Torsten Asmus/iStock via Getty Images

Whither Inflation?

The Present

The US Fed just announced CPI year over year inflation of 9.1%, the highest level reached in 40 years. This has caused the Fed to undergo a series of Fed rate hikes at an unprecedented rates, raising rates form 0.2% to 2.25% in less than 6 months.

The Prevailing Inflation Consensus

It seems like only yesterday when a large number of economists believed inflation was permanently cured. Due to the effects of globalization, growing trade and manufacturing specialization, an aging population in the developing world consuming less and less, and rapid technology increases, the demand for goods and services would decline just as robotics and technology immensely increased our ability to increase supply.

Furthermore, with the US, Europe, Japan and China bogged down in overwhelming levels of debt, growth overall would slow. Government austerity measures would imply more taxes, less spending and fewer jobs. This would be disinflationary at the least, and possibly even deflationary. The deflationists argued that this overhang would persist for years as the world paid down debt, and the smart trade was to own Treasury bonds.

Unending Inflation – The New Bogeyman

But then, in almost the blink of an eye, inflation exploded up. Just as quickly, it seems, the economic consensus has reversed. Now inflation is the new beast to be tamed at all costs. Many economists fear the governments will do too little, too late to conquer inflation, and it will become endemic, impossible to root out short of economic Armageddon.

As proof of central bank indifference or incompetence, the new inflationary consensus points to the real and continuing negative interest rates, even after the latest central bank rate hikes. True, with inflation at 9.2% (officially) in the Fed Fund rates at around 2.25%, the real cost of money in still a negative 7%.

This is the opposite of tight money, the new inflationary proponents argue. According to them, continued negative real interest rates are just adding fuel to an already explosive fire. Add in debt levels that prevent governments from tightening more, a broken-down global trading system now trending heavily towards industrial reshoring, a diminishing active labor force, and you’ve got seriously inflationary headwinds.

The Unpleasant Middleground – Stagflation

So which view is right? I tend to believe they both have valid points. The interplay of these factors will keep us in a middle range, a prolonged period lasting at least a decade in which we’re stuck with higher inflation in the 4 to 6 percent range, accompanied by languishing growth. I expect real GDP growth at less than 1% annually after inflation, and possibly negative.

Why? Well let’s look at the different forces at play, starting with demographics. The US, Eastern and Western Europe, Japan, China, Russia are all to varying degrees, fighting a population collapse, while the emerging markets more or less flip that equation.

Whereas the booming young populations of the emerging world could provide a solution through immigration, the emerging forces of nationalism and population in the developed world will prevent that from occurring until a new political consensus emerges. That will take time.

In the meantime, older populations will depress consumption just as a smaller available work force will increase wage pressures. One depresses prices, the other increases it. Both reduce profits.

Then we have the war in Ukraine. This not only severely impairs the flow of goods, energy and raw materials globally, but it also is leading to the disruption of the global monetary system and a reinvention of global trading alliances and institutions.

Those are extremely inflationary forces, but also forces that greatly diminish productivity.

And what of China’s continued attempt to battle any spread of Covid in China? In my opinion, the contagiousness of Covid variants and the ease with which outbreaks quickly spread, make this battle one of Sisyphean proportions. Since the regime in China has made the battle against Covid a matter of Chinese honor, while at the same time proselytizing against Western remedies and vaccines, the CCP leadership is unlikely to be able to bring the Chinese economy back to health any time soon. This means a diminished supply of goods from the largest exporter in the world – an inflationary trend – while at the same time reducing the demand for raw materials globally – a big deflationary force.

Technology meanwhile, is propelling us to unheard of efficiencies that are just beginning to play out in terms of increasing productivity. Normally, the global shutdown we experienced in government lockdowns under the Covid pandemic should have reduced GDP growth by high double digits. But it did not, thanks to the breakthroughs of technology, permitting surprisingly high productivity from home-bound workers.

The biggest technology breakthroughs are already upon us, in the forms of nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, and robotics. As the author Jeff Booth has masterfully described in his seminal book The Price of Tomorrow – And the Era of Abundance, these breakthroughs will begin to impact every aspect of modern economies, and usher in cost-reductions and supply increases that we find difficult to imagine. Those are extremely deflationary forces.

Which forces – deflationary or inflationary – will emerge dominant? Much of that depends on politics. According to investment legend and economic historian Ray Dalio, the world is entering a period of populism, nationalism and war.

I have lived in Germany, Italy, the US and Colombia, and I can certainly detect the stark signs of those trends in all of those countries. In the US, I think at least 2 election cycles will have to come and go before we can begin to rebuild a national consensus.

