Introduction

Despite its technical business, Rolls Royce (OTCPK:RYCEF) is a well-known name. By way of introduction, it can be described as a provider of power sources for a variety of industries, most notably the aerospace industry. The company divides its business into four segments:

- Civil Aerospace manufactures engines for the aerospace industry.

- Power Systems manufactures engines/propulsion systems for a variety of industries, including oil & gas among others.

- Defense manufactures engines/power systems to service government contracts.

- ITP Aero provides engine design and maintenance services for other manufacturers and airlines.

My discussion will be focused on the Civil Aerospace segment because its Rolls Royce’s largest segment and primary driver of value (and its stock price).

Thesis

Rolls Royce has solidified a niche position in an extremely defensible industry supported by multi-decade tailwinds. The conflation of a complex business model and even more complex financial model has resulted in the company’s cash flow generating potential being significantly misunderstood by investors. A “perfect storm” of issues, including a forced accounting change, issues with its Trent 1000 engines and the impact of the coronavirus, has resulted in the stock trading at decade-low levels. As the effects of coronavirus subside and the company enters a highly cash-generative phase in its investment cycle, its stock should re-rate to levels more than double its current price.

Defensible Industry

There are four major players in the industry: General Electric (GE), Pratt and Whitney (subsidiary of Raytheon – merged with United Technologies this month to create Raytheon Technologies (RTX)), CFM International (JV between GE Aviation and Safran (SAFRF), a French company) and Rolls Royce.

Over the past several decades, there have been no serious entrants into the industry, the reasons being the extremely high investment costs required to develop engines and the reputational factor inherent in engine purchases (i.e., a new entrant will find it very hard to compete with GE’s brand name). To give a sense of the investment required, a ~2,000 engine program will cost anywhere from $4-5 billion and 10-20 years to develop. During this period, the engine manufacturer is receiving no revenues. For this reason, many of the incumbent players compete in this industry by way of joint ventures (for example, the development of LEAP Engines by GE and Safran) or as subsidiaries of larger industrial companies. Rolls Royce is the only “pure-play” engine manufacturer.

The narrow-body business (small regional jets) is dominated by GE, Safran and Pratt and Whitney (Rolls Royce exited the industry in 2012 after selling its stake in International Aero Engines (IAE) to Pratt and Whitney). Rolls Royce currently competes in the wide-body business (large 2-aisle airplanes) in a duopoly consisting of GE and itself. GE has a 50% market share, while Rolls Royce has 30%; however, Rolls Royce has ~50% of the order book for new engine deliveries over the next decade.

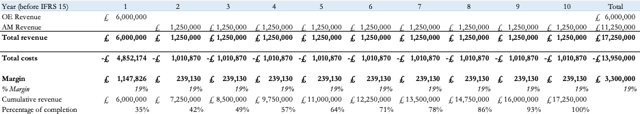

The investment cycle in this industry spans ~50 years, which makes this company extremely hard to value for public investors. After a ~10-15-year period of high investment, an engine manufacturer will sell these engines to airplane OEMs (Airbus (EADSF) and Boeing (BA), for instance) at a loss and enter into long-term contracts with the end-buyers of these airplanes (airlines like United (UAL)) for “maintenance, repair and overhaul,” or MRO services. These contracts last ~25 years in the wide-body segment, and these services are usually mandated by regulatory authorities and represent a small portion of an airline’s total cost structure (~1-2% of annual revenue). Rolls Royce can service these aftermarket (AM) contracts at a ~40% margin. Here are the cash inflows of a typical engine delivery for the company (not including development costs for the engine):

(Source: Author’s Calculations)

Over a long period of time, the goal of an engine manufacturer is to grow its “installed base” of engines in-service and collect these annuity-like aftermarket revenues.

Great Company, So Why is it Cheap?

Over the past several years, a conflation of factors has resulted in Rolls Royce’s underperformance. The first of which is the forced adoption of IFRS 15, which completely changed the way the company accounted for these long-term contracts. Previously, Rolls Royce would account for engine sales using a system mirroring percentage-of-completion or program accounting. Here’s how the engine sale above would be accounted for under the old system:

(Source: Author’s Calculations)

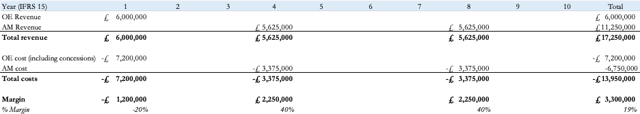

IFRS 15, however, did two things: (1) forced Rolls Royce to account for the total OEM cost at the time of sale, and (2) only recognize AM revenue when MRO services are actually performed. Here’s how the accounting would look under IFRS 15:

(Source: Author’s Calculations)

As you can see, if an engine manufacturer is in a period of high engine deliveries (like Rolls Royce), it will generally report a loss under IFRS 15. Immediately after adopting this accounting, Rolls Royce began reporting a loss, even though the underlying profitability of the contracts and cash inflows hasn’t changed. Moreover, companies like GE still use percentage of completion, which makes Rolls Royce hard to screen:

We have long-term service agreements with our customers predominately within our Power and Aviation segments that require us to maintain the customers’ assets over the contract terms, which generally range from 5 to 25 years… We recognize revenue as we perform under the arrangements using the percentage of completion method.

