisingly complex subject.

People spend their lives seeking money, and in some ways it seems so straightforward, and yet what humanity has defined as money has changed significantly over the centuries.

How could something so simple and so universal, take so many different forms?

Flaticon

It’s an important question to ponder because we basically have four things we can do with our resources: consume, save, invest, or share.

Consume: When we consume, we meet our immediate needs and desires, including shelter, food, and entertainment.

Save: When we save, we store our resources in something that is safe, liquid, and portable, a.k.a. money. This serves as a low-risk battery of future resource consumption across time and space.

Invest: When we invest, we commit resources to a project that has a decent likelihood of multiplying our resources but also comes with a risk of losing them, by trying to provide some new value to ourselves or others. This serves as a higher-risk, less-liquid, and less-portable amplifier of future resource consumption potential compared to money. There are personal investments, like our own business or education, and there are external financial investments in companies or projects led by other people.

Share: When we share, or in other words give to charity and those in our community, we give some portion of our excess resources to those that we deem to be needing and deserving. In many ways, this can be considered a form of investment in the ongoing success and stability of our larger community, which is probably why we are wired to want to do it.

The majority of people in the world don’t invest in financial assets; they are still on the consumption stage (basic necessities and daily entertainment) or the saving stage (money and home equity), either due to income constraints, consumption excesses, or because they live in part of the world that doesn’t have well-developed capital markets. Many of them do, however, invest in expanding a self-owned business or in educating themselves and their children, meaning they invest in their personal lives, and they might share in their community as well, through religious institutions or secular initiatives.

Among the minority that do invest in financial assets, they are generally accustomed to the idea that investments change rapidly over time, and so they have to put a lot of thought into how they invest. They either figure out a strategy themselves and manage that, or they outsource that task to a specialist to do it for them to focus more on the skills that they earn the resources with in the first place.

However, depending on where they live in the world, people are not very accustomed to keeping track of the quality of money itself, or deciding which type of money to hold.

In developed countries in particular, people often just hold the currency of that country. In developing countries that tend to have a more recent and extreme history of currency devaluation, people often put more thought into what type of money they hold. They might try to minimize how much cash they hold and keep it in hard assets, or they might hold foreign currency, for example.

This article is the first in a three-part series that looks at the history of money, and examines this rather unusual period in time where we seem to be going through a gradual global transformation of what we define as money, comparable to the turning points of 1971-present (Petrodollar System), 1944-1971 (Bretton Woods System), the 1700s-1944 (Gold Standard System), and various commodity-money transition periods (pre-1700s). This type of occasion happens relatively rarely in history for any given society but has massive implications when it happens, so it’s worth being aware of.

If we condense those stages to the basics, the world has gone through three phases: commodity money, gold standard (the final form of commodity money), and fiat currency.

A fourth phase, digital money, is on the horizon. This includes private digital assets (e.g. bitcoin and stablecoins) and public digital currencies (e.g. central bank digital currencies) that can change how we do banking, and what economic tools policymakers have in terms of fiscal and monetary policy. These assets can be thought of as digital versions of gold, commodities, or fiat currency, but they also have their own unique aspects.

This article series walks through the history of monetary transitions from the lenses of a few different schools of thought (often at odds with each other), and then examines the current and near-term situation as it pertains to money and how we might go about investing in it.

- Chapter 1: Commodity Money

- Chapter 2: Fiat Currency

- Chapter 3: Digital Assets

Some people whose work I’ve drawn from for this article series, from the past and present, include Carl Menger, Warren Mosler, Friedrich Hayek, Satoshi Nakamoto, Adam Back, Saifdean Ammous, Vijay Boyapati, Stephanie Kelton, Ibn Battuta, Emil Sandstedt, Robert Breedlove, Ray Dalio, Alex Gladstein, Elizabeth Stark, Barry Eichengreen, Ross Stevens, Luke Gromen, Anita Posch, Jeff Booth, and Thomas Gresham.

Commodity Money

Money is not an invention of the state. It is not the product of a legislative act. Even the sanction of political authority is not necessary for its existence. Certain commodities came to be money quite naturally, as the result of economic relationships that were independent of the power of the state.

-Carl Menger, 1840-1921

Barter occurred throughout the world in various contexts going back tens of thousands of years or more.

Eventually, humans began to develop concepts and technologies that allowed them to abstract that process. The more complex an economy becomes, the greater the number of possible combinations of barter you can have between different types of goods and services providers, so the economy starts requiring some standard unit of account, or money.

