Wachiwit/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

I remember when I was learning how to fly many, many, many years ago, my flight instructor told me that the human eye is designed to spot movement. We’re attracted to things moving a great distance in a short amount of time. He then started talking about the evolutionary reasons for this, hunter gatherer, hunt blah blah blah and I fell back into my bored stupor. The point that we’re attracted to stuff that moves quickly stayed with me, though, and that might be part of the reason I’ve been thinking about Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX) yet again.

The stock has certainly moved very far, very fast, and that’s put it back on my radar. I’ve written about the company on two occasions in the past. On the first occasion, I pored over global demographic and economic data and determined that the size of Netflix’s potential market was about 365 million households, in an article with the incredibly original title “The Size of Netflix’s Potential Market is about 365 Million.” Subsequent to that, I wrote a piece where I suggested assumptions embedded in the price weren’t as optimistic as they at first appeared, and for that reason I wrote a deep out of the money put on the stock. I hope I’m not spoiling the surprise, but the put expired worthless, so I made a relatively easy $2,900 on that low risk trade. So, I initially had very positive feelings about the investment. Now that Netflix is apparently a “value” stock, I want to write about it again, because when it comes to investing, I like nothing better than a stock that’s quickly shifted from “darling to dog”, because in my experience, the crowd overdoes it on the way up, as they overdo it on the way down. Today I want to work out whether or not it makes sense to finally pull the trigger and buy this leviathan of the streaming space.

To Recap

It may come as a shock to my regular readers, but I sometimes want to refrain from being needlessly repetitive. With that written, my first piece on Netflix went into exhaustive detail about why their subscriber base is about 365 million households max. If you want to delve deeper into this, I would recommend my previous work on this name. For this article, I’m going to take that figure as an upper bound for the company. I’m then going to try to construct a pro forma analysis about future cash flows based on this assumption. I’ll get at what the company will look like if it ever reaches 365 million subscribers.

Before getting into all of that, though, I feel a need to offer some commentary on my impressions of the business.

The Ever Changing Definition of the Word “View”

As I round the 55 year mark, I find the world an increasingly perplexing place, as the definitions of various words change around me. One such change is the definition of the word “view.” As recently as 2018, Netflix counted anyone watching more than 70% of a show or movie a “view.” In early 2020, things changed quite dramatically. At that point, Netflix chose to count a “view” if a subscriber “chose to watch and did watch 2 minutes of a title.”

Two…minutes. This is troublesome in my estimation, and it prompted me to wonder why the company changed this metric. I tried to answer this question by looking at the release dates of various Netflix properties, and I’ve presented the results in a handy table for your enjoyment and edification below. Given the firehose of content coming out of this company, this is obviously not an exhaustive list, but it’s my best effort at tracking the history of the firm’s most popular or most significant content. I’d be happy to edit the table if you’d like to point out if I missed a property that generated massive, uh, “viewership.”

|

Year |

Significant Properties |

|

2021 |

Sex/Life Squid Game |

|

2020 |

Bridgerton Spenser Confidential The Old Guard Tiger King Queen’s Gambit |

|

2019 |

6 Underground Murder Mystery The Witcher |

|

2018 |

Bird Box |

|

2017 |

American Vandal Ozark Dark Godless Mindhunter Manhunt: Unabomber Big Mouth Black Mirror |

|

2016 |

Stranger Things The Crown |

|

2015 |

Marvel’s Jessica Jones Narcos Chef’s Table Marvel’s Daredevil Master of None |

|

Pre-2015 |

Black Mirror (Channel 4) Orange Is the New Black House of Cards Bo Jack Horseman |

Given that the company is so guarded about statistics, and thus doesn’t release the wealth of data it has on what’s being watched and for how long, I have no way of proving this, but I’m going to climb out on a limb and make a suggestion. I think the company changed metrics because their rate of producing very popular blockbusters has slowed. In my, admittedly subjective, opinion, the company produced much more truly original, often brilliant content before 2019, and seems to have lost its stride since. This should be expected by the nature of art. Fame and popularity is “hit and miss.” This happened to Rembrandt and Caravaggio, it’s going to happen to Netflix.

In my view, this is why Netflix decided to change the definition of “view”, and it’s why subscriber growth is slowing. The fact is that there are very many, very talented people trying to work out what various audiences will watch, and the evidence seems to be that no one has unlocked the secret yet, including Netflix. For instance, for every “Ozark”, there is a “Marco Polo.” This doesn’t mean the company can’t regain its “mojo”, but I think it does suggest that we should apply a deeper discount to future cash flows here than we would to a more predictable business.

I’m Too Dumb To Keep It Complicated

Some people who are far smarter, are far more curious, and far more willing to debate such things than me might argue about the size of the annuity associated with a two tier model.

It may be the case that Netflix could attract far more subscribers if they gave people the choice to pay less and accept advertising. Of course, this assumes that there’s a large untapped audience that would be comfortable with a Netflix subscription, but just can’t swing the enormous monthly cost. It’s a variant of an argument that I’ve heard for years: there’s hope in the Emerging Markets. As someone who lived in Emerging Markets for a few years myself, I’ve always been more skeptical than most about the argument, but that’s not really the point.