Meanwhile, I don’t see a political leadership emerging with the will to confront the problems that we face. As a consequence, we will continue our 20-year pattern of printing ourselves out of any deep recessions, while succumbing to fits of monetary tightening whenever inflation hits new highs, which it inevitably must in our increasingly zombified economy.

So in the next few months, we’ll see markets drop as the real effects of their recent tightening are felt. We’re in the midst of a relief rally bases on the hope that this is the last of the rate hikes. This will not last, I believe.

Real hardship caused by recent inflation may cause consumption to continue dropping. Businesses may see their sales drop, and price increases – tolerated to a large extent by consumers fattened by government largesse – may no longer offset that. leading to profit squeezes. Businesses tightening their payrolls would then cause increased uncertainty, exacerbating consumption hesitancy.

I have no doubt that home prices will soften, then drop sharply, as the latest rate hikes filter into long term mortgage costs.

But weak unpopular governments have greater difficulty confronting a deep recession. They often pressure central banks to inflate their economies again. and thus the cycle repeats.

I doubt we will get the deep cleansing effect of a prolonged recession. As Schumpeter described, those are painful, but necessary episodes that permit the rotting sectors of an economy to die out and new healthy sectors to emerge. The more we delay that painful treatment, the longer the recovery process will be.

Investing Safely in Stagnant Times – Hedged Steepener Bonds

Each premise on the future of inflation implies its own series of investments. Since I am convinced we are facing stagflation – comprised of low growth and inflation 2 to 3 percent higher than we’ve witnessed in the past 30 years – I’ll present one investment idea that will work for the conservative crowd that wants to make one or two investment moves a year, without constantly fussing over their portfolio returns.

(For active investors, there’s a more profitable path, but one that involves a lot of buying and selling of options, and active management. I’ve described path this in my article Milking The Cow written two years ago. )

My conservative strategy involves a combination of long term structured bond products known as steepener bonds, along with long-term option hedges, renewed each year. The strategy requires about 3 trades a year.

(Readers may wish to visit my previous article on this approach written in 2016.)

This approach makes sense if growth stagnates and inflation persists at moderately high levels of 5 to 7 percent, or if we enter a period of long term deflation.

The Nuts and Bolts of Hedged Steepeners

This strategy is admittedly complex, but it’s worth your while to wrap your brain around understanding it. Contrary to popular opinion, the KISS principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid) does not apply to investments. Something simple to understand will rarely be very profitable. Why? Cause everyone would do it, reducing its profitability. A complex investment is not necessarily profitable, but a profitable investment is almost always complex.

The hedged steepener investment involves purchasing a long-term steepener bond. These are structured products offered by large and small banks. These bonds are generally only available through bond brokers, so consult with your financial advisor if you don’t see them listed on your own broker platform.

Most steepener bonds are only backed by the good faith and credit of their issuers. So you want to make sure that those issuers – even were they to fail – would be saved from collapse by the US government. I would only recommend buying from US-based “too big to fail” banks. That is JPMorgan (JPM), Morgan Stanley (MS), Bank of America (BA), Citigroup (C), and Wells Fargo (WFC), and a few others.

The bonds typically have a period of guaranteed interest, followed by a much longer period during which the interest paid depends on the differential between long term interest rates and short term rates. Sometimes they guarantee the initial interest no matter what, other times it is subject to the broad stock indexes not plunging below a certain threshold.

Each bond is offered for a usual restricted period of time and in limited size. Minimum investments start at $1000 and max out at around $300 million.

The steepener bonds are so named because they benefit most when the difference between long and short term interest rates grows wider and the yield curve steepens.

Right now these can be bought at around 98 cents on the dollar. (You want to avoid paying more than $1.00 on a new issue of a steepener bond if the bond can be called. Unlike many other bonds, these steepener bonds quickly get called when they trade above par.)

As an example, let’s look at a recent Citigroup offering that is currently on my desk, and may have already sold out by the time you read this. If that one sells out, another similar one will soon be available.

Bonds @ 97.75

Citigroup Global Markets Holdings Inc.

C Float 07/29/2042 17330PPA1

Call 07/29/2023

Cpn pays/reset quarterly

Trade/Strike date: 07/27/2022

Settle date: 07/29/2022

10% to 2025, then

Cpn subj to:

50*(30s -2s); 10% Cap

SPX >/= 50% of initial * 50% Cushion

** 100% PPN – Subject to full faith/credit of issuer **

This is a long term bond expiring in 20 years. You’re essentially buying it at a slight discount to par, at 97.75 cents. You will get a 10 percent dividend, paid quarterly no matter what in the first 3 years, but it could be called off of you at par value.