Specifically, the society begins requiring something divisible and universally acceptable. An apple farmer, for example, that needs some tools (a blacksmith), meat (a cattle rancher), repair work (a carpenter), and medicine for her children (a doctor), can’t spend the time going around finding individuals that have what she needs, that also happen to want a ton of apples. Instead, she simply needs to be able to sell her highly seasonal apples for some unit, that she can use to save and buy all of those things with over time as she needs them.

Money, especially types of money that take work to produce, often seems arbitrary to outsiders of that culture. But that work ends up paying for itself many times over, because a standardized and credible medium of exchange and store of value makes all other economic transactions more efficient. The apple farmer doesn’t need to find a specific doctor who wants to buy a ton of apples for his expensive services right now.

A number of economists from multiple economic schools have pondered and formulated this concept, but commodity money as a topic tends to come up the most often by those in the school of Austrian Economics, founded by Carl Menger in the 1800s.

In this way of thinking, money should be divisible, portable, durable, fungible, verifiable, and scarce. It also usually (but not always) has some utility in its own right. Different types of money have different “scores” along those metrics.

- Divisible means the money can be sub-divided into various sizes to take into account different sizes of purchases.

- Portable means the money is easy to move across distances, which means it has to pack a lot of value into a small weight.

- Durable means the money is easy to save across time; it does not rot or rust or break easily.

- Fungible means that individual units of the money don’t differ significantly from each other, which allows for fast transactions.

- Verifiable means that the seller of the goods or services for the money can check that the money is what it really appears to be.

- Scarce means that the money supply does not change quickly, since a rapid change in supply would devalue existing units.

- Utility means that the money is intrinsically desirable in some way; it can be consumed or has aesthetic value, for example.

Summing those attributes together, money is the “most salable good” available in a society, meaning it’s the good that is the most capable of being sold. Money is the good that is most universal, in the sense that people want it, or realize they can trade for it and then easily and reliably trade it for something else they do want.

Other definitions consider money to be “that which extinguishes debt”, but debt is generally denominated in units of whatever money is defined to be at the time the debt was issued. In other words, debt is typically denominated in units of the most salable good, rather than the most salable good being defined as what debt is denominated in. Indeed, however, part of the ongoing network effect of what sustains a fiat currency system is the large amount of debt in the economy that creates sustained ongoing demand for those currency units to service those debts.

Back in 1912, Mr. J.P. Morgan testified before Congress and is quoted as having said the famous line:

Gold is money. Everything else is credit.

In other words, although their terms often overlap, currency and money can be thought of as two different things for the purpose of discussion.

We can define currency as a liability of an institution, typically either a commercial bank or a central bank, that is used as a medium of exchange and unit of account. Physical paper dollars are a formal liability of the US Federal Reserve, for example, while consumer bank deposits are a formal liability of that particular commercial bank (which in turn hold their reserves at the Federal Reserve, and those are liabilities of the Federal Reserve as well).

In contrast to currency, we can define money as a liquid and fungible asset that is not also a liability. It’s something intrinsic, like gold. It’s recognized as a highly salable good in and of itself. In some eras, money was held by banks as a reserve asset in order to support the currency that they issue as liabilities. Unlike a dollar, which is an asset to you but a liability of some other entity, you can hold gold which is an asset to you and a liability to nobody else.

Under gold standard systems, currency represented a claim for money. The bank would pay the bearer on demand if they came to redeem their banknote paper currency for its pegged amount of gold.

Scarcity is often what determines the winner between two competing commodity monies. However, it’s not just about how rare the asset is. A good concept to be familiar with here is the stock-to-flow ratio, which measures how much supply there currently exists in the region or world (the stock) divided by how much new supply can be produced in a year (the flow).

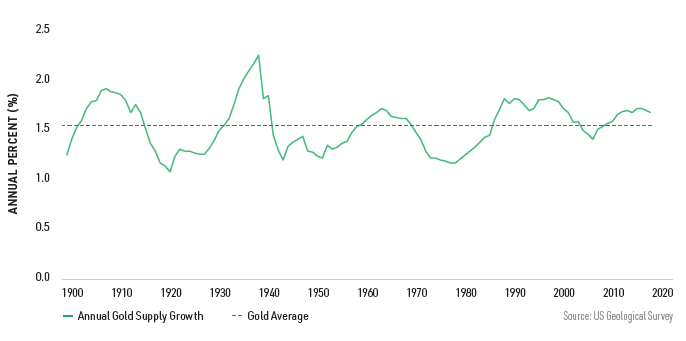

For example, gold miners historically add about 1.5% new gold to the estimated existing above-ground gold supply each year, and the vast majority of gold does not get consumed; it gets re-melted and stored in various shapes and places.

