EmirMemedovski/E+ via Getty Images

Originally posted on April 1, 2022

It’s the first Friday of the new month, which means it’s time for another jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This month, unlike some in recent memory, was fairly uneventful. The headline unemployment rate ticked down to 3.6 percent, just a tad higher than the 3.5 percent rate in February 2020, right before the pandemic hit. That 3.5 percent, in turn, was the lowest level in more than 50 years. The payroll gains number, which economists tend to focus on more closely than the unemployment rate, was 431,000, a bit lower than expected but still healthy in relation to historical norms.

The labor market has been something of a mystery to economists recently. Anecdotal stories abound of positions going unfilled, with would-be employers devising all manner of carrots to entice new hires. Headlines like “The Great Resignation” suggest that a not insignificant percentage of the US population is finding better things to do with its time than showing up for a 9-5 stint. If these headlines are true (as opposed to the default assumption for everything these days of “just trying to generate more clicks”), then what are the implications for wage growth, and thus inflation more broadly?

Hot Market? No Worries!

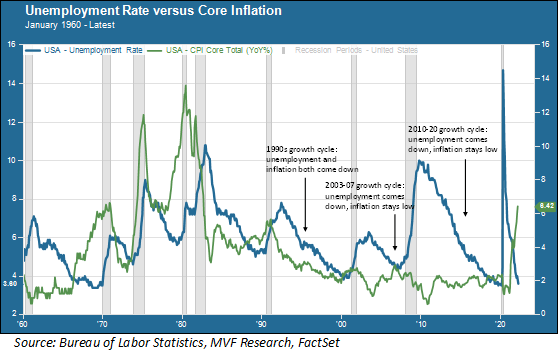

That question about the implications of a hot jobs market for inflation is important, because it is perhaps the biggest question mark in the Fed’s fairly benign assessment of the short-term environment. In the press conference following the FOMC meeting a couple weeks ago, Fed chair Powell opined that the unemployment rate would probably trend down to that pre-pandemic level of 3.5 percent, stay there for two to three years, and meanwhile inflation would trickle down from the current near-eight percent to the Fed’s two percent target. Is that a reasonable assessment of things or Panglossian wishful thinking? Let’s look at the long-term relationship between jobs and inflation, going back to 1960.

Unemployment Rate Vs. Core Inflation (January 1960 To Latest) (Author)

Looking at the above chart, it is perhaps not hard to see from where the Fed might draw its optimism that a hot labor market can coincide with subdued inflation. During the 1990s growth cycle that is, in fact, what happened: core inflation (the green trend line in the chart) fell from about five percent to two percent, while unemployment (the blue line) also went down from around eight percent after the 1990-91 recession to four percent. In the next two growth cycles, inflation stayed reasonably well-contained; this was most noticeable in the period following the Great Recession when unemployment fell from a peak of ten percent to that 50-year low of 3.5 percent. Contrary to all those economics textbooks from the 1970s and 1980s with their Phillips Curve dogma of low unemployment = high inflation, the more recent cycles suggest that the two variables do not, in fact, have to be at odds with each other.

Structurally, Things Have Changed

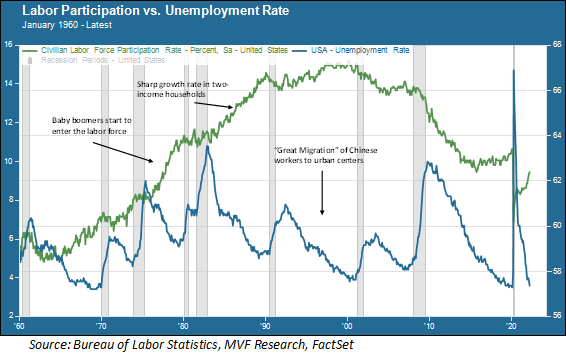

There are some other considerations that should give one pause, however, from banking too confidently on the recent growth cycle trends, and these have to do with longer-term structural issues in the jobs market. The chart below shows the same unemployment rate as the previous chart, this time compared to the labor participation rate.

Labor Participation Vs. Unemployment Rate (1960 To Latest) (Author)

This long-term view of the labor market tells three important stories, all of which were extremely favorable to the relationship between labor, wages and prices in the US. First, the initial wave of workers from the baby boom generation started coming in to the labor force in the 1970s. You can see from the above chart how this caused the labor force participation rate to rise. Alongside this massive inflow of new workers came a second trend; the rise of the two-income household as more women entered the market as full-time employees. This trend accelerated in the 1980s before levelling out in the 1990s.

Then, in the 1990s, a third trend emerged which, while not having a direct impact on the US labor force participation rate, did have the effect of allowing the unemployment rate to stay low without overheating and pushing up prices. This was the “Great Migration” of young Chinese job seekers from their rural provinces to the cities where massive manufacturing infrastructure was being created to produce the Chinese economic miracle of the late 1990s and first decade of the 21st century. In the US and elsewhere in the developed world, companies decamped from their domestic production sites to tap into this new supply of labor.

In total, then, three major global demographic phenomena all worked to the benefit of both the labor market and low inflation. All of those three trends have come and gone; there are virtually no more incremental benefits to be gained by any of them. From a global perspective, the change in the supply and demand dynamics of the labor market will, all else being equal, contribute to more pressure on wage growth, which in turn can feed into more demand-side upside pressure on prices.

This does not necessarily mean that stagflation is the only plausible economic scenario. It is entirely possible that some of the major technology innovations that have been bubbling up over the past twenty years or so will show up in the form of productivity gains. This happened in the 1990s, when technology that had been around since at least the 1970s started to visibly manifest in productivity numbers. Productivity is the key to long-term growth. If Jay Powell’s optimistic assessment of the relationship between labor and inflation is to play out, it would be nice to have that productivity show up sooner rather than later.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment