MistikaS/E+ via Getty Images

The ECB will hope and pray that inflation is indeed a temporary problem, as its room for maneuver is considerably more restricted when compared to the Fed.

There are good reasons for assuming the ECB won’t join the aggressive tightening that the Fed is embarking on:

- Economic conditions are likely to worsen in Europe due to the larger impact of the war in Ukraine.

- Much of Europe is scrambling for energy to keep the lights on in the winter.

- The eurozone is plagued by nasty debt dynamics.

- Inflation is actually helpful in defusing these debt dynamics.

War impact

There are several reasons why the war is having a bigger impact on European economies, compared to the U.S.:

- Europe in general, and in particular Germany but also eastern Europe, had more economic ties with both Russia and Ukraine, hence the boycotts and collapse of the Ukrainian (and to a lesser extent Russian) economy is having a more significant impact.

- Many European countries, notably Poland, have seen a huge influx of refugees from Ukraine.

- Multiple European countries, most notably Germany, are increasing defense spending in order to shore up security.

It’s arguable that the increased defense spending and influx of refugees is actually a net positive for the economies so there are some mitigating forces. However, the most dramatic impact is surely in the field of energy.

Energy

Europe is scrambling for energy, from The Economist:

Germany has reversed plans to retire more than one-fifth of its coal-fired power stations this year. Austria, Britain, France and the Netherlands have said they may either delay closures of, or reopen, coal plants. Some of the seven European nuclear plants that are due to be shut by the end of winter may also be kept operating a bit longer. Yet even if all of this is done, gas will probably continue to set electricity prices.

All these actions are by no means a guarantee that gas doesn’t have to be rationed in the winter. Russia is putting the squeeze on, preventing the summer build-up of gas storage to the target level of 80% by October.

The build-up could be stuck at two-thirds, or even 60% if the (supposed) scheduled maintenance of Nordstream 1 in July won’t restart, and the continent is also hampered by the shut down of the Freeport gas-liquefaction facility in Texas due to a fire.

One might wonder why Germany doesn’t restart the three nuclear power plants it shut at the end of last year and gives the remaining three nuclear power plants, scheduled to stop functioning at the end of the year, an extended life.

Well, it turns out that the electricity generated from these would only replace a small fraction of Russian gas (gas and electricity are poor substitutes) and there is a barrage of bureaucratic, practical and political hurdles to overcome.

The nuclear problem is actually bigger in France, where it is good for about 70% of French electricity generation but plants are running at less than half capacity due to maintenance requirements.

Debt dynamics

The thing about the eurozone is that you can’t really have a monetary union without a fiscal union, where you have a big central budget that automatically redistributes money from booming parts to slumping parts (like the Federal budget does in the U.S.).

This creates a situation in which divergence in economic situations has no natural break and tends to become stuck in a self-reinforcing feedback loop (or actually several of these).

Other fundamental problems are that you have one monetary policy fitting nobody, and the country’s sovereign debt is denominated in a currency (the euro) that they can’t print.

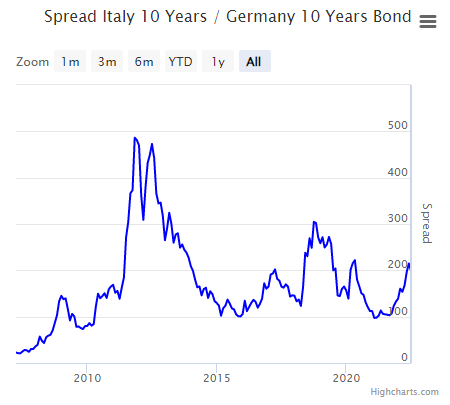

We have seen this film before about ten years ago when Southern European countries (Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal, but also Ireland) buckled as investors were fleeing their sovereign bonds, causing a chain reaction and self-reinforcing feedback loops:

- Spreads with German 10-year yields spiked up and solvency became problematic and these countries, apart from Italy, needed a bailout.

- Banks from these countries suffered heavy losses from their large holdings of sovereign debt, creating a doom loop where they would need support, further worsening their country’s fiscal sustainability.

- And another doom loop runs from worsening bank balances to reduced lending, worsening the economy given how Europe in general depends more on bank lending compared to the US which finances more investment through the capital markets.

- And yet another doom loop was created as capital can freely move within the eurozone and prospects of a possible exit from the eurozone caused a capital flight from these countries (most notably Greece), producing a sharp monetary contraction and banking crisis, further worsening the situation and without mitigating currency depreciation.

The rot was stopped a decade ago by a brilliant move from the then ECB president Mario Draghi, who argued that he would do “whatever it takes” to save the eurozone, surprising even his colleagues as no details were worked out at the time.