NYDIG

This gives gold a stock to flow ratio of 100/1.5 = 67 on average, which is the highest stock-to-flow ratio of any commodity. The world collectively owns 67 years worth of average annual production, based on World Gold Council estimates. Let’s call it about 60 or 70 since this isn’t exact.

If a money (the most salable good) is easy to create more of, then any rational economic actor would just go out and create more money for herself, diluting the whole supply of it. If an asset has a monetary premium on top of its pure utility value, then it’s strongly incentivizing market participants to try to make more of it, and so only the forms of money that are the most resistant to debasement can withstand this challenge.

On the other hand, if a commodity is so rare that barely anyone has it, then it may be extremely valuable if it has utility, but it has little useful role as money. It’s not liquid and widely-held, and so the frictional costs of buying and selling it are higher. Certain atomic elements like rhodium for example are rarer than gold, but have low stock-to-flow ratios because they are consumed by industry as quickly as they are mined. A rhodium coin or bar can be purchased as a niche collectible or store of value, but it’s not useful as societal money.

So, a long-lasting high stock-to-flow ratio tends to be the best way to measure scarcity for something to be considered money, along with the other attributes on the list above, rather than absolute rarity. A commodity with a high stock-to-flow ratio is hard to produce, and yet a lot of it has already been produced and is widely distributed and held, because it either isn’t rapidly consumed or isn’t consumed at all. That’s a relatively uncommon set of attributes.

Throughout history various stones, beads, feathers, shells, salt, furs, fabrics, sugar, coconuts, livestock, copper, silver, gold, and other things have served as money. They each have different scores for the various attributes of money, and tend to have certain strengths and weaknesses.

Salt for example is divisible, durable, verifiable, fungible, and has important utility, but is not very valuable per unit of weight and not very rare, so doesn’t score very well for portability and scarcity.

Gold is the best among just about every attribute, and is the commodity with by far the highest stock-to-flow ratio. The one weakness it has compared to other commodities is that it’s not very divisible. Even a small gold coin is more valuable than most purchases, and is worth as much as most people make in a week of labor. It’s the king of commodities.

For a large portion of human history, silver has actually been the winner in terms of usage. It has the second-best score after gold across the board for most attributes, and the second highest stock-to-flow ratio, but beats gold in terms of divisibility, since small silver coins can be used for daily transactions. It’s the queen of commodities. And in chess, the king may be the most important piece, but the queen is the most useful piece.

In other words, gold was often held by the wealthy as a long-term store (and display) of value, and as a medium of exchange for very large purchases, while silver was the more tactical money, used as a medium of exchange and store of value by far more people. A bimetallic money system was common in many regions of the world for that reason until relatively recently, despite the challenges that come with that.

The scarcity of some of the other commodities have more specific weaknesses as it relates to technology. Here are two examples:

Rai Stones

Inhabitants of a south-Pacific island called Yap used enormous stones as money. These “rai stones” or “fei stones” as they were called were circular discs of stone with a hole in the center, and came in various sizes, ranging from a few inches in diameter to over ten feet in diameter. Many of them were at least a couple feet across, and thus weighed hundreds of pounds. The biggest were over ten feet across and weighed several thousands of pounds.

Interestingly, I’ve seen this example used by both an Austrian economist (Saifedean Ammous) and an MMT economist (Warren Mosler). The reason that’s interesting is because those two schools of thought have very different conceptions of what money is.

Anyway, what made these stones unique was that they were made from a special type of limestone that was not found in abundance on the island. Yap islanders would travel 250 miles to a neighboring island called Palau to quarry the limestone and bring it back to Yap.

They would send a team of many people to that far island, quarry the rock in giant slabs, and bring it back on wooden boats. Imagine bringing a multi-thousand pound stone across 250 miles of open ocean on a wooden boat. People died in this process over the years.

Once made into rai stones on Yap, the big ones wouldn’t move. This is a small island, and all of the stones were catalogued by oral tradition. An owner could trade one for some other important goods and services, and rather than moving the stone, this would take the form of announcing to the community that this other person owned the stone now.

