imaginima/E+ via Getty Images

Investment thesis: In a recent article entitled “‘Watch The Fed’ Era Ends For Investors, As Commodities Scarcity Era Begins,” I pointed to the diminishing value that central bank watching has for investors. Watching for the future availability of crucial resources such as oil can have far better forecasting value, given the new era of scarcity, we find ourselves in. It is a simple concept, not unlike estimating how far one can hope to go on a tank of gas.

Since I wrote that article, we are now getting an increasingly clear picture of where we stand in terms of a coming severe global oil supply/demand imbalance, which is now just a few months away. While most analysts continue to focus on the world’s major central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, which is by far the most important one of them all, the widening global oil supply/demand gap suggests that we are very likely to see an oil price induced recession as early as the first months of 2023. Investors should be able to ride the commodities bull market for the rest of the year, after which they should consider bracing for a downturn, and buying opportunities coming out of it.

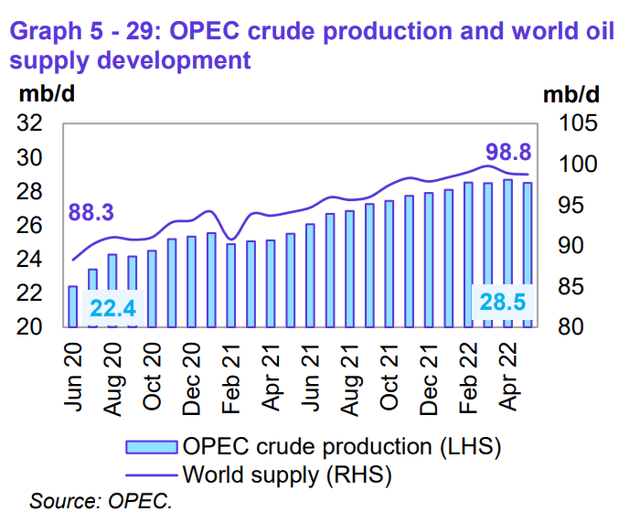

OPEC estimates suggest we have a 4 mb/d supply gap to fill between now and the end of summer.

As of May, global liquid fuels production stood at 98.8 mb/d, while global demand is set to reach 102.8 mb/d on average throughout the fourth quarter of this year.

Global liquid fuels monthly production (OPEC)

In short, whatever happens between now and the coming fall in terms of global liquids supplies, it has to add up to an extra 4 mb/d in output in order to bring the market into balance.

The IEA forecasted in its latest monthly report that we should be more or less alright for the rest of the year, with things getting more uncomfortable next year. Based on the latest information available to us, it may be the case that the IEA is missing the real picture, with some flawed assumptions built into its forecasting models, and an oil market crunch may be just a few months away, with a recession sure to follow. In the absence of adequate supplies, demand destruction will be the only mechanism left to bring the market back into balance.

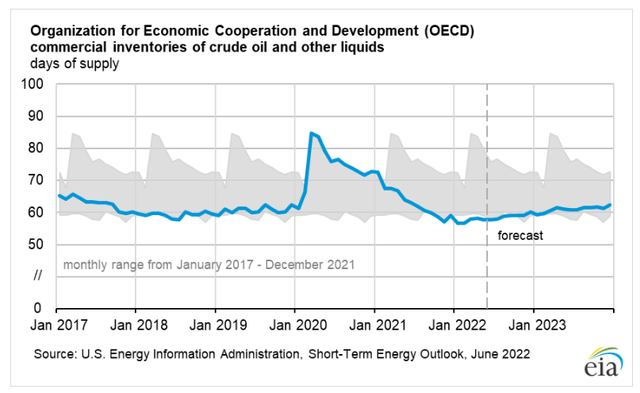

The emergency inventory release is set to end within a few months, just as we will see a jump in monthly global demand volumes.