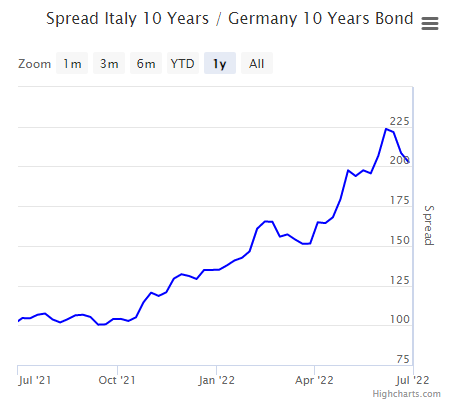

There are signs of similar stress developing today and that’s not surprising, given the economic background. Debt/GDP levels have risen substantially compared to a decade ago and the emergence of inflation is complicating the way forward for the ECB.

Inflation fighting requires tightening policy while keeping sovereign bond spreads in check requires the ECB to buy possibly large quantities of misbehaving bonds, which amounts to monetary expansion.

The genius of the Draghi trick was that it worked without actual bond-buying (although that occurred years later), but created the firm expectation in the market that the ECB would not hesitate and do so in whatever quantities required should circumstance call for such action.

It is doubtful whether this trick can be repeated, given the changed circumstances with the ECB also having to fight inflation. The one saving grace is that today it’s less controversial to buy just Italian or Greek bonds, rather than across-the-board eurozone bonds pro-rata to their national capital stakes in the ECB.

It has to be said that the new ECB president Christine Lagarde hasn’t been nearly as decisive as her predecessor, but ultimately the all-important Italian-German bond spread has come down a bit while investors await the exact mechanism with which the ECB will preserve eurozone integrity:

World Government Bonds

An Italian debt crisis isn’t imminent as the average time to maturity of Italian bonds is close to 8 years and the average interest rate on its debt is 2.4%. So even a dramatic rise in Italian yields will have a pretty muted impact on debt dynamics in the short to medium time unless markets start to panic. One might also want to put it into perspective:

World Government Bonds

We are still far away from the spreads of a decade ago although the steep rises in several periods indicate that one can quickly get there should the situation be mishandled.

Inflation

However, the eurozone debt dynamics are complex enough to compromise the ECBs ability to fight inflation. That’s why we haven’t seen the type of aggressive monetary tightening that the Fed has embarked upon, and the main reason why we see continued euro weakness.

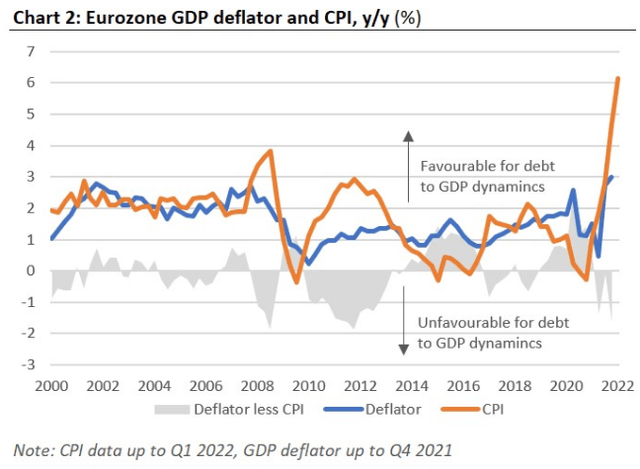

In theory, inflation is also helpful in defusing the ugly debt dynamics in the eurozone as it inflates the debt away. However, this is much less the case when it’s the CPI rising much more than the GDP deflator:

This scenario is likely to lead to subsidies to relieve the pressure of consumers which put further upward pressure on prices and widens the government deficit.

But still, nominal growth greatly exceeding nominal interest rates is a tailwind in improving the debt/GDP ratio, unless the economy enters a severe recession reducing nominal growth considerably despite inflation.

U.S. rates

A counterargument against a softer euro is that investors are now so convinced that the Fed has woken up and is now equal to the threat of inflation that market worries are now visibly shifting from higher rates towards a recession risk.

This is already visible in U.S. bond yields, which have shifted downwards considerably with the 10-year Treasuries well below 3% again.

If this trend continues it could end up shifting EUR/USD. We’re not there yet, and the 2.85% on the U.S. 10-year Treasuries is still more than double the yield on the 10-year German bund.

In any case, even if that happens it will likely be temporary as the U.S. will also be the first to get out of a recession.

In the meantime, investors could sell or short the long euro Invesco CurrencyShares Euro Trust ETF (FXE) FXE or buy the short euro ProShares UltraShort Euro ETF (EUO).

Conclusion

The ECB has several motives for not tightening as aggressively as the Fed:

- Potentially nasty debt dynamics

- A bigger impact on European economies from the war in Ukraine

- Inflation helps to reduce debt/GDP ratios.

All this is likely to keep pressure on EUR/USD, except if bond yields keep tumbling in the U.S., which might start to soften the dollar at some point.

Be the first to comment