After that period, you’ll get a payment only if the stock market has not crashed so much that SPX trades 50% below its price on July 29th. If it is below that value you get no coupon for each period during which it is below that level. If it ticks back up you start getting interest again.

So if you feel inflation will be brought under control, or that inflation will be contained in a higher 5-7% range over the next 10 to 20 years. here’s an easy way to get real return of between 5% and 3%.

Net of inflation, that’s a great return. Just buy the bond. No hedge needed. After the first three years, the bond switches from a fixed payout of 10% to one that is equal to 50 times the spread between 30 years swaps and 2 year swaps, but capped at 10%.

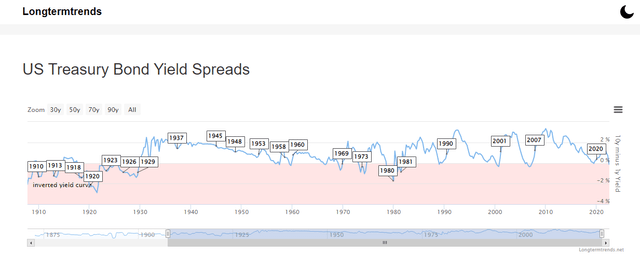

The graph below shows gives you an idea of the usual difference between the two rates over history and how many times the difference turned negative. In such cases, the steepeners would stop paying you until they the yield curve reverted to positive once again.

I could not find stats going back far for the 30 year / 2 year, so I looked at the 10 year / 1 year, which have followed a similar pattern.

Historic yield curve between 10 year and 1 year treasuries (longtermtrends)

Notice that the only prolonged period of negative yield curves was in the early years of the Federal Reserve (created in 1913). At that time, Keynesian policies did not exist and central banks did not take active measures to reflate an economy in the doldrums.

Since Keynesian policies gained favor among bankers and economists, any time the yield curve went negative, causing a recession, the Fed would quickly reverse policies, lowering short term rates once again to spur the economy once more. Yield curves then quickly went positive.

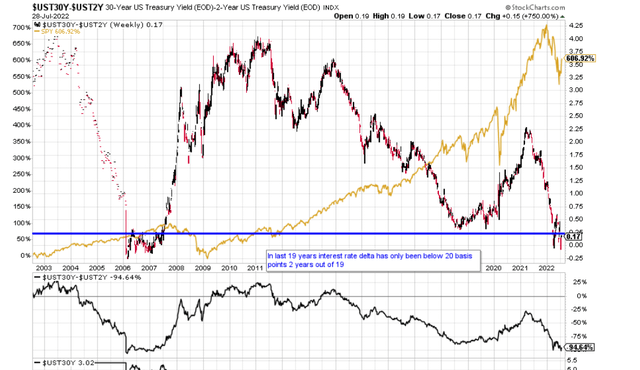

Here’s a graph of the last 19 years.

30 year vs 2 year interest rates (StockCharts)

You see that the differential (30s minus 2s ) only went negative on four occasions in the last 19 years, and each time for only a matter of 3 to 5 months. During the entire rest of the 19 years, if you’d have held a steepener with similar terms to the aforementioned Citigroup bond, you’d have comfortably earned 10%. (Of course many of those bonds did not exist back then.)

You will also notice that current yield curves are inverted. Two year interest rates (and their correlated swap values) are trading higher than 30 year rates. This would be bad if you were holding the Citigroup bond in the fourth year of its term. But for the next 3 years, that particular Citigroup bond offers you a guaranteed 10% return no matter what swap markets do.

I expect history will repeat itself. We’ll see the recession that we’re already in intensify, and the negative effects on stocks, employment and real estate will cause the Fed to reverse its policies once again. As it has historically, I think this will play out over a period of about five to eight months, max.

With this particular bond, since it pays 10% even in a stock market crash in the first 3 years, there is no need to hedge at all (except against a Citigroup default, discussed below). But many steepeners stop paying a dividend even in the initial period if major indexes drop below the stated threshold. In that case it makes sense to hedge.