In order to cushion the blow to the global oil markets stemming from a decline in Russian oil exports, due to the ongoing economic war over its invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. together with other OECD members decided on a substantial release from government emergency reserves. The U.S. committed to 1 mb/d being pumped out of emergency reserves back at the end of March, for a duration of 6 months. Earlier that month, OECD members collectively agreed to a 60 million barrel release from emergency stockpiles, which the markets largely greeted with a shrug.

The release of emergency reserves helped to sustain OECD commercial inventories.

OECD commercial oil inventories (EIA)

While the EIA seems to be doing its best to keep to a rosy forecast for inventories going forward, the actual data suggests that despite the emergency inventory release, we are just barely hanging on in terms of commercial inventories not sinking to critically low levels. At the end of September, we should lose the injection of about 1 mb/d of emergency reserves into commercial reserves. This is set to happen, just as we will see a jump in global liquids demand from 98.2 mb/d in the second quarter, to 102.8 mb/d in the fourth quarter.

Macron’s worrying conversation with Biden

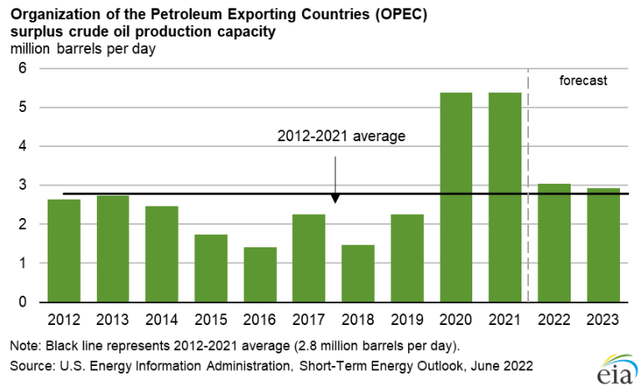

It is currently widely assumed that OPEC has about 3-4 mb/d in spare capacity that it can tap in order to help balance the oil market in the coming months. The planned Biden trip to the Middle East region is thought to be an effort to get the likes of Saudi Arabia and the UAE to ramp up production in the coming months. A recent revelation that a Macron-Biden private conversation casts doubt on spare capacity availability may suggest that President Biden may be wasting his time.

The OPEC + deal is already seeing a severe shortfall in terms of actual supply gains, versus the monthly production quotas that the agreement allows for. What this means is that expectations have already been dashed in regards to OPEC + spare capacity. Right now the Macron-Biden conversation amounts to only a rumor. It could be that the UAE leadership, which is cited as the source of Macron’s information, just wants Western leaders to stop pestering on the issue, so maybe he just said; “I don’t have any, just leave me alone”.

Shale will not come to the rescue, regardless of public policy measures

As the price of gasoline and diesel starts to bite consumers at the pump, inevitably political arguments will seek to dominate the shaping of the narrative in a manner that best serves their interests. For this reason, on the right side of the ideological divide, the argument is made that all would be fine if it were not for the left, which currently controls the levers of power. The argument is not without merit. The U.S. administration is currently hostile to the fossil fuels industry, and it did make some decisions that are by no means beneficial in terms of the current situation. Opposition to oil & gas infrastructure projects, or to drilling has had a direct negative effect on current oil & gas availability. It can be argued that the hostile tone alone is enough to curtail oil companies’ willingness to risk investing in more production, transport & refining of oil.

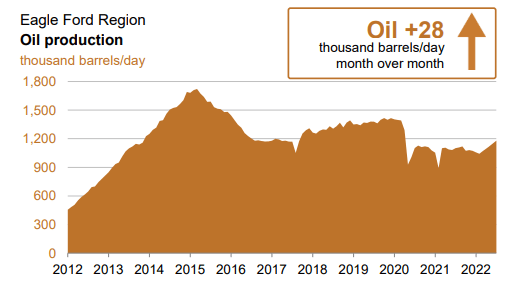

Having said that, it is far from reality to claim that if only the Biden administration and congress would not be so hostile to the industry, things would be mostly alright. Of the three major oil-producing shale fields, namely Eagle Ford, Bakken, and the Permian Basin, two of them have seen production peak before the Biden administration took office. In fact, Eagle Ford peaked towards the end of Biden’s stint as Vice President, and never showed any signs of recovering back to those peak levels during the four years that Trump was in office.

