KangeStudio

Are we heading for a recession?

This is the question on everyone’s mind as markets fell sharply during the second quarter on the heels of high inflation data points and the Federal Reserve Bank’s resolve to fight inflation even if it creates a recession. We think a better question is “what might a recession actually look like when (not if) it happens?” In the post-World War II US economy, we experience a recession once every six years and this includes the prolonged expansion post-Financial Crisis through COVID-recession.

Considering that our investment time horizon is five years, we always contemplate a recession somewhere within reasonable distance of our underwriting process on every investment we make. One cold, hard reality of investing that everyone must face is how there will be periods of expansion, periods that look like we might head for contraction, and actual contractions (what we call recessions). In other words, there is no investing without contending with near recessions and actual recessions, though we only know the difference between the two in hindsight.

One problem that many struggle with today is that outside of the COVID lockdown-induced recession of 2020, we have not experienced a recession since the Great Financial Crisis. Recency bias leads most to expect the carnage of any “next” recession to look like the Great Financial Crisis, rather than the more benign, typical recession of the post-World War II era.

To simplify, in an economy like the US, there are two kinds of recessions: first, the traditional variety; and, second, debt deleveragings. Let us be clear here: there are no good recessions, though recessions are necessary evils that cleanse excesses that build up over time in an economy. The distinction between the two kinds of recessions is important: the traditional variety is healthy and has a natural cadence, while debt deleveragings are destructive and can leave the entire economy “staring into the abyss.”

In our early years at RGAIA, we visited the recession question numerous times as people feared a “double dip,” the European crisis, the energy implosion, Fed hikes of 2018 and everything in between. We have consistently shared a framework that is especially important right now, for our expectation of what a recession will look like seems especially on point right now.

In our preview for 2015, we said the following: “Importantly, we think the next recession will come from an economy that accelerates too much and must be slowed down via a tightening of monetary policy, rather than one where a credit contraction puts us on the precipice of deflation. In other words, the next recession will be of the run-of-the-mill variety, which are never fun, but are far less troubling than once-in-a-lifetime financial crises.”

This explanation should sound especially familiar in light of recent events, with Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell evolving his language to now embrace the notion that a recession is “certainly a possibility.” Given the historical nature of “Fed Speak,” certainly a possibility might as well translate to “more likely than not,” though Powell continues to insist “we’re not trying to provoke…a recession.”

Will we avoid recession or end up in a recession? The truth is that there is functionally no difference for the market. Earnings estimates likely need to come down in either scenario, but the good news is that given any recession is bound to be of the traditional variety, there will not be forced deleveragings in areas that will permanently alter the trajectory of the economy. How can we say this so assuredly? Because outside of the Federal Government, total debt in the private sector is at very comfortable rates, especially at the household level.

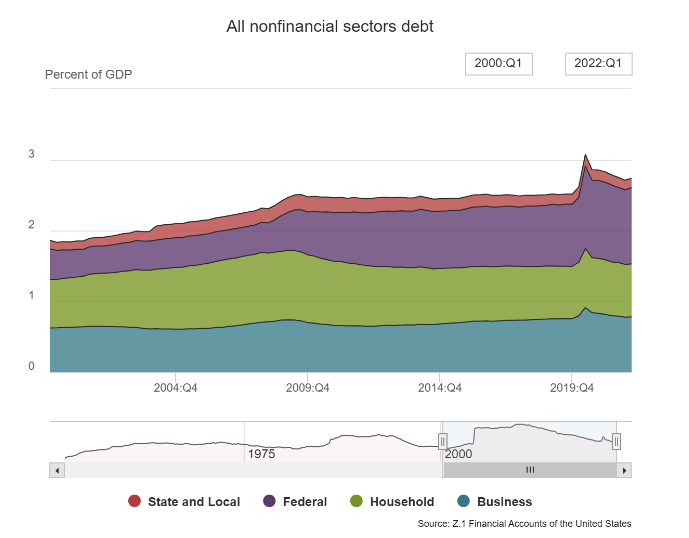

Further, the financial sector is as safe-and-sound as it has been in any of our lifetimes. If you recall the Great Financial Crisis, it was the financial sector’s excessive leverage that brought us to the brink of meltdown. We can see the leverage situation quite clearly in the chart below:

The picture would look even better on a net basis, showing assets less debt, though illustrating debt is more helpful for seeing why we ended up with major economic headwinds from debt deleveraging in 2009-2012. Households and the financial sector (not shown here) in particular were the areas that experienced most of the deleveraging. Add in the trajectory of interest rates and not only were debt levels brought down meaningfully, so too was the cost of the debt in absolute and relative terms, as the duration of debt was extended at the low prevailing rates.

