Chalabala/iStock via Getty Images

Introduction

Back in 2018, I wrote here that “The Camel’s Nose is in the Tent,” describing how yield curve inversions, once they start, usually – but not always – spread out along the curve. The title refers to an Arab proverb. What it means is, once the camel’s nose is in the tent, the rest of the camel is likely to soon follow, with bad consequences for the people in the tent.

There has been surprisingly little commentary on portions of the US Treasury yield curve inverting in the past week. This began with inversions at the 7 to 10 year and 20 to 30 year maturities, but has since spreads further into the intermediate and shorter maturity range.

Here’s a look at the yield curve snapshot from Stockcharts.com:

Note that this graph omits the 3 year maturity, which 3x in the past 10 days, including yesterday, closed at a higher yield than the 5 year, and which I’ll discuss at some length below.

Most of the commentary you have read in the past probably boils down to an assertion that yield curve inversions are bad (generally, they are) and that a recession is now likely in the next 12 to 24 months (maybe). But let’s go to the graphs, and then step back a second for some consideration.

A look at the history

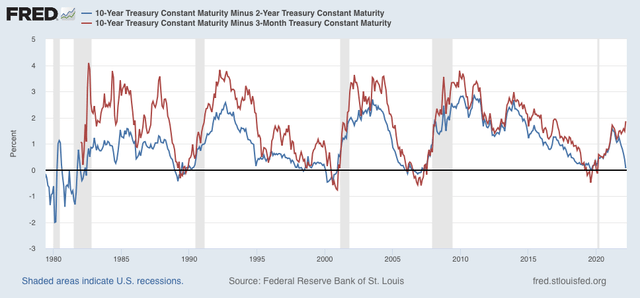

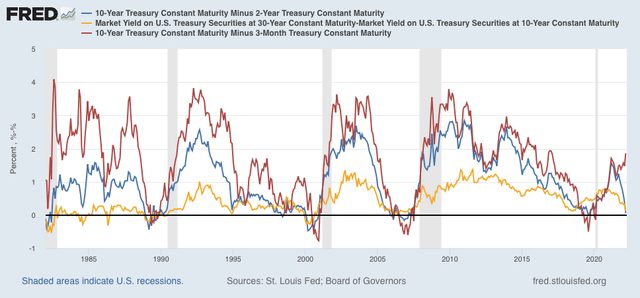

Here are the most well-known spreads, those between 2 and 10 year Treasuries (Blue), and 3 month and 10 year Treasuries (Red), going back 40 years:

These two metrics have nearly impeccable records. Both inverted at least briefly within 24 months of every recession in the past 40+ years, although the former only inverted for 3 days in August 2019 (yes, the pandemic brought about the 2020 recession, and we’ll never know for sure whether there would have been one absent Covid), and it also gave a false positive with an inversion in June and July 1998, almost 3 years before the 2001 recession. Meanwhile the latter has no false negatives or positives, although it had a near miss on a false positive by inverting in January and February 2006, nearly 2 years before the Great Recession.

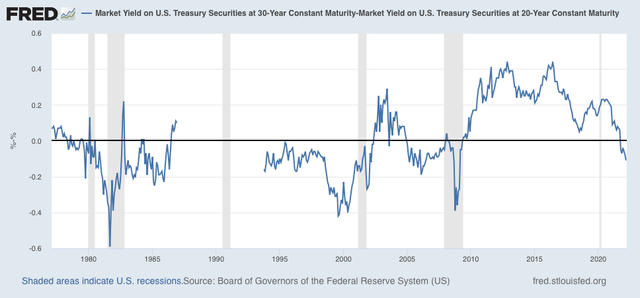

On the other hand, some inversions give many false signals. For example, here is the 20 to 30 year spread, one of the two which first inverted nearly 2 weeks ago:

Plenty of false positives here!

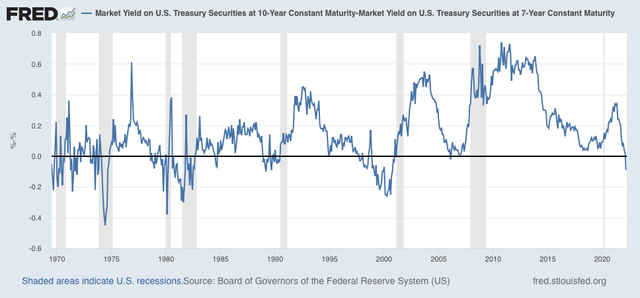

And here is the 7 to 10 year spread, which also inverted nearly 2 weeks ago:

There’s a complete miss in 2019, a failure to invert except for a few days in 2006, and false positives in 1971, 1984, 1995, and 1998.