Source: GE 2019 Annual report

A combination of this complex financial model and limited disclosure in the company’s financial statements put it in the “too hard” pile for most investors. Moreover, the short-term mindset of sell-side and the fact that it is almost impossible to find Rolls Royce’s annual reports before 2003 have resulted in few actually evaluating this company on the basis of a full investment cycle. Given that IFRS 15 essentially tracks the company’s investment cycle, it is extremely paramount to understand this.

Valuation

How is Rolls Royce a cigar butt? The central question I considered is the following: abstracting from the effects of engine deliveries, how much would the company collect in current annuities if it stopped investing in its business? That is, if it stopped developing new engines and simply completed its contracted MRO services until completion of these contracts.

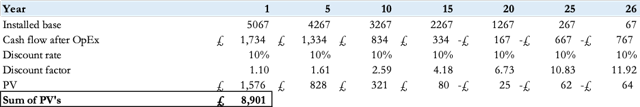

Rolls Royce currently has an installed base of 5,067 wide-body engines. This base generates on average ~£2.5 billion (5,029 engines*1.25 million AM revenue per engine*40% margin) in annual cash flow. On top of this, the company spends ~£1.6 billion in what it calls “fixed costs”: R&D, general operating costs and capex. In a runoff scenario, these costs won’t be as high (specifically R&D, which makes up ~£1 billion of these costs). Let’s say half of these expenses will continue to be spent in this run-off scenario. Netting this with our cash flows gives us ~£1.7 billion (£2.5 billion less 50%*£1.6 billion) in annual cash flows. Given an engine lifetime of 25 years, this installed base should decrease by ~4% per annum (1/25=.04). Using a 10% discount rate, our run-off valuation is ~£8.9 billion, or 468p/share:

(Source: Author’s Calculations)

Another way to look at this is to consider these cash flows as an annuity. The annual payment is ~£2.2 billion (aftermarket cash flows collected in 2019) less ~£800 million in maintenance OpEx, or ~£1.4 billion in cash flows every year. We will use the same discount rate of 10%. The average age of Rolls Royce engines is 8 years, and engines remain in service for 25 years, so the remaining “life” of these annuity payments is 17 years. The present value of this annuity is a very basic calculation in Excel:

PV(10%, 17 years, £1.4 billion) = ~£11.2 billion, or 589p/share

This all compares to a current share price of 327p. What makes this a cigar butt is the following: (1) this assumes a run-off scenario, when in reality, Rolls Royce is investing in new engines and this installed base is about to increase significantly; (2) the company has an order book for deliveries until 2030 for engines it has already developed – we assigned no value to these engines (which are on the order of £70 billion in gross value); (3) this assigns no value to Rolls Royce’s other businesses, which cumulatively generated ~£7.5 billion in revenue and ~£800 million in operating profit in 2019.

In essence, by investing in Rolls Royce, you are getting an annuity for ~60 cents on the dollar (average of two run-off valuations above relative to current price), plus a collection of other businesses giving you a 13% pre-tax yield (~£800 million/(19 million shares*327p/share)*100) on your initial investment. To reiterate, this opportunity exists for the following reasons: (1) Rolls Royce is a complex business that investors regard as a black box; (2) no one has bothered to look at the business over the course of a full investment cycle lasting 20-30 years; (3) the company is facing a myriad of transient issues that shroud its cash flow-producing potential over the next decade.

Catalysts

This is all well and good, but when will investors reward Rolls Royce with a more deserving valuation? The flip side of IFRS 15 is that it makes companies look even more highly cash-generative than they actual are in the later stages of the investment cycle. Rolls Royce has just entered in that period where it will reap the benefits of a growing installed base after a decade of investment:

The message is clear: after a decade of significant investment we are committed to delivering improved returns while continuing to invest in the innovation needed to realise our long-term aspiration.

