Moving A Piano on a Spiral Staircase: Balance Is Everything

Introduction

We now have our $2.2 trillion government rescue packages in place for the ongoing health and economic crises. The Federal Reserve has also initiated unlimited “QE,” plus a host of loan guarantee and credit programs, and these could easily boost the Fed’s balance sheet by another $5 trillion within a year or two, starting from its current base of over $5 trillion (John Mauldin, 2020). Much of this largess will be used to at least partially monetize federal deficits that could potentially explode by over $6 trillion just through 2021. The rest will be used for corporate bailouts, much as we saw in the crisis of 2008-2009. The pressure all of this spending and monetary extravagance will exert on the real economy is hard to predict. In effect, we are experimenting with helicopter money (incrementally), as well as massive “QE,” “ZIRP,” and federal debt monetization on a massive scale.

There are no real precedents for this, and it is anyone’s guess what the price will turn out to be. It is possible that much of what’s being done will actually help, but that would require real balance in our approach, and also careful adherence to lessons learned throughout economic history. But in the perceived urgency of the situation, economic mistakes are no doubt being made (cf. Kevin Wilson, 2016), and they could easily have serious consequences. Perhaps worst of all is the fact that rather than repudiate the failed fiscal and monetary policies that came in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis, we are collectively doubling down on them (cf. Kevin Wilson, 2019a; cf. Kevin Wilson, 2020a). This possibly won’t turn out well in the long run, although it might fend off a depression in the short run. To me, the real question is whether this “rescue package” spending will actually prove effective, or merely delay our economic destruction by a few weeks or a couple of months.

A critical question worthy of an intense national debate is the one raised by President Trump recently: at what point is our reaction to the pandemic fatal to our economy (cf. Quentin Fottrell, 2020), thereby perhaps producing more ultimate human tragedy than the pandemic alone could have? This does not imply that we should abandon our current quarantines, lock-downs, and self-distancing protocols. Rather, it suggests that at some point we will have to make a judgement call as to when to return to “normal,” because protection against the pandemic cannot be perfect, and economic damage is rapidly mounting towards deep recession-level surges in unemployment, and depression-level declines in business revenues, productivity, and GDP (cf. Kevin Wilson, 2020b). So there will be a point where we may decide that we have to strike a careful balance between community health and the economy. Achieving that balance will be as difficult as the metaphor in my title for this article (moving a piano on a spiral staircase).

Many will think that this is a fairly mean-spirited debate to have, or that we can’t possibly consider a national triage decision when many might die as a result. But medical triage is unavoidable in some situations, and it is already being done in Italy, Spain, New York, New Jersey, and other places where local surges in coronavirus patients have overwhelmed the hospitals (Matt Stieb, 2020; Edward Helmore, 2020). This is what the phrase “medical disaster” often entails, and yet it is not unreasonable to suggest that at some point the government-directed destruction of the economy has such dire consequences (i.e., the economic ruin of the country) that it must stop if American society is to survive. Integral to such a decision will be an analysis of the actual mortality rates being experienced, but media reports on this are all over the map due to their unscientific and often hysterical (or at least click-baiting) reporting (e.g., Jack Kelly, 2020). This will be discussed further below.

With regard to the economy, there is even more at risk than just the short-term functioning of the economic engine due to the damaging impacts of unemployment, etc. As I have mentioned before on several occasions (e.g., Kevin Wilson, 2019b; Kevin Wilson, 2019c) fiscal policy has long been out of control, and this crisis will push it to an even more extreme limit. Washington seems to believe that there are no consequences to our ever-expanding federal debt overhang, in spite of abundant evidence to the contrary (cf. Kevin Wilson, 2018a; Kevin Wilson, 2019d; Van R. Hoisington & Lacy H. Hunt, 2019a; Van R. Hoisington & Lacy H. Hunt, 2019b).