BUT…

Implications

The applicability of the idiom that “the camel’s nose is in the tent” to the bond market is, once several maturities have inverted, historically more often than not maturities all along the curve follow, and with that give a 12 to 24 month recession signal.

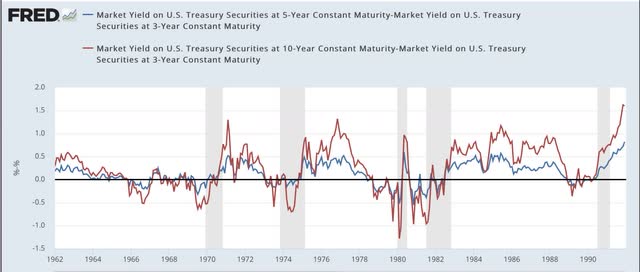

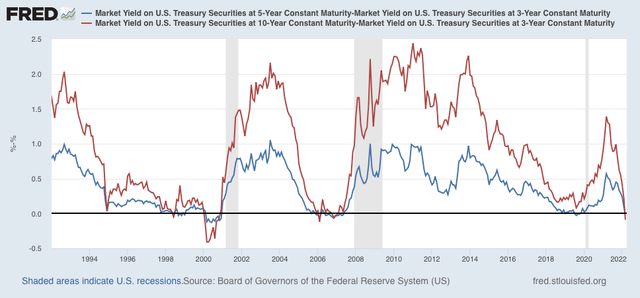

And indeed, in the last week the 10 to 3 year and 5 to 3 year spreads have also inverted, as shown in the below 2 graphs giving their entire 40 year+ history:

These two spreads have a better record, although both gave false positives throughout the late 1960s, 1971, and 1998, and the 10 minus 3 year spread did not invert in 2019 (arguably a false negative). But since the early 1970s, in other words, for the past 50 years, when these two have inverted, the more well-know 10 minus 2 year spread has shortly followed.

That appears likely to be happening again, as yesterday the 10 minus 2 year spread was only .06%, as shown on the first graph above.

BUT FURTHER, let’s discuss 1998.

Here is a graph of the 2 vs. 10 year, 3 month vs. 10 year, and 10 vs. 30 year spreads over the last 40 years:

Several times – at the end of 1994 and the beginning of 1998 – an inversion only happened for one day or even only intraday. Not only did they not signal an oncoming recession but a reversal to a normal spread happened almost immediately. In other words, bond traders have agency, and as a whole (i.e., “the market”) might decide that the move has gone on long enough. In short, a one-day inversion over a limited portion of the bond yield curve, while more often than not heralding a full-on inversion and bad consequences to come, is by no means dispositive.

Further, in 1998, not all spreads inverted at the same time. While the 2 vs. 10 year inverted, the 3 month vs. 10 year and 10 vs. 30 year did not. For there to be a true signal, there should be simultaneous inversions over some stretch of time – as there was in 2000.

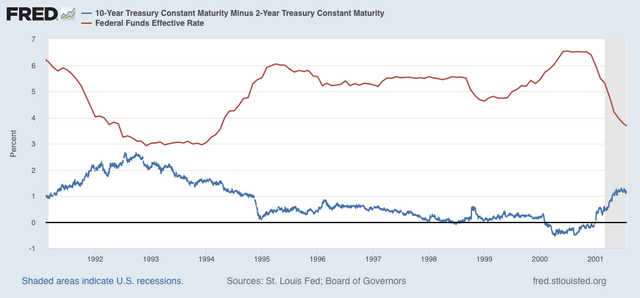

Most significantly, as in 1998, the Fed might react. Here’s a graph of the 2 vs. 10 year spread vs. the Fed funds rate during the 1990s:

Note that the Fed reacted very quickly to the Long Term Capital Management crisis in summer 1998, only several months after the inversion began, and lowered rates. No recession occurred until after the Fed resumed raising rates in the teeth of an inversion in 2000.

In other words, if you are aware of the history of an inversion, and if I am aware of the history of an inversion, and if all of the other economic and financial commentators are aware of the history of an inversion, then don’t you think the Fed and its economists might possibly discuss the possible implications of an inversion in their next meeting?

The Fed is an actor. The Fed has agency. The Fed can affect the future course of the bond market. The Fed can react to the news of a yield curve inversion if it chooses, and thereby change the future. If a widespread yield curve inversion develops now, will the Fed choose to continue to fight inflation, or to take its foot off the brake pedal?

Conclusion

Long term readers know that I was bullish on the economy since spring 2009 all the way until the end of 2018. The economy had a near miss to a recession when Covid came along in spring 2020 and finished the job. I quickly turned bullish again. Even if my suite of long leading indicators continue to deteriorate, as they have recently, the Fed and other economic actors can react to them and avoid a downturn.

But, as of now, the camel’s nose is in the tent.

Be the first to comment