In that sense, rai stones were a ledger system, not that different than our current monetary system. The ledger keeps track of who owns what, and this particular ledger happened to be orally distributed, which of course can only work in a small geography.

By the time this was documented by Europeans, there were thousands of rai stones on Yap, representing centuries of quarrying, transporting, and making them. Rai stones thus had a high stock-to-flow ratio, which is a main reason for why they could be used as money.

In the late 1800s, an Irishman named David O’Keefe came across the island and figured this out. And, with his better technology, he could easily quarry stone from Palau and bring it to Yap to make rai stones, and thus could become the richest man on the island, able to get locals to work for him and trade him various goods.

As the Irishman got to know Yap better, he realized that there was one commodity, and only one, that the local people coveted—the “stone money” for which the island was renowned and that was used in almost all high-value transactions on Yap. These coins were quarried from aragonite, a special sort of limestone that glistens in the light and was valuable because it was not found on the island. O’Keefe’s genius was to recognize that, by importing the stones for his new friends, he could exchange them for labor on Yap’s coconut plantations. The Yapese were not much interested in sweating for the trader’s trinkets that were common currency elsewhere in the Pacific (nor should they have been, a visitor conceded, when “all food, drink and clothing is readily available, so there is no barter and no debt” ), but they would work like demons for stone money.

-Smithsonian Magazine, “David O’Keefe: the King of Hard Currency”

In essence, better technology eventually broke the stock-to-flow ratio of rai stones by dramatically increasing the flow. Foreigners with more advanced technology could bring any number of them to the island, become the wealthiest people on the island, and therefore increase the supply and reduce the value of the stones over time.

However, locals were smart too, and they eventually mitigated that process. They began to assign more value to older stones (ones that were verifiably quarried by hand decades or centuries ago), because they exclude the new abundant stones by definition and thus maintain their scarcity. Nonetheless, the writing was on the wall; this wasn’t a great system anymore.

Things then took a darker turn. As described in that Smithsonian piece:

With O’Keefe dead and the Germans thoroughly entrenched, things began to go badly for the Yapese after 1901. The new rulers conscripted the islanders to dig a canal across the archipelago, and, when the Yapese proved unwilling, began commandeering their stone money, defacing the coins with black painted crosses and telling their subjects that they could only be redeemed through labor. Worst of all, the Germans introduced a law forbidding the Yapese from traveling more than 200 miles from their island. This put an immediate halt to the quarrying of fei , though the currency continued to be used even after the islands were seized by the Japanese, and then occupied by the United States in 1945.

Many of the stones were taken and used as makeshift anchors or building materials during World War II by the Japanese, reducing the number of stones on the island.

Rai stones were a notable form of money while they lasted because they had no utility. They were a way to display and record wealth, and little else. In essence, it was one of the earliest versions of a public ledger, since the stones didn’t move and only oral records (or later, physical marks by Germans) dictated who owned them.

African Beads

As another example, trade beads were used in parts of west Africa as money for many centuries, stretching back at least to the 1300s and prior as documented by ancient travelers at the time, as recorded by Emil Sandstedt. Various rare materials could be used, such as coral, amber, and glass. Venetian glass beads gradually made their way across the Sahara over time as well.

To quote Ibn Battatu, from his travels in the 14th century (from Sandstedt’s article):

A traveler in this country carries no provisions, whether plain food or seasonings, and neither gold nor silver. He takes nothing but pieces of salt and glass ornaments, which the people call beads, and some aromatic goods.

These were pastoral societies, often on the move, and the ability to wear your money in the form of strands of beautiful beads was useful. These beads maintained a high stock-to-flow ratio because they were kept and traded as money, while being hard to produce with their level of technology.

Eventually, Europeans began traveling and accessing west Africa more frequently, noticed this usage of trade beads, and exploited them. Europeans had glass-making technology, and could produce beautiful beads with modest effort. So, they could trade tons of these beads for commodities and other goods (and unfortunately for human slaves as well).

Due to this technological asymmetry, they devalued these glass beads by increasing their supply throughout west Africa, and extracted a lot of value from those societies in the process. Locals kept trading scarce local “goods”, ranging from important commodities to invaluable human lives, for glass beads that had far more abundance than they realized. As a result, they traded away their real valuables for fake valuables. Picking the wrong type of money can have dire consequences.