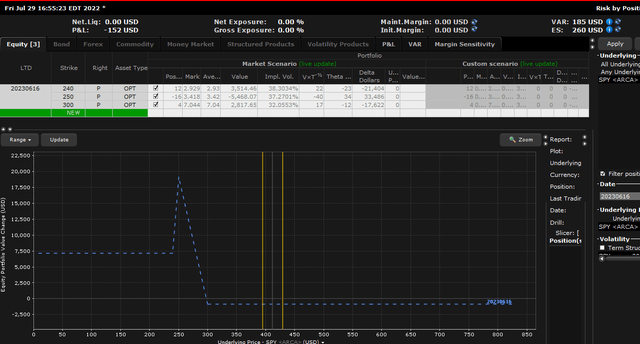

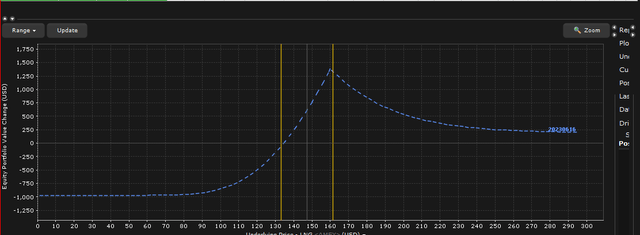

For example, a 50% drop in SPY from today’s levels implies a SPY around $205. You could initiate the following LEAP option play (a broken wing butterfly) to benefit if that occurred:

SPY hedge against 50 percent drop (StockCharts)

As you see if you’ve got $99k invested in the Citigroup steepener bond certain to yield you $9900 (short of Citigroup bankruptcy) , you could place $1000 in put options expiring in 11 months that use a broken-wing butterfly strategy. On the day of expiration, if you had put on this trade and stocks had indeed fallen by 50%, you’d have made at least $7500 and gotten your $1000 original premium back. On a lesser drop in the range of 15% to 30%, you’d make up to $19,000. This is independent of the bond dividends that you’d still be getting.

If you’re greedy (I am), you might want to put on the trade in addition to buying the Citigroup bond. Worse case? Stocks don’t drop and you’ve “only” made 8.9% on your $100k investment. Best case? Stocks drops a lot and you pocket a cash flow of 19%.

Default Risk – The Elephant in The Room

In a profound credit crisis with unforeseeable consequences (think 2008), I don’t believe any of banks mentioned above are completely safe from bankruptcy. However I do think that the likelihood of such bankruptcies is currently very low (under 1%).

More importantly, I believe the banks mentioned are such linchpins of the US financial system that they would not be permitted to fall into bankruptcy. Just as it did in 2009, I believe that the US government would again print money or use taxpayer funds to bail them out. As part of the package, their bond obligations would be honored.

But there is still a small risk that in such a crisis, the US government might choose to save depositors but allow a big bank to fail, in which case bondholders could suffer a significant loss, maybe on the order of 30%, 40% or even 50%.

I believe that an investor paying attention would have time to see such events unfolding. In the 2008 crisis, the headlines were full of discussions of crises and bailouts months before the actual collapse of Lehman Brothers.

So as any such events unfolded, I would take defensive measures. It would be very difficult to liquidate the bonds without suffering principal loss in doing so, but a hedge against bankruptcy could be established using options to hedge out most or all of the losses incurred in a bankruptcy.

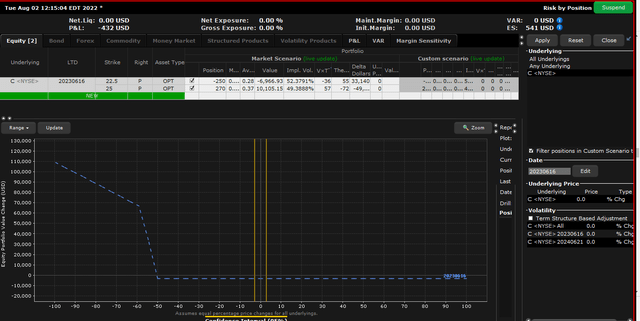

For example, right now, I would be able to establish the following option to protect 110% of the modeled $100,000 portfolio at a cost of about 3.2%. It spends about $3200 to ensure a payout of $110,000 on a Citigroup bankruptcy where the stock price goes to zero.

Citigroup hedge to jun 16 2023 (Interactive Brokers)

This hedge could be used in lieu of or in a mix with the above-mentioned hedge on SPY.

The Catch – Many Steepeners Are Callable

When purchasing steepeners, pay attention to the callability feature. In this particular case it may be called anytime at par after 1 year has elapsed. This puts a lid on how high above par the bond will ever trade.

If stocks collapse by 50% tomorrow, it’s still got a year to run paying you a guaranteed 10%. So you’d expect it to trade at a premium of 6 to 9%, but not more. As months pass and the bond gets closer to the call date, that premium would quickly drop, similar to what happens to an option.

Now let’s assume a prolonged period of stagflation, in which long term bonds are hovering around 4 to 6 percent, but you don’t have inversion of the yield curve. In that case the bond is an incredible investment. But guess what? Citigroup is highly likely to exercise the call buying it at par. Even if Citigroup had themselves hedged the bet using futures and suffered no loss (most likely), it would be profitable for them to own for their own accounts, and they would have the right to do so.