I’m not smart enough to work out how much marginal revenue the company can extract from people who are not willing to pay a subscription service, but would tolerate ads for the opportunity to watch “Man vs. Bee” or similar. I’m assuming an upper limit on households, and don’t see that changing anytime soon. Fully 42% of the world’s households are in China, India, and Indonesia, and I wrote about the challenges of reaching those three markets previously.

So I’m going to take a much simpler path. I’m going to assume that the company continues to grow at historical rates until it hits its 365 million upper bound. I’m making this assumption about growth in spite of my skepticism about its capacity to continue to crank out blockbusters at the rate it did previously. Under this fairly optimistic forecast, the company will reach its limit in about 3.3 years. Once the company reaches that maximum subscription number, I don’t foresee growth continuing, as a combination of churn, and competition will slow growth to nil. There are only so many households, and once you reach maximum penetration, the age of high growth is over.

Other Assumptions/Supportive Facts

-

In 2019, the company managed to generate ~$120 per subscriber. By 2021, this figure had jumped to just under $134. I’m going to assume that the recent slowdown in subscriber growth suggests that $134 per subscriber is an upper limit for the firm. Thus, my revenue forecasts will be based on this figure.

-

The company dropped its per user content spend from $83.29 in 2019 to $79.80 in 2021. I’m going to assume that the company continues to grow content spend at the same rate (8.4%) as it did between 2019-2022 in order to attract these 143 million potential subscribers not yet signed up.

-

I’m going to further assume a constant spend on new content of ~$24.4 billion once the total maximum of 365 million potential subscribers have been reached, in order to maintain subscriptions.

-

I’m going to assume the company continues to grow operating margin and net income margin until they hit 23%, and 20% respectively.

-

To make comparisons easier, I’m going to assume a continued share count of 444,273,850.

-

I’m applying a discount rate of 15% to these future cash flows, per the section above.

Findings

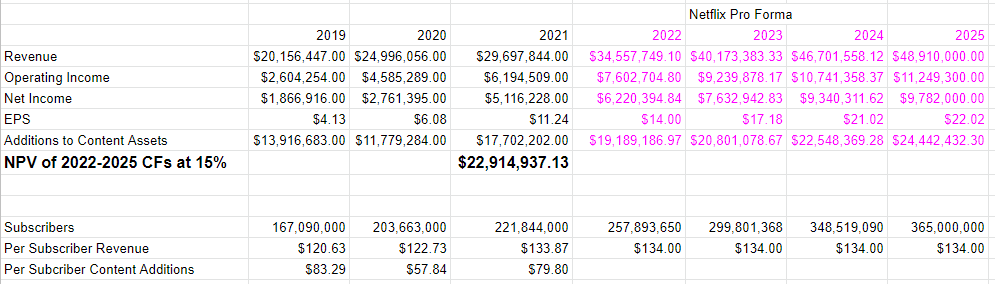

At 365 million households, and $134 per subscriber, the company’s revenue will hit just under $49 billion. The net income discounted by 15% over the period works out to just under $23 billion. While the company achieves nearly $49 billion in revenue, they will need to continue to spend just under half of that figure on new content in order to attract viewers. Additionally, we should remember that this 365 million figure is the total market, and in a world with Amazon Prime, for instance, it’s unlikely that Netflix will ever achieve it. In order to stay in this fight, though, Netflix is doomed to continue to need to generate more and more content, and there’s no guarantee that they’ll create another “Stranger Things” or pick up another “Black Mirror”, so the risk here is quite high in my estimation.

Forecast of Netflix’s Revenue to 365 Million Subscribers (Netflix public filings, author calculations)

Conclusion

Years ago I suggested that Netflix is on a content creation treadmill and nothing in the intervening years has changed my mind on that. Netflix attracts subscribers by producing new and original, great, content. This is troublesome because user tastes are fickle, and, as “Marco Polo” demonstrated, it’s not necessarily the case that more expensive content wins. For instance, my favourite piece of content at the moment is this glimpse into elephant drama, because it reminds me of growing up with my kid brother. In spite of the fact that spending doesn’t equal success, the company is obliged to continue to do so. The wheels sort of fall off the wagon when the company “cuts back on overall spending.” To use myself as an example, I’m currently powering through Hayao Miyazaki’s catalog on Netflix, but once I’m done, I may drop my subscription unless Netflix gives me some new sugar to ingest. I may be eccentric, and my taste may not be your taste (you may be more into watching Rowan Atkinson chase a bee around, for instance), but the general point is solid, I think. Consumers continue to consume as long as you provide them attractive new content to consume. Once that new content dries up, or loses quality, consumers’ propensity to consume also dries up.

Allow me to belabour this point by comparing Netflix to another recent Wall Street darling, Apple. For its many faults, there’s a good chance that one household can purchase multiple Apple products, and not the other way around. In addition, Apple itself doesn’t need to do the equivalent of producing a hit television series to bring you back for more. This has always been Netflix’s strategic Achilles heel, and no innovative revenue model is going to disguise that fact. The company needs to spend at a very prodigious rate in order to keep attracting an audience that has a great deal of choice when it comes to entertainment products. For that reason, I would recommend investing your hard earned investment capital elsewhere.

Be the first to comment