This creates a constructive backdrop going forward. Some might question the extent to which the government has levered up, but that is exactly the role the government’s balance sheet is supposed to play when the private sector de-levers in order to ensure the heart of the economy continues apace. Consequently, going forward we need households and businesses to drive growth, rather than stimulus. In other words, we need a healthier economy.

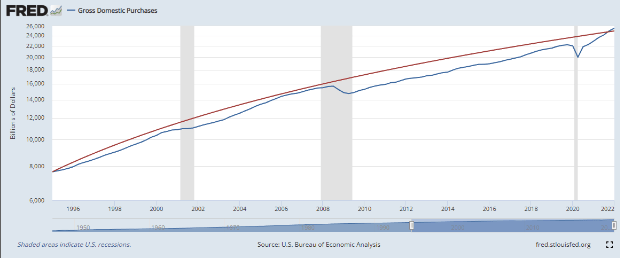

In the same 2015 preview where we spoke about what the next recession would look like, we also addressed the question of whether we were experiencing “secular stagnation.” There might be a helpful answer to the capacity of the private sector to support the next expansion. Below we are looking at Gross Domestic Purchases (GDP less exports).

The notch down in the blue line below the red in the shaded gray area between 2008 and 2010 is what has been called “secular stagnation”–the notion that the capacity of the economy to grow had been reduced by the Great Recession. With COVID stimulus, the blue line caught back up to the red line, and that raises the question whether we might actually no longer be facing “secular stagnation” and further begging as to whether more stimulus earlier in the GFC could have prevented our slower growth of the last decade.

Although it is impossible to prove counterfactuals, it’s worth thinking about whether growth from here can actually be better than the last decade.

One simple reality of markets is that when things get challenging in the economy, timeframes of the average investor shorten for various reasons. We always operate with a long-term mindset and that approach is even more advantageous today. In prior paragraphs, we mentioned how recessions are an inevitability and something we expect within our time frame in approaching any investment. No company is entirely immune to recessions, but our companies are not the kind whose business size and opportunity will change over the course of a cycle solely by virtue of what happens in a recession.

Moreover, our companies operate with a substantial amount of net cash. As such, the balance sheets in our portfolio are a source of opportunity rather than risk. Leverage can destroy a sound business in a recession if the structure is too risky, meanwhile net cash can be used for opportunistic repurchases or strategic M&A that accelerate a company’s growth once the downturn inevitably ends. To give an example for what we mean: in the 2008 downturn, banks had to dilute their equity holders considerably in order to rebuild their balance sheets and operate going forward with considerably less leverage.

These changes permanently altered the earnings power of banks. Today, a recession means a short-term reset in expectations both on revenue and earnings, but it does not mean that at some point over the next five years when a normal environment returns, that our companies’ earnings power will be any less. This is important for riding out the storm with conviction.

Macro to micro

With this as a preface, we need to talk about inflation, recession risk and what it means for our stocks. As we have been emphasizing through this period of higher inflation, the average company in our portfolio predominantly deploys intangible assets and generates considerable free cash flow, thus rising input costs by and large infect our portfolio far less than they do the S&P at large. Plus, our average company boasts considerable net cash and little to no debt.

This is important as interest rates rise, for our portfolio companies will not be exposed to rising rates in their earnings and cost structure. Rising rates do flow through in terms of the discount rate of cash flows, but importantly, in our analysis through the two extended periods of ZIRP, we have never assumed permanence of low rates and have valued companies based on “normalization” of rates at some point

That said, the heightened macro volatility does still lead to problems. The fact that these problems are occurring immediately on the heels of considerable successes left many caught flat-footed investing behind growth, on the expectation of further growth, only to have revenue slow. Investments cannot be reversed immediately and therefore some of these companies have been left with too bloated a cost structure for the reality of today’s environment. This is not ideal, but also not catastrophic.

Two of our portfolio companies, both UK listed small caps, unfortunately have considerable exposure to rising costs–Naked Wines (OTCQX:NWINF) and Fever-Tree Drinks (OTCPK:FQVTF).