The Federal Reserve has long acted as the chief enabler of fiscal profligacy, with severe consequences for the Middle Class (Kevin Wilson, 2018b; Kevin Wilson, 2018c). There are alternative policies and reforms that could be useful in turning the American economy away from the Japanese-style (or even Argentine-style) abyss it will someday fall into, but these are rarely even discussed, and there has certainly been little appetite for reform in any Congress or Administration for many years now (cf. Kevin Wilson, 2018d). We have in effect created a fourth branch of government in the Fed, only this one is not subject to any real checks and balances. A toothless and pathetic Congress has played no significant role in providing those greatly needed checks and balances, and the result is a Fed that runs economy-scale experiments at our collective expense, with hardly a peep from Congress (e.g., Kevin Wilson, 2018e). If this was a severe problem over the last 12 years, as I think it was, how much worse will it become in the months and years to come?

Measuring the Risk from the Pandemic, and Implementing a Response

I am not a physician, so I won’t presume to know in detail what the scale of risk that we face from the pandemic might turn out to be. However, I am a scientist by training and I know some things about evaluating risk. So I will let the medical experts delineate the ultimate mortality and morbidity rates and run their models projecting the peak levels of contagion, but I still have questions. Why do the media insist on reporting raw mortality rather than rates of mortality (cf. Alan Reynolds, 2020)? We hear that the US has the most cases in the world, but not as often that the Italians are far worse off because they are a much smaller country. We get daily (even hourly) updates on the total number of cases and the cumulative deaths, but almost nothing at all on the preliminary rates of death. This is not that hard to figure out, and it is far more useful than just a tally sheet of the dead.

For example, Fox News reports (Fox News Blog, 2020) that as of 8:00 am on 4/01/2020, there have been 858,785 global cases, with 42,139 global deaths; this yields a preliminary global mortality rate (on those testing positive) of about 4.91%. For the US at the same time and date, there have been 189,035 cases with 3,900 deaths; this yields a mortality rate (on those testing positive) of about 2.06%. This is very encouraging news on a relative basis about the US pandemic, at least so far. But it is useful to also look at population-adjusted rates. For example, Italy has suffered 105,792 cases and 12,428 deaths in a population of 60.32 million. This yields a population-adjusted known infection rate (so far) of about 0.18% for Italy, with a population-adjusted mortality rate (so far) of about 0.02%. Of course, many who are ill have not been tested, so the number of cases must be far higher than reported (and thus mortality rates for those with the disease far lower). However, preliminary mortality rates as a percentage of the entire population are real, although no doubt they will drift higher over time, as they have in previous pandemics. In fact, there are recent reports that the Italian mortality rate is far higher than reported due to a lack of tests on many deceased patients (Dmitry Zaks, 2020).

Likewise, in the US, the population is about 331,605,440, so the preliminary population-adjusted infection rate (on those testing positive) is about 0.06%, or about one-third of that in Italy (so far). These numbers are rising very rapidly however, so infection rates will increase in the US over time. But the US population-adjusted mortality rate (so far) is only about 0.001%, or a tiny fraction of the Italian rate to date. The COVID-19 Pandemic is a dangerous one, but so far it is not the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918-1919 (which killed 670,000 Americans), nor is it the Cholera Pandemic of 1832-1849 (which killed 150,000 Americans when our population was a fraction of the size it is now; cf. Wikipedia, 2020). In fact, these preliminary rates for COVID-19 compare favorably (but only so far) to the 61,000 US deaths from influenza in 2017-2018, with a total of 21 million seeing a doctor. The latter (influenza) data yield a 0.29% mortality rate by this reporting-sick measure, and a 0.02% population-adjusted mortality rate. So yes, the coronavirus pandemic seems on a tested-patients-only basis to have a far worse mortality rate than the common flu, but on a population-adjusted rate is (so far) considerably less deadly than the media have suggested.

One of the early pandemic models generated by an epidemiologist suggested that the UK might face 510,000 deaths from this pandemic, and further suggested 2.2 million deaths could occur in the US (cf. Breanna Edwards, 2020) if nothing much was done. However, the British epidemiologist (Neil Ferguson) who predicted these massive mortality rates has since corrected his model based on new data regarding social distancing and lock-downs, and has therefore lowered his mortality estimate for the UK to only about 20,000 (James Varney, 2020; WSJ Editorial Board, 2020a); a very sad outcome, but far less scary than his original estimate.