Source: 2018 Annual Report

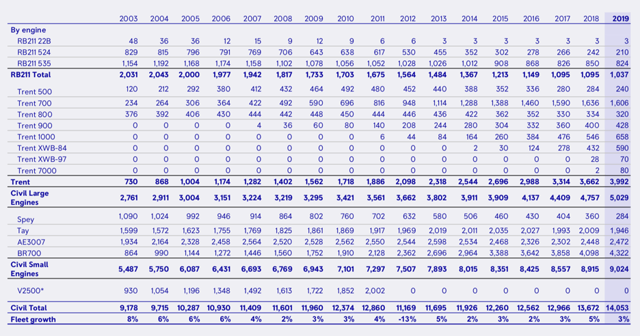

The significant investment here refers to the development of the newest generation of Trent engines, specifically the Trent 1000 and Trent XWB. These engines have only recently come into service:

(Source: Company Investor Presentation)

From FY2005 to FY2016, the number of large engines that entered in service was 986 (4,137 – 3,151). This slow growth was the result of a number of new engine programs – namely the Trent 1000, Trent XWB family and the Trent 7000 (a modification of the 700) – that were in development for most of this period and only recently went into service. From 2016 to 2019, we finally saw the ramp-up in engine deliveries as these newer engines entered into service. From FY2016 to FY2019, the number of large engines in service increased by 892 and are projected to increase to over 1,000 as Trent 7000 deliveries continue the ramp-up. This isn’t speculation: it is simply meeting the company’s order book that was built during the development period (the £70 billion I discussed previously).

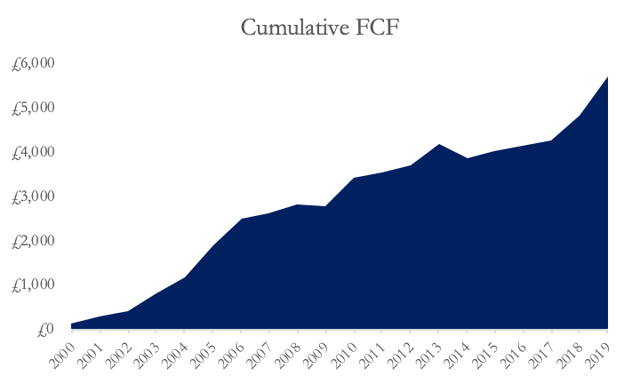

We saw a similar dynamic in 2000-2004 when the company significantly expanded its engine deliveries by ~1,000, albeit from a lower base. You can also see this in cash flow generation:

(Source: Author’s Calculations, Annual Reports)

To drive the point home, Rolls Royce generated its first £2 billion from 2000 to 2004 (cash generative period), its second £2 billion from 2005 to 2016 (development period) and has generated £2 billion in just the last three years. This is the beginning of a highly cash-generative phase in the investment cycle. Because of IFRS 15, accounting numbers will lag this cash generation (aftermarket revenues received in cash, but MRO services are performed later), but Civil Aerospace should go from a loss-making enterprise to a 12-13% margin business within the next several years.

Other Issues

There are a number of issues an investor should consider in addition to those discussed here. A complete discussion of them will make this article unbearably long. They include:

- The economics of the other business. However, I believe the margin of safety here is sufficient for these businesses to go to zero and this investment to still pay off.

- Coronavirus impact on aftermarket revenue timing and order book realization: aftermarket revenues are billed based on flight hours, and given that flying has been driven to a halt, this will change the duration of the annuities we talked about. There is also the issue of airlines going bankrupt. This is particularly a risk to aftermarket cash flows, which won’t be collected if aircraft permanently go out of service. However, Rolls Royce has a net cash position and more than enough flexibility in R&D/fixed cost spend to weather the storm. We assumed ~50% of fixed costs could be saved in such an environment, but management believes this number is far greater. When we look at a similar situation in 2001/2002, Rolls Royce’s engine deliveries were cut by ~40% and revenues dropped by ~20%, yet the company was still able to generate an operating profit on the order of £100 million. Nonetheless, many industry participants (for example, HEICO) have made it clear that the situation today is far worse than that in 2001/2002. While it is difficult to predict the severity/duration of this crisis and its impact on air travel, over the long term Rolls Royce has the capacity to meet a significant run-up in engine deliveries over the coming decades. Finally, the margin of safety in our valuation was substantial. We can assume a 50% decline in annual aftermarket margin – a fairly apocalyptic scenario – and still generate a margin of safety on this investment. I welcome a discussion in the comment section if anyone has informed views on the impact of coronavirus on this business.

- GE’s margin advantage: GE has ~20% margins vs. Rolls Royce’s mid-teens margins using percentage of completion. This is a result of (1) RR historically not controlling costs and (2) GE’s scale advantage. This is both a risk and an opportunity as RR increases scale, but it does give GE an inherent R&D advantage.

- Wide-body as an inherently disadvantaged vertical: Rolls Royce got into hot water for selling its stake in IAE, as many consider narrow-body to be an attractive business due to (1) more diversity of contracts/customers; (2) larger growth runway; (3) engines sold for narrow-body planes are typically sold at an upfront profit, which helps the economics (although MRO contracts are shorter). Given current order books, it will take many years before Rolls Royce can enter the vertical again.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, but may initiate a long position in RYCEF over the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Be the first to comment