Naked Wines fell victim to a challenging environment whereby during COVID, inventory levels were too light to fulfill demand. The company then ordered more inventory that sat in port for too long, so to preempt further problems, the company continued a steady state of inventory acquisition. Meanwhile, new customer acquisition slowed. This left the company having invested far too much money in inventory and facing the tough choice of paring back some growth spend or taking an asset-backed loan in a tightening credit environment that featured some tough covenants.

Unfortunately, we think the company made a mistake in judgment – continuing to plow ahead with their growth plans irrespective of the changing and challenging post-Covid environment. This left shares vulnerable as risk-appetites receded. The silver lining here is that although shares have taken a beating, the core business continues to feature stronger retention of existing customers than we ever expected, especially moving beyond the COVID period.

Further, we think the company is appropriately considering the tradeoffs in light of today’s new realities and will be positioned to consolidate their strengths and recover value in a reasonable amount of time.

As it stands today, Naked Wines is valued at less than the inventory on their balance sheet. They are also valued at a steep discount to the runoff value of their existing customer base. These two ways to approach liquidation offer a substantial margin of safety, because either sharp investors or a strategic buyer will find this value far too compelling to pass up for a strategically significant asset.

Fever-Tree pre announced earnings shortly after the end of the quarter and the market reaction was abysmal. There had been some concerns whether the premium price of the product would lead consumers to trade down amidst tightening budgets. This was not the case, as revenues continued to exhibit strength. The problem was that inflationary pressures on glass and a tight labor environment in the US prevented the company from fully launching their US manufacturing plans and realizing anticipated cost savings.

We think management is making the tough, but prudent choice to continue to serve demand in the US from UK production, despite the near-term hit to margin. The fact that this happened after several quarters of declining gross margins made some investors lose faith in management; however, we deeply believe that these margin pressures will sort themselves between supply-chain normalization and actions taken by management which need to flow through.

Far more of the value over our expected holding period will result from how big the premium mixer business can be than from what point the company achieves the optimal margin structure. Immediately following the earnings report, Fever-Tree traded at its lowest forward multiples ever, on what would be less than half their historical average margin. Trough multiples on trough margins is a potent recipe for strong future returns and we are not surprised shares have swiftly recovered most of their swoon.

Things will likely remain volatile from here, but even if the company never grows again and margins do not recover (and let us be clear: we expect both growth and a margin recovery), the stock would be as cheap as anything in the beverage or spirits industry.

Value is growth, growth is value

Although our companies tend to be more insulated from inflation than most, they tend to reside on the “growthier” end of the spectrum. In essence, our portfolio companies in aggregate make less free cash flow (though still healthy amounts of it) today than the S&P, but they also grow at a faster clip. With concerns about growth, the market has favored so-called value stocks, while punishing those which exhibit growth.

Consequently, many former growth darlings now qualify as “value” stocks to the point where the Russell 1000 Value Index even includes our growth holdings. A great example of this is one of our recent purchases: Meta Platforms (META, the company formerly known as Facebook). As it stands today, META is the fifth largest holding of all in the Russell 1000 Value Index.

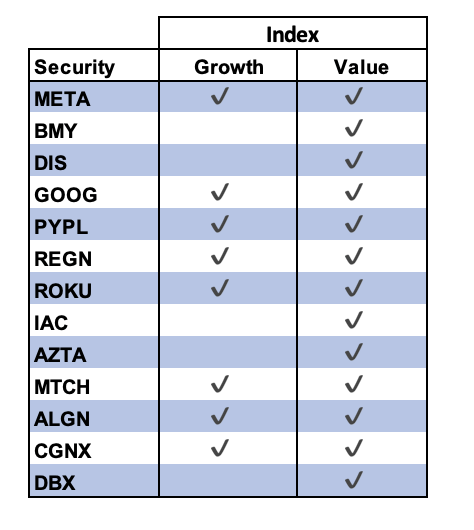

We have always self-described as GARP investors, meaning we want to find growth at a reasonable price. Further, we require growth, reasonableness of valuation and quality, while also looking for strategic significance, optionality and some degree of change. We have 22 core holdings today, five of which have their primary listings on international markets. Of the 17 remaining holdings with US primary listings, 13 of them are constituents of the Russell 1000 Value Index, which represents the universe of large and mid-cap “value” stocks in the US.