This implies a revised American death toll of about 86,000 rather than the worst-case 2.2 million. Recent estimates by the White House team indicate a range of 100,000 to 240,000 deaths for the US. Needless to say, however, in local areas where hospitals are overwhelmed, the mortality rates will locally be far higher than the national average, so we certainly cannot afford to be sanguine about the risk. Quarantines, lock-downs, and social distancing will remain important to survival in many communities around the world for some time yet, just as they have been in other pandemics (Nina Strochlic & Riley D. Champine, 2020).

Contrary to many media opinion pieces disguised as “news,” the US was amongst the very-best prepared countries for a pandemic, according to a study released recently by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (Gregg Re, 2020). But that is a relative measure only; indeed, it does not indicate out-performance in the actual crisis. So the Johns Hopkins study does not indicate that our preparation was fully adequate for what we now face. Nor does it imply that the decisions made at the national and state level have all been optimal; indeed, the delays in reaching certain conclusions about lock-downs, equipment orders, etc. have been very costly in the short run. There are also local governments that are exceptions to the case with respect to preparedness, or that have made poor decisions from time to time that have made things worse than they had to be. Cities like New York and Los Angeles, and states like New York and Michigan have sometimes claimed that the federal government has utterly failed to protect their citizens, but their own records in the early going were not exactly exemplary.

There are indeed significant shortages of critical equipment like ventilators in some of the worst hotspots, and this is (or will be) almost certainly costing lives. How this could have been avoided (when each ventilator unit for an “ICU” costs $45,000 and a startling 25,000-30,000 units have been requested by New York alone) is never stated. Everyone is learning things from this crisis, and it will be much better the next time around. But certainly it now appears that even the “CDC” was way behind the curve on some aspects (e.g., testing kit and ventilator stockpiles) of its preparation for a pandemic (Mike Shedlock, 2020; Tom Frieden, 2020).

The White House acted decisively on travel bans but did not do very well (in the early stages) on gearing up with respect to personal protection equipment for first responders and medical personnel. Still, claims that federal aid to states like New York has been minimal do not always hold up under close inspection (WSJ Editorial Board, 2020b). Also, some mistakes were made at the state level as well, including New York’s decision not to buy 16,000 additional ventilators (deemed to be required by health officials) back in 2015 (Kristinn Taylor, 2020). And there was also California’s huge stockpile of 21 million N-95 masks that had all unfortunately reached their expiration dates before the pandemic hit (Mathias Gaffni, 2020).

Some of the politicians screeching the loudest about federal-level failures are not in any position to throw stones (not that this has stopped them). For example, the timelines for pandemic responses produced from reliable sources (Jim Geraghty, 2020) indicate that even after the virus was detected in New York City in early March, the mayor (Bill de Blasio) and the state governor (Andrew Cuomo) were counseling against fear and recommending that people continue to conduct business as usual. They later pivoted to a much better course and their more recent actions have been far more effective. But they have also tried to deflect criticism by blaming much of the problem on President Trump or the federal government.

This is actually a pretty common national, state and local response to the outbreak (i.e., playing the blame game), because many politicians are under tremendous pressure and very many were not ready for this kind of pandemic-driven onslaught. On the national level, major figures like President Trump were at first grossly over-confident that things were under control and that nothing really big would happen in the US. Again, timelines show that the president reversed course fairly quickly after initial errors, and then gradually moved to a whole series of useful emergency actions (cf. Deroy Murdock, 2020). In fact, one of Trump’s first actions was to ban travel from virus-afflicted countries; this was widely criticized as racist by the media, but it is now the international standard (cf. Victor Davis Hanson, quoted by Victor Garcia, 2020).