Eagle Ford oil production (EIA)

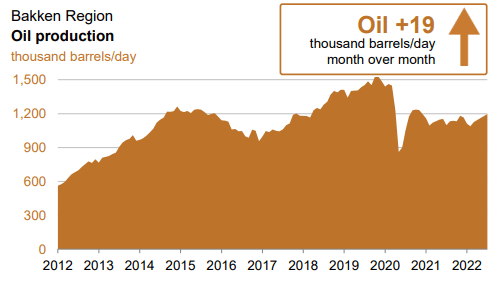

The Bakken field peaked a few months before the COVID outbreak, and it has been producing at a stagnant level for the past year, well below those peak production levels.

Bakken oil production (EIA)

The main reason why these fields are seeing a lack of interest in more drilling is that the premium drilling locations have mostly been exhausted. Second-rate drilling opportunities would require confidence in high oil prices being sustained, not for months but for years to come. It is a risk that many shale companies are not willing to take, after nearly going bankrupt trying to produce some of that second-tier acreage last decade.

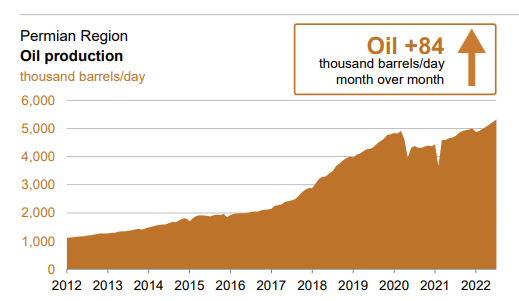

It seems that the Permian is not affected much by the hostile administration’s policies towards the oil industry. It is still seeing robust production growth, which suggests that companies are still sitting on significant prime acreage reserves.

Permian oil production (EIA)

Because it contains far more ample prime acreage reserves for shale companies to drill, it grew into a field that now produces about twice as much as the Eagle Ford and Bakken combined. Production will continue to grow, regardless of policies. When it will see a permanent peak, like Bakken and Eagle Ford did, the main factor that will cause it to peak will be diminishing prime acreage drilling opportunities. In the meantime, it will be the main source of US oil production growth in the coming months and years. With one field providing the bulk of US production gains, it will do very little to help close that 4 mb/d global supply/demand imbalance, which currently does not account for any further declines in Russian oil exports we might see along the way.

The Russia factor

The EU import ban on Russian oil, which includes measures meant to prevent Russia from shifting exports to Asia is supposed to come into play by the end of the year. It increasingly looks like it is unlikely to have the desired effect. It would only work if the EU would be able to get other producers to either increase production or to get them to shift their exports mostly from Asia, to Europe. The first scenario looks increasingly like a non-starter, as I pointed out in regards to OPEC and U.S. shale prospects. There does not seem to be enough new production coming on line to cover the expected growth in demand in the next few months, so certainly there is no oil available to replace any potential loss of Russian oil exports.

The second scenario is somewhat more plausible, but it also faces some significant headwinds. I personally cannot see OPEC members being overly receptive to the idea of losing market share in Asia to Russian oil exports while gaining market share in Europe, where demand is stagnated, and plans are in place to do away with all internal combustion vehicles by 2035. There is a very real risk that Russia, Iran, and Venezuela will have their sanctioned and discounted oil prices matched by discounts offered by the likes of Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, and Iraq in Asia, while the EU will see a massive price gap open up between the average sale price of oil in Asia and what it will have to pay to have oil delivered to its own shores. The prospect of such a scenario coming to pass may seem to defy any reasonable expectation at the moment. It may not seem as far-fetched a few months from now. We do live in interesting times.