Of those 13 value constituents, 8 also appear in the growth index. In fact, today, we have more holdings in the “value” factor than in the “growth” factor, though despite this reality, our portfolio still trades predominantly with growthier stocks. Although this hurt us lately, we are confident the day will come where stocks with strong growth and demonstrable value return to the market’s favor.

Below are the 13 holdings in the value index and their status in the growth index as well:

Why are we sharing this? First, because we want you to understand that our portfolios consist of companies with demonstrable (in contrast to creative) value, that clearly checks the established criterion of a systematic value strategy. Second, we find it incredibly interesting and notable that growth has become value in today’s market. Over the course of our careers, no such period has existed where one can acquire so much growth at value prices.

Therein lies both the problem and the opportunity. The problem is that in the very near term, market timeframes are shrinking and while growth estimates of these companies get slashed, few buyers want to step in; but, the opportunity is for those who can look through to a day when the economy either avoids or gets past a recession, the dual forces of growth and value compounding on one another will lead to especially favorable outcomes.

The opportunity of today

Let us now turn to the reality of bear markets. It is easy to question every sale not made and every purchase. Bear markets wear on investors and provoke self-reflection, introspection and unfortunately, some degree of doubt.

The truth of the matter is that these are actually the kinds of environments where the real returns are made. Timeframes of the average market participant shrink from years to days. People isolate on the most recent datapoint and extrapolate that ad finitum. To an extent, this kind of over-extrapolation has been in place from the moment the COVID crash started, but today we are at a juncture where extending one’s timeframe is the most important way to inevitably reap solid long-term returns.

We have always operated with a long-term mindset. On what might be the eve of recession, with markets already down substantially, it is that much more important to think about what the world looks like on the other side (ie post-recession) than in it. The exception is with those companies whose balance sheets provoke concerns about their ability to survive an adverse environment. There is this common saying right now: “the market has repriced the multiple, now we have to price the right “E” for earnings.”

It’s been asserted by many and it sounds appealing, but we strongly disagree with the premise. We would phrase it as such: “the market has repriced the multiple BECAUSE it does not trust the E.”

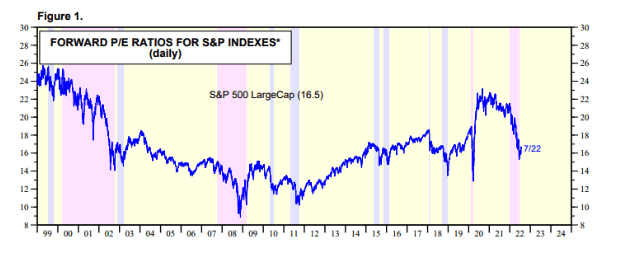

Here is how it looks as of today, with the repricing even more acute in smaller capitalization stocks:

source: Stock Market Briefing: Selected P/E Ratios

Those who proffer this argument about the next leg reflecting earnings risk suggest the multiple has repriced because the risk-free rate has moved higher since the start of the year. This is true and we would be remiss to not accept that some portion of multiple compression stems from the rise in the 10-year in particular, but the repricing in the market’s multiple has been more extreme than what would be justified by the 10-year alone and the market’s multiple is now lower than it was when the 10-year was at similar levels before COVID.

Multiples and earnings are inherently tied at the hip. One would pay a higher multiple for more growth. When growth estimates come down, so too does the multiple. We believe our argument is correct for two primary reasons: 1) the “repricing of risk” started in the growthier COVID beneficiaries long before the 10-year commenced its ascent. This area of the market started feeling pain when it became clear growth rates had peaked and there was little clarity on either the magnitude or length for how the growth curve would slow down.

To date, this pocket of the market has experienced the most dramatic multiple compression of them all; and, 2) some of the most extreme down moves have happened on earnings disappointments themselves over the past two quarters. This is true of specific stocks and the market. At the very least, earnings have been a substantial part of the repricing here.

Recent market actions

Early in the second quarter, we sold our Twitter (TWTR) shares on the official announcement that Elon Musk would acquire the company at $54.20 per share. Although we typically would wait for what was then a large 7% merger/arb spread to close, we figured in this market environment it would be beneficial to move aside in the event future drama might ensue while building cash in order to opportunistically deploy into better opportunities. During the quarter, we saw the chance to do so and bought shares in four companies.