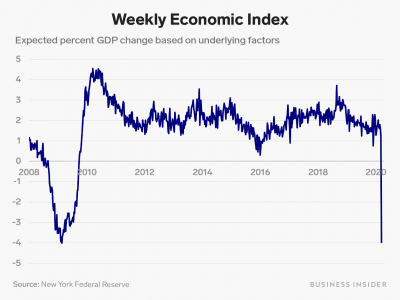

Aside from partisan bickering, the collective response by national, state, and local governments has greatly improved over time, and as a result it has now diminished the risk and improved our treatment capabilities. Again, the national death toll may still reach 100,000-240,000 (or more) according to Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Ursula Perano, 2020), based on current models (e.g., Chart 1). Recall that this model result is less than 10% of the number suggested a month ago based on Neil Ferguson’s models. It is also a population-adjusted potential mortality rate of 0.03-0.07%. This is terrible and tragic, but in a typical recent year we lost 64,000 to the opioid crisis, 61,000 to the seasonal flu, 38,000 in traffic accidents, and 47,000 to suicide; this is an aggregate loss of 210,000 under what must be called “normal” conditions, and we didn’t shut down the economy for it. Don’t get me wrong, this COVID-19 pandemic is different than any of these other tragedies and it is potentially far more deadly, unless we practice social distancing and quarantine for a few more weeks. But let’s try to keep a sense of proportion, because in 1918 we lost 670,000 from a far smaller population, and yet we survived and our economy recovered.

Chart 1: Revised US Deaths Per Day Model Projected to Peak April 15, 2020

The Economic Sudden Stop Is Tremendously Dangerous

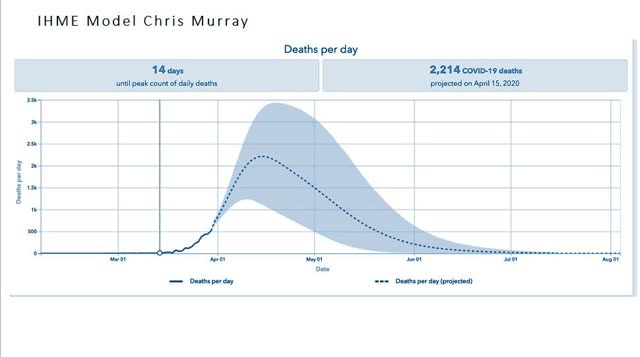

There is some fairly intense debate about whether full application of quarantines, lock-downs, and social distancing to the level of a full shut-down of the economy is necessary in every location (e.g., Ann Saphir & Jeff Mason, 2020; Marcus Walker, 2020; Ronn Blitzer, 2020). Countries such as Iceland and South Korea have managed to control (cf. Chart 2) the pandemic’s spread (so far) without resorting to full economic shut-downs (The Economist Blog, 2020; Seema Prasad, 2020). The key in both cases appears to involve massive testing relative to the population, and careful tracking down and isolation of previously unidentified disease vectors (spreaders). The US, Italy, Spain, and China all started their respective campaigns against the pandemic with far less than adequate testing capabilities. So far, it appears that as testing and isolation of the potential spreaders increase in any one society, the pandemic eventually peaks (with a lag).

Chart 2: The Goal in “Defeating” the Pandemic Is to “Flatten the Curve”