But remember, even if this happens a couple of years out, you’ve made money in the interim, and suffered no loss of principal.

What If I’m Wrong and Inflation Climbs Much Higher?

Readers beware: If you believe we’ll see persistent inflation in double digits, at greater than 9 percent, this is not the approach for you. You will lose money if that happens.

Why? Well, let’s assume that the Fed stops tightening short term rates, perhaps because it feels inflation is responding to supply constraints and not demand pressures. Maybe it opens the spigots again, fearing government insolvency. Perhaps there’s a dollar crash, as foreigners bail out of the US dollar due to international events. (I’m do not think this is a likely scenario but I’m playing the devil’s advocate.)

If inflation is judged by a majority of holders to be endemic, and running very high, then long term treasury rates will rise sharply as long term holders abandon an instrument guaranteed to lose them money each year. If inflation is thought to be permanently at 11% for example, 20-year treasuries would have to yield more than 11% to be worth holding long term.

In order to compete with newly issued treasuries of 20 years paying 11% or more, existing steepeners would have to trade at a discount, somewhere in the 10 to 20 percent range, possibly more. So if you were holding these bonds, you’d be stuck permanently losing 1 per cent each year to real inflation for the next 20 years. Or you’d want to unload them on the secondary market right away to avoid that, but you then you’d face an immediate 10 to 20 percent loss of principal. Both alternatives would be bad.

Can I Have My Cake And Eat It Too?

Wait, there might be one alternative approach, where you can have the best of both worlds. Consider buying the steepener, and locking in 10% for at least a year. Put 90% of your money in that bet.

Since you’ll make 10% of 90% of your money, that’s a 9% return on 100% of your portfolio.

Split the remaining 10% of your money between options bets on the market crashing (see above) and inflation rising even higher. If I am correct and the recession deepens and stocks correct down severely, you’ll do well on the 5% of money betting on a downturn.

But how do you find investments that make money if inflation takes off? Well, if inflation persists even after the Fed’s recent tightening, it’s because it’s supply-driven. Most likely its due to the continued high cost of fertilizers, food, energy sources like oil and natural gas, and finally rising labor costs.

I’m not sure how to play the labor angle, but for oil and gas, food and energy a few investments come to mind: think Exxon (XOM) for oil, Cheniere Energy (LNG) for natural gas, Bunge (BG) for food, and Denison Mines (DNN) and First Solar (FSLR) for “socially accepted yet financially viable” energy plays.

My own preference as to how to invest in these sectors involves long term options (LEAPS) structured in a way to avoid the usual theta decay that accompanies most options investing.

If I believed in very high persistent inflation going forward (I don’t!), I would split 5% of my portfolio over a series of option bets like the following:

Let’s say 1% of your portfolio represented $1000. You could risk losing that entirely if you are wrong, but make a likely $500 to $1500 as long as natural gas prices end the year between 10 percent lower and in a range of minus 10 percent to a positive 30 percent over the next year.

Calendar spread in LNG. Risk $1000 to make $500 – $1500 (StockCharts)

Similar plays can be done for all of the stocks mentioned. If inflation continues to rage, this means that the 5% you’ve invested in these options could boost your portfolio by 5% to 15%.

If you’re wrong and inflation does not pick up, but prices remain at current levels, these options will neither make nor lose money.

Finally, if inflation does reverse and this portion of your portfolio goes sour, you’ll have lost 5%, but done well on the remaining 95% of your portfolio.

Once a year, as these LEAP contracts expire, you’ll have to rinse and repeat the strategy.

What’s Your Maximum Risk Using Steepeners?

There’s not an easy answer to this question. It depends how you structure your hedges, and which hedges you put on.

Don’t put on any hedges? You would likely lose up to 50% of your money in a Citigroup bankruptcy. Short of bankruptcy you’d do fine, getting a nice return when everything around you is falling apart.

If you do put on the hedge, you’d make out like a bandit, but at the cost of losing 3% of your dividends if that never happened.

If you don’t hedge for accelerating inflation, and this occurs, you’d make 10% on the steepener but see those earnings evaporate due to the lowered buying power of the dollar.

Where’s Inflation Going? Your Portfolio Wants To Know.

So there you have it. Pay attention to inflation, because your portfolio will be heavily impacted if you get the equation wrong. Wouldn’t investing be so much easier if you’d just paid more attention to that boring Economics teacher? Oh well…

Be the first to comment