It wasn’t as easy as one might suspect for the Europeans to accomplish, however, because the Africans’ preferences for certain types of beads would change over time, and different tribes had different preferences. This seemed to be similar to the rai stones, where once new supplies of rai stones started coming in faster due to European technology, the people of Yap began wisely valuing old ones more than new ones. Essentially, the west African tastes seemed to change based on aesthetics/fashion and on scarcity. This, however, also gave that form of money a low score for fungibility, which reduced its reliability as money even for the pastoral west Africans who were using them.

Like rai stones ultimately, trade beads couldn’t maintain their high stock-to-flow ratio in the face of technological progress, and therefore eventually were displaced as money.

Japanese Invasion Money

Although its not a commodity money, the Japanese Empire used the same tactic on southeast Asians as the Europeans did on Africans.

During World War II, when the Japanese Empire invaded regions throughout Asia, they would confiscate hard currency from the locals and issue their own paper currency in its place, which is referred to as “invasion money“. These conquered peoples would be forced to save and use a currency that had no backing and ultimately lost all of its value over time, and this was a way for Japan to extract their savings while maintaining a temporary unit of account in those regions.

To a less extreme extent, this is what happens throughout many developing countries today; people constantly save in their local currency that, every generation or so, gets dramatically debased.

Other Types of Commodity Money

Emil Sandstedt’s book, Money Dethroned: A Historical Journey, catalogs the various types of money used over the past thousand years or so. The book often references the writings of Ibn Battuta, the 14th century Moroccan explorer across multiple continents, who may have been the furthest traveler of pre-modern times.

Central Asians at the time of Battuta, as a nomadic culture, used livestock as money. The unit of account was a sheep, and larger types of livestock would be worth a certain multiple of sheep. As they settled into towns, however, the storage costs of livestock became too high. They eat a lot, they need space, and they’re messy.

Russians had a history of using furs as a monetary good. There are even referenced instances of using a bank-like entity that would hold furs and issue paper claims against them. Parts of the American frontier later turned to furs as money for brief periods of time as well.

Seashells were used by a few different regions as money, and in some sense were like gold and beads in the sense that they were for both money and fashion.

In addition to beads, certain regions in Africa used fine fabric as money. Sometimes it wasn’t even cut into usable shapes or meant to ever be worn; it would be held and exchanged purely for its monetary value as a salable good that could be stored for quite a while.

Another great example is the idea of using blocks of high-quality Parmesan cheese as bank collateral. Since Parmesan cheese requires 18-36 months to mature, and is relatively expensive per unit of weight in block form, niche banks in Italy are able to accept it as collateral, as a form of attractive commodity money:

MONTECAVOLO, ITALY (Bloomberg News) — The vaults of the regional bank Credito Emiliano hold a pungent gold prized by gourmands around the world — 17,000 tons of parmesan cheese.

The bank accepts parmesan as collateral for loans, helping it to keep financing cheese makers in northern Italy even during the worst recession since World War II. Credito Emiliano’s two climate-controlled warehouses hold about 440,000 wheels worth €132 million, or $187.5 million.

“This mechanism is our life blood,” said Giuseppe Montanari, a cheese producer and dealer who uses the loans to buy milk. “It’s a great way to finance our expenses at convenient rates, and the bank doesn’t risk much because they can always sell the cheese.”

The Gold Standard

After thousands of years, two commodities beat all of the others in terms of maintaining their monetary attributes across multiple geographies; gold and silver. Only they were able to retain a high enough stock-to-flow ratio to serve as money, despite civilizations constantly improving their technological capabilities throughout the world over the ages.

Humans figured out how to make or acquire basically all of the beads, shells, stones, feathers, salt, furs, livestock, and industrial metals we need with our improved tools, and so we reduced their stock-to-flow ratios and they all fell out of use as money.

However, despite all of our technological progress, we still can’t reduce the stock-to-flow ratios of gold and silver by any meaningful degree, except for rare instances in which the developed world found new continents to draw from. Gold has maintained a stock-to-flow ratio averaging between 50 and 100 throughout modern history, meaning we can’t increase the existing supply by more than about 2% per year, even when the price goes up more than 10x in a decade. Silver generally has a stock-to-flow ratio of 10 to 20 or more.

Most other commodities are below 1.0 for the stock-to-flow ratio, or are very flexible. Even the other rare elements, like platinum and rhodium, have very low stock-to-flow ratios due to how rapidly they are consumed by industry.