The latest idea on Russian oil sanctions, coming out of the G7 meeting seems even more outlandish. The idea is to introduce a coordinated price cap on Russian oil exports. The very obvious flaw with the plan is that Russia can easily counter with a “take it or leave it” position. It is a seller’s market at the moment, after all. If not enough buyers will pay the minimum price that Russia demands, it can just gradually limit supplies, lifting all global prices, and the desire to continue with such a price cap scheme will quickly diminish. Based on these two initiatives, it seems that our leadership is failing to fully grasp the idea that we are very deep in a sustained commodities seller’s market, which is especially the case with oil & gas.

OPEC assumed spare capacity (EIA)

My guess is that advisers to Western government leaders simply took a look at reports, such as the one the EIA has provided, and took it for granted that OPEC members can increase production by 3 mb/d if need be. They failed to do any verification in regards to how reliable they can expect such reports to be. It is not like it was the first time that these spare production assumptions turned out to be wrong. If we think back to the pre-2008 period, as oil prices were spiking Saudi Arabia and OPEC failed to produce anywhere near the capacity they claimed to have. What followed was a massive oil price spike, which arguably helped to burst the housing bubble.

Global recession by early 2023 if we lose significant volumes of Russian crude exports. Full normalization of relations with Russia, Iran & Venezuela will buy us a reprieve to the middle of the decade.

The implications of the global oil supply situation are as simple as can be. Within the next few months, we have to provide a global increase in oil production of close to 4 mb/d in order to bring the market into balance and avoid a severe oil price spike. The only possible alternative is demand destruction. It can be triggered by allowing price rises to make it happen, or it can be triggered artificially through monetary means, but either way, demand needs to be brought into line with supplies.

The assumption that the world had enough capacity to meet the demand growth levels we are forecasting starting this fall and beyond was questionable even before the war in Ukraine and the resulting economic confrontation that threatens the world’s access to crucial Russian energy supplies. In order to avoid a severe global economic downturn necessitated by the need to close the oil supply/demand gap as soon as this fall, we need to avoid losing any more oil supplies, while all the sources of potential new supply will need to come through.

Beyond this year, we will need to see a return of Iranian as well as Venezuelan oil to the markets in order to continue meeting higher demand. The IEA is forecasting an increase of 2.2 mb/d, so we are not in a situation where we just need to meet the surge in fourth-quarter global oil demand, after which we can breathe a sigh of relief. If we do everything right in terms of facilitating the market presence of every barrel of oil the world can provide, we could potentially avoid a recession all the way to the middle of the decade.

Investment implications

I am sure that most investors have noticed the market reaction to bad economic news in the past few months. It is generally greeted in a positive manner, with some investor optimism. The main reason for it is that it is thought to be an argument against further monetary tightening. That in turn, is thought to be positive for the markets. Perhaps in a best-case scenario, weak economic activity will by itself lead to a decline in inflation, removing the need for central banks to act. A return to low-interest rates and QE meant to support the economy is thought to be just the thing that is needed to further inflate the stock market.

The aspect that investors seem to be missing in their Fed calculations is the fact that in the absence of a central bank-induced recession, we will likely have one just a little bit further down the road caused by oil prices spiraling out of control. The danger of such a scenario is that continued central bank monetary support for the economy will end up inflating prices in the real economy, rather than inflating stock prices, as we became accustomed to seeing since 2009. In other words, it only worked as long as there were no major issues in regard to global supply/demand. within the current scenario, loose monetary policy could exacerbate the commodities price spike, causing a deeper recession.