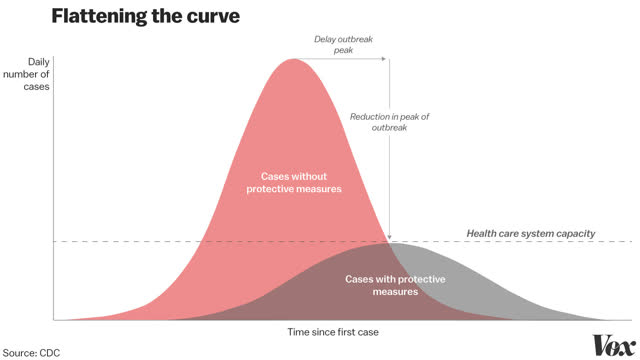

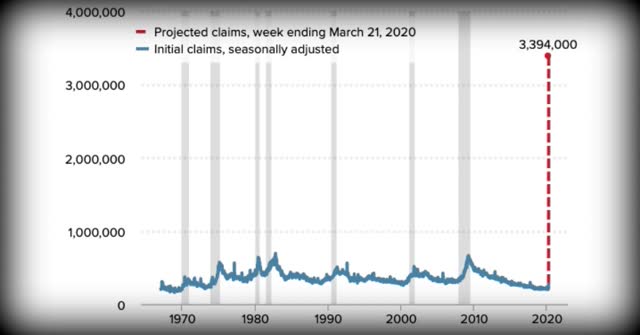

The economic sudden stop being experienced around the world is hitting the US especially hard, and it has produced perhaps the steepest descent into recession ever observed (e.g., Charts 3 & 4). This should scare most people a lot, because it is just unprecedented (cf. Stephanie Landsman, 2020). Indeed, healthy people who are practicing self-distancing and washing their hands a lot may find that they have survived the pandemic only to be severely tested by a recession of surreal suddenness, depth and severity. Those who mention the possibility of a Depression 2.0 if the lock-down continues for very long, are not in fact being unreasonable (W. E. Messamore, 2020). This dire result can only be avoided if we exit the economic shut-down relatively quickly. No economy can survive an unemployment rate greater (i.e., 32%) than that of the Great Depression (i.e., 26%) for very long; yet that is what some economists are now projecting we will see (Carmen Reinicke, 2020). The authorities thought they were shutting us down for only a few weeks, but there is abundant evidence now that the pandemic is far worse than they initially thought it would be (even if it is far better than some models projected), and it could last far longer than many initially expected.

Chart 3: Sudden Economic Stop Reflected in Weekly GDP Model

Chart 4: US Initial Claims Soaring Under Lock-Downs

This all suggests that a very difficult and politically sensitive economic decision is looming on the horizon. It will involve the kind of balancing act it takes to move a metaphorical piano on a spiral staircase. It is essentially going to rely on national-scale (and perhaps ancillary regional-scale) cost/benefit analysis (cf. Holman W. Jenkins, Jr., 2020). This approach should have been used in advance, but we are where we are, so it must now be applied on the fly. A significant mistake with regard to balance here would have catastrophic impact on our metaphorical piano (i.e., the economy). But it could also have severe impacts on the health of those (workers) carrying the metaphorical piano (economy), because an all-clear signal on the virus danger, if given too early, could lead to a second and very deadly wave of pandemic, much as was seen in 1918. Dr. Thomas Inglesby of Johns Hopkins (quoted by Ronn Blitzer, 2020; Op. cit.) has suggested that five conditions must be met before we can relax our social distancing regime: 1) regional case numbers decline; 2) full diagnostic capability is in place at clinics for a major part of the population; 3) personal protection gear for medical staff are in abundant supply; 4) ventilators, “ICU” beds, and other hospital equipment for patients is adequate to cover demand; and 5) we have the capability to identify, track down, and isolate spreaders.

President Trump and the respective governors of the fifty states (plus D.C. and the territories) are going to have to make this call (regarding balance between community health and the economy), each in their own turn, with: 1) inadequate data and thus significant uncertainty; 2) huge pressure from interest groups; 3) massive and critical scrutiny from the media and concerned citizens; 4) crushing time pressure; 5) powerful personal emotional reactions to the death toll; and 6) obviously very high political stakes. It is entirely possible that under these conditions they will muff parts of this call, or even completely miscalculate. However, it is also possible that they will get it approximately right. The decision will become easier if we reach peak contagion in just a few more weeks, and much harder if we don’t. Hopefully the president and various governors are familiar with cost/benefit analysis (cf. F. John Reh, 2019) and will be given the benefit of sophisticated advice on the subject. No physician can provide an answer for the entire question at hand, and economists will also have their limitations.