We’ve gotten better at mining gold with new technologies, but it’s inherently rare and we’ve already tapped into the “easy” surface deposits. Only the deep and hard-to-reach deposits remain, which acts like an ongoing difficulty adjustment against our technological progress. One day we could eventually break this cycle with drone-based asteroid mining or ocean floor mining or something crazy like that, but until that day (if it ever comes), gold retains its high stock-to-flow ratio. Those environments are so inhospitable that the expense to acquire gold there would likely be extraordinarily high.

Basically, whenever any commodity money came into contact with gold and silver as money, it was always gold and silver that won. Between those two finalists, gold eventually beat silver for more monetary use-cases, particularly in the 19th century.

Improvements in communication and custody services eventually led to the abstraction of gold. People could deposit their gold into banks and receive paper credit representing redeemable claims on that gold. Banks, knowing that not everyone would redeem their gold at once, went ahead and issued more claims than the gold they held, beginning the practice of fractional reserve banking. The banking system then consolidated into central banking over time in various countries, with nationwide slips of paper representing a claim to a certain amount of gold.

Barry Eichengreen’s explanation for why gold beat silver, in his book Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System, is that the gold standard won out over the bimetallic standard mostly by accident. In 1717, England’s Master of the Mint (who was none other than Sir Isaac Newton himself) set the official ratio of gold and silver as it relates to money, and according to Eichengreen he set silver too low compared to gold. As a result, most silver coins went out of circulation (as they were hoarded rather than spent, as per Gresham’s law).

Then, with the UK rising to dominance as the strongest empire of the era, the network effect of the gold standard, rather than the silver standard, spread around the world, with the vast majority of countries putting their currencies in a gold standard. Countries that stuck to the silver standard for too long, like India and China, saw their currency weaken as demand for the metal dropped in North America and Europe, resulting in negative economic consequences.

On the other hand, Saifadean Ammous, in his book The Bitcoin Standard, focuses on the improved divisibility of gold due to banking technology. As previously mentioned, gold scores equal or higher than silver in most of the attributes of money, except for divisibility. Silver is better than gold for divisibility, which made silver the more “day to day” money for thousands of years while gold was best left for kings and merchants to keep in their vaults or use as ornamentation, which are stores and displays of value respectively.

However, the technology of paper banknotes in various denominations backed by gold improved gold’s divisibility. And then, in addition to exchanging paper, we could eventually “send” money over telecommunications lines to other parts of the world, using banks and their ledgers as custodial intermediaries. This was the gold standard- the backing of paper currencies and financial communication systems with gold. There was less reason to use silver at that point, with gold being the much scarcer metal, and now basically just as divisible and even more portable thanks to the paper/telco abstraction.

I think there is an element of truth in both explanations, although I consider the explanation of Ammous to be more complete, starting with a deeper axiom regarding the nature of money itself. Banknotes made gold more divisible and thus the harder money won out over time, but network effects from political decisions can impact the timing of these sorts of changes.

Central banks around the world still hold gold in their vaults, and many of them still buy more gold each year to this day as part of their foreign-exchange reserves. It’s classified as a tier one asset in the global banking system, under modern banking regulations. Thus, although government-issued currency is no longer backed by a certain amount of gold, it remains an indirect and important piece of the global monetary system as a reserve asset. There is so far no better naturally-occurring commodity to replace it.

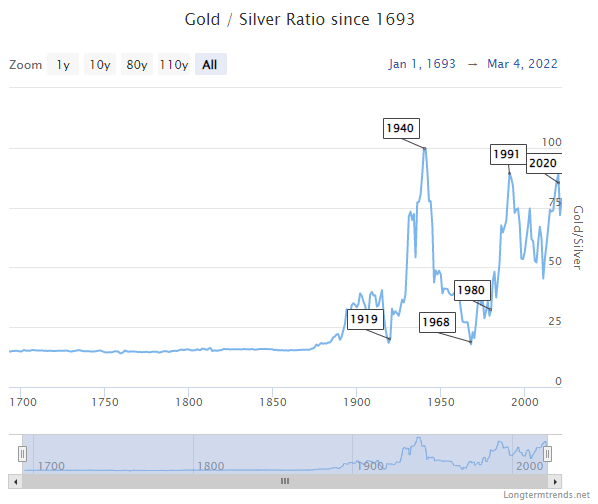

Gold used to trade at a 10x to 20x multiple of silver’s value for thousands of years in multiple different geographies. Over the past century, however, the gold-to-silver price ratio has averaged over 50x. Silver seems to have structurally lost a lot of its historical monetary premium relative to gold over the past century.

Longtermtrends.net

The next article in this series will delve into the rise of fiat currencies.

Be the first to comment