My strategy for this situation remains to be heavier on commodities-related investments. I have been adding small positions in non-commodities-related stocks lately, given that many are significantly off their recent or all-time highs, due to the overall market decline. I bought stock in AMD (AMD), Greenbrier (GBX), BASF (OTCQX:BASFY), Dow (DOW), Fusion Fuel (HTOO), Nokia (NOK), and Rivian (RIVN). The list is long, however, I should specify that the weight of any of these stocks within my portfolio is small, in the 1% to 3% range each. There are specific reasons I chose all these stocks and I recently covered some of them, as I entered the stock positions I mentioned above.

I am also sitting on about 30% cash, which is in my view a good reserve to be sitting on in order to take advantage of coming opportunities to buy. This ratio may increase slightly if the commodities-related stocks I am holding will continue to see a rise in stock values. For instance, the average price I paid for Suncor (SU) stock I am holding is currently about $22/share, while it is trading at around $35. I am looking to slightly reduce my position if the stock price approaches or surpasses $40, which would add to my cash position. Suncor is by far my largest stock position, making up about a sixth of my total portfolio. There is some risk to having such a large cash position, namely the fact that I could always be wrong, and there will be no recession, but a robust return to a bull market in stocks, at which point cash will be sitting on the sidelines, while the market will keep going up.

Given the increasingly uncertain investment environment, we are in, I am making it a point to maintain a robust position in precious metals. I have some physical gold & silver. I have Barrick Gold (GOLD) stock, I have some gold (GLD) funds, which I find to be a convenient temporary way to adjust one’s gold position. I also have some Wheaton (WPM) stock in my portfolio.

There are a few other stocks or ETFs I left out of the conversation in my portfolio, but the ones I mentioned do add up to a much longer list than I used to have on average, throughout my nearly two decades of investing. In fact, the total number of stocks in my portfolio is now about three times larger than it has been on average in past years. I decided to make a fundamental change to my overall investing strategy this year, namely seek diversity of investments, through different sectors, as well as have some geographical diversity. I see the overall investment environment for this decade as a minefield, with an endless number of factors causing a great deal of rising risk to any investment position that one can think of.

While in the past seventeen years of trading I only took a loss on three investments, I expect quite a few of my expanded list of stocks in my portfolio to end up being losers. In the past, I was willing to wait it out for years while fundamentals kicked in as I expected things to go, even if I was often underwater on certain stocks, at times for months or even years. It was a strategy that required a lot of patience, and faith in one’s own analysis, even in the face of being in disagreement with broader market trends, but it was also a strategy that mostly paid off, with steady, if not always spectacular returns.

With the new strategy in place, I expect to see far more spectacular returns, on investments held for a shorter duration, which will be counterbalanced by more frequent, deeper losses. I expect that the coming recession if it will pan out the way I expect it to will provide for a good opportunity to get in on some decent investments. In case it does not pan out, I will continue taking up minor positions in stocks I will identify going forward as a buying opportunity. Markets are already down significantly YTD, so there are some buying opportunities out there. Keeping some cash available for current and coming opportunities will be one of my main goals, even as I continue identifying buying opportunities.

The prospect of an oil price-induced recession sounds bad, and it is bad, especially given the low probability that we will find ourselves in a much better position to meet the world’s liquid fuel needs on the other side of the downturn. We will find that a recovery will quickly, at most within a few short years will hit another oil price-induced brick wall. Of course, much depends on what we will do going forward. It goes without saying that a growing understanding of the problem coupled with some competent planning would greatly improve the odds of avoiding an impending recession. Collaboration with other states meant to restore the global supply chains could still change the current bleak trajectory we are on. Lifting all impediments to getting more oil onto the market could buy us a few years. Those few years could be used to ramp up EV production and sales, which of course requires more collaboration among competing states in order to make all the resources available that are needed to make it happen. Of course, anyone who ever picked up a first-year economics textbook and got to the section on game theory applications knows that this is unlikely to happen.

A global recession is therefore the most likely scenario within the next 12 to 18 months, regardless of what central banks will try to say about it. “Watch the Fed” is done, it is just that the market is yet to read the memo.

Be the first to comment