In the process, we are also broadening our portfolios and diversifying into more ideas. There is a tradeoff between concentration and diversification, but in times like these when the market is throwing many stocks out of the window (or “babies out with bathwater” as the saying goes), broadening the aperture of opportunity is a worthwhile endeavor. The more positions we have that fit our criteria, the more chances we have for something to go right for us and the less any one risk factor can further hurt the portfolio. We will briefly cover each in the following paragraphs.

Meta Platforms, Inc (META) f/k/a Facebook— we followed Facebook for years and were often asked “why own Twitter when you can buy Facebook?” Sure enough, Twitter’s return was far better over our holding period and we now deployed a decent portion of our Twitter proceeds into META. META today strikes us as one of the cheapest stocks in the entire market and one of the more interesting setups we have seen. META was hit with a triple-whammy of tough COVID comps, changes in Apple’s privacy policies and emerging competition from TikTok.

Despite all this, the company continues to grow, albeit at slower rates. At its lows this year, META was trading for a low teens forward P/E (15x 2022 numbers today) and this is despite investments in the Reality Labs division at around a $10b annualized rate. If we exclude the Reality Labs investments, the core META properties of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp would earn somewhere around 23% more in bottom line EPS. This would chop about 2.5 turns off the company’s P/E.

Speaking realistically, there is no sign Mark Zuckerberg would entirely stop these investments; however, we do think Zuckerberg is realistic about his stock price and very well might defer a large portion of the investment until core earnings reaccelerate. Further, we think it is appropriate to value the company on a sum of the parts basis and rather than fully expense the Reality Labs investments against the core properties, we should think about what the actual value of that investment might yield. Either way, even fully expensing Reality Labs, this company is far too cheap to ignore.

Align Technology (ALGN)– we have followed Align with admiration for years. The company has consistently executed its combination of profitable growth, while disrupting the orthodontics industry and enhancing its offering beyond the pure product. Specifically, Align’s Invisalign is by far the best clear aligner and the company has used its offering to build what is essentially the “operating system” foran orthodontics practice. COVID Stimulus led to a surge in demand from which there is now a hangover.

Consequently Align is at its lowest valuation multiple in a decade (sub 15x EV/EBITDA); lower than when fears of a patent expiration led some to believe emergent competition could derail Align’s momentum (it did not). Align is more “discretionary” than the typical healthcare company, because their core clientele are adult patients with orthodontic problems. This means there is some portion of cyclicality; however, the really long-term opportunity is capturing the core teenager orthodontic industry, which remains the vast majority (over 80%) treated with metal braces.

It is inherently more challenging to drive adoption in this demographic considering invisible aligners are more expensive and require patient compliance, though we think the generation growing up seeing themselves on Instagram and TikTok will inevitably steer towards clear, where Align is dominant. As they say, the future here is bright.

Cytek Biosciences, Inc (CTKB)– Cytek is one of those companies we think might end up a true gift from this environment. The company went public in 2021 and raised considerable capital due to the enthusiasm of the opportunity for Cytek to fundamentally change flow cytometry–a critical piece of biological research and diagnostics to analyze cells or particles. Flow cytometers are everywhere, though we do not often hear about them.

Fast forward to today and Cytek’s shares have collapsed from the IPO price, despite the company being free cash flow positive and holding 30% of its market cap in net cash ($362 million). The company’s proprietary technology replaced expensive vacuum tubes with much cheaper avalanche photodiodes, which allows for both higher precision, faster throughput and most importantly lower cost of ownership and operation. What customers don’t want better quality at a lower price?

Competition is not even close. Cytek sells flow cytometers, but importantly they are now building a reagent business to complement their instrument. This means they will have a razor blade and business model, selling the instrument with a nice profit margin and the reagents for throughput at an even better margin. Despite considerable growth investments, the company is profitable (on an adjusted EBITDA and cash flow basis) today and will be even more so in the future.

MacCyte, Inc. (MXCT)– Cell and gene therapies are the frontier of innovation in biotech. MaxCyte is uniquely well positioned to benefit, irrespective of who the precise winners are, as a pick and shovel provider to the industry. MaxCyte develops and sells electroporation instruments, that possess “unparalleled consistency and minimal cell disturbance.” Like Cytek, Maxcyte boasts a razor and blade business model, with high gross margins on both the instrument and consumable piece.