It is perhaps the biggest collective judgement call to be made in several decades. Hopefully, the welfare of the nation and of the respective states will be uppermost in the minds of our leaders. As Woody Allen once said,“ More than any other time in history, mankind faces a crossroads. One path leads to despair and utter hopelessness. The other, to total extinction. Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.” I believe that we will come out of all this in good shape, and I base that belief on the fact that our deeply divided country is starting to pull together in order to beat the common foe. We just need to stay focused and follow through in a cooperative effort to do our best. If we do, we will achieve the balance we need for this great turning point.

Conclusions

The US and much of the world face a critical question of balance with regard to the defeat of the current pandemic on the one hand, and the preservation of an already-damaged and reeling economy on the other hand. There is reason to believe that the current, massive shut-down of the economy is unsustainable, and therefore it won’t continue for very long. When it ends we will gradually return to our normal lives, obviously with some changes in place, but nevertheless very familiar to us. We will be facing massive debt problems, and we will need to investigate several major reforms to our system, both in healthcare and in economics. But we will also have a chance to improve the future and make a profit from the much cheaper stocks available in markets today.

As I’ve already suggested (Kevin Wilson, 2020c), the energy sector looks very good as a value and dividend play. This sector has under-performed very substantially in the present market crash. Energy companies have naturally taken enormous hits, and Exxon Mobil Corp. (XOM), Chevron Corp. (CVX), ConocoPhillips (COP), BP (BP), Royal Dutch Shell PLC (NYSE:RDS.B), Total SA (TOT), Occidental Petroleum Corp. (OXY), Schlumberger Ltd. (SLB), and Halliburton Co. (HAL) have all fallen well below their 2008 lows. I don’t know exactly where the bottom will turn out to be, but these are bargain prices and they represent the proverbial “Fat Pitch” baseball analogy that Warren Buffett likes to talk about. Those who like to buy low and sell high should swing for the fences at this opportunity. I have already done so myself, because as a long time oil man I know what the cycle will bring, even if I don’t really know when it will bring it. Dollar cost-averaging your way into some or all of these names makes sense over the next few weeks or months, based on valuations alone. Relatively high dividends are also attractive, although some of these will be (or have already been) cut back significantly. Even 50% cuts to dividends would still leave many names with very good yields.

I also like the mining and materials sector, which has taken an enormous hit in the current sell-off. For example, Rio Tinto Group (RIO), a diversified global-scale mining company, has suffered a draw-down of -69%; it is priced below all reasonable valuations of its cash flows or earnings. The large and diversified chemicals firm LyondellBasell Industries NV (LYB) has suffered a draw-down of -70% from its all-time high and is priced well below meaningful valuations of its long-term cash flows or earnings. The well-run steelmaker Nucor Corporation (NUE) has suffered a draw-down of -62% from its all-time high; it too is priced far below any reasonable valuation of its cash flows or earnings and is very close to its 2008 low. The large Australian-based mining/oil company known as BHP Group (BHP) (the old Broken Hill Properties) has seen a draw-down of -68%; it too is priced well below any meaningful valuations of its cash flows or earnings.

Right now, it may also make sense (with all the uncertainty, deflationary trends, and negative real rates) to invest some money in a gold fund like the iShares Gold Trust (IAU). It is a gold ETF that may be safer than some, for those who want to hold it for a somewhat longer period of time. But the safest form of gold in the event of a true financial apocalypse is physical gold. Silver (iShares Silver Trust (NYSEARCA:SLV)) looks very promising after its recent fall, but that fall was somewhat unexpected, so some caution is likely required until a more positive trend is established.

Disclosure: I am/we are long XOM, CVX, COP, BP, TOT, RDS.B, NUE, RIO, BHP, LYB, SLV. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: Disclaimer: This article is intended to provide information to interested parties. As I have no knowledge of individual investor circumstances, goals, and/or portfolio concentration or diversification, readers are expected to complete their own due diligence before purchasing any stocks or other securities mentioned or recommended. This post is illustrative and educational and is not a specific recommendation or an offer of products or services. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance.

Be the first to comment