The instrument is mission critical to edit the DNA of a cell outside of the body and it cannot be used without MaxCyte’s proprietary consumables. In research, customers use a single instrument, but as a study moves to the formal FDA clinical process more instruments are deployed and on an approval down the line, far more. Beyond the razor and blade revenue pools, MaxCyte’s tools are so valuable that their customers sign on for “Strategic Platform License” (or “SPLs”) arrangements.

SPLs offer MaxCyte licensing revenues as milestones are achieved and a percent of revenues once a treatment is approved for use. The company is partnered with 17 leading cell and gene therapy companies for these SPLs. Not only would a single approval from one of their 95+ partner programs justify the current valuation, but significantly more than one approval is plausible.

On top of this, we purchased MaxCyte at a price where over half of their market cap is pure cash and at their present rate of burn, the company has over a decade of cash needs covered. As such, the market is giving very little credit to a high quality business model with unique optionality.

The high price of an important lesson

While this environment has not been conducive to investing in equities, we are quite frustrated with our own relative performance. Despite a challenging macro environment, we view our predisposition towards inaction in our best ideas as a failure of our own making. This tendency has served us well for almost the entirety of the last decade and it has cost us mightily of late.

We must ask ourselves: should we revisit our low turnover objective or is there something else underlying today’s predicament that can help us navigate similar environments in the future? We ask these questions because it is how we are wired and because we know we can do better.

One of the traits at the core of what we do at RGA is to constantly learn, grow and advance. Our preference is to learn from history books; however, inevitably some mistakes we must make on our own in order to internalize and synthesize the right lesson. An unfortunate reality with markets is that there are no second chances to make up for past mistakes, though the beauty is that in pursuing investing as a lifelong endeavor there are an infinite number of opportunities to deploy past learnings down the line. Not only can we do better, we absolutely will do better.

Looking backwards, we can identify two distinct problems:

- In the rebound from the COVID crash, our portfolio concentrated itself into a certain kind of position. This was not an explicit endeavor on our part, in fact, we felt the portfolio was fairly barbelled between COVID losers and COVID winners. As the winners soared in tandem and the losers stagnated, the majority of our book consisted of companies sharing two critical traits: high growth and a digital-first offering. In the past, we have experienced epochs of time where our portfolio holds one or two large winners. From the beginning, we have had a self-calibrating procedure, whereby our position-size ceiling would require a sale, even if we still believed in the value and prospects of the business.

- In 2020 through early 2021, with so much of our portfolio moving in tandem, only one position reached our size restraints and that one, we did indeed trim. This led to a large realized capital gain and caused us to believe we had more time to gradually scale out of some COVID winners in order to once again own a more balanced portfolio.

Part one reflects how we lacked a self-calibrating process when a large part of our portfolio functionally becomes one trade. This ties in with part two, which is the behavioral reality of the situation. The purpose of automatic constraints is to take some degree of decision-making away from decisions that might get clouded by judgment call. One frustrating reality of this present situation is how we recognized the degree of over-concentration in a certain kind of stock.

We started the process of gradually paring back winners and reallocating to newer areas; however, we felt there was time to spread the inevitable tax hit over years rather than realize everything immediately. There is a degree to which we are unsure the events that have transpired over the last two years will ever reappear, but we are in the process of considering what the appropriate constraints should be. What will not change is that we very much believe over the long run, letting winners ride is critical to exceptional results and letting companies intrinsically compound is critical for optimizing after-tax results.

We do know something important that will be different in our portfolio management process from here: we will pay more attention to the correlations between the positions in our portfolio and when an uncomfortable amount of our portfolio is acting functionally as one trade and keeps taking on an outsized share of our portfolio, we will be deliberate in paring back exposure. Over time, we will more clearly articulate what this looks like, but for now it is a rule that includes something that is objective, applied with a degree of subjectivity.

Thank you for your trust and confidence, and for selecting us to be your advisor of choice. Please call us directly to discuss this commentary in more detail – we are always happy to address any specific questions you may have. You can reach Jason or Elliot directly at 516-665-1945.

Warm personal regards,

Jason Gilbert, Managing Partner, President | Elliot Turner, CFA, Managing Partner, Chief Investment Officer

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment