Iurii Garmash/iStock via Getty Images

This winter – like many before it – has seen natural gas price spikes in many different geographies across the United States. The Northeast in particular has finally just seen pricing tone down a bit after cold weather gripped the area, a situation that any unhedged producers selling there would have benefited from. However, those price paradigms are short term in nature, and what is perhaps more important for longer term pricing spreads in Appalachia is what happens with Mountain Valley Pipeline. The Equitrans-fronted pipeline is the only pending major expansion project left for increasing production out of the Marcellus – and likely the last ever. Without it coming into service, Appalachian gas production will never increase from current levels. Given that tight pipeline capacity often leads to wide differentials between regional and Henry Hub pricing, how should investors interpret currently benign futures spreads?

Current Pipeline Capacity

Marcellus and Utica shale gas production has exceeded in-basin, local demand since 2014 or 2015 – a reality that set in quite quickly after drilling took off in the region. This means that producers in the area are reliant on long haul pipeline takeaway solutions to move the gas elsewhere where there is physical demand. Between 2015 and 2019, the pipeline buildout had been swift, with the region adding more than 10.0 Bcf/d of new egress capacity – capacity that was quickly filled as the largest producers put more drilling rigs to work, completing thousands of new wells.

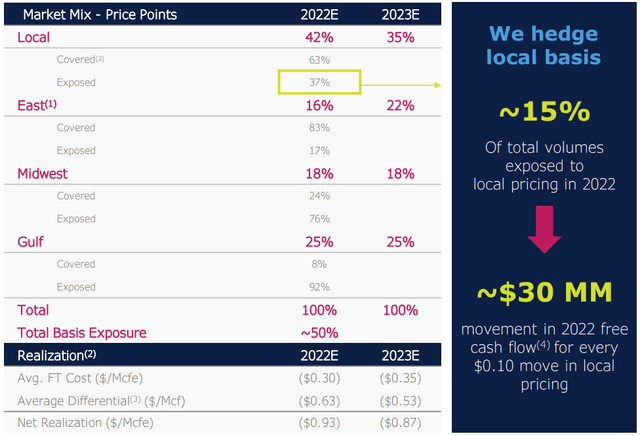

Since 2019, the only material recent increase has been the expansion of Leidy South which added nearly 0.6 Bcf/d of takeaway, ramping what could be brought into the much larger Transco system out of Pennsylvania. That capacity has been gobbled up, and now there is around 0.4 Bcf/d of spare availability; outbound solutions are now effectively 95.0% full. In the past, tight situations like this lead to a collapse in regional basis, which is a big issue for producers like EQT Corporation (EQT) and others. As shown below, the company sells quite a bit of its gas in local markets. Notably, the 2023 figure of 35% includes the assumption that Mountain Valley Pipeline will be in service. If the project is mothballed completely, that share increases back towards that 45% level.

EQT Corporation (Investor Relations Website)

This is a big deal, because natural gas sold in local markets typically receives $0.75-$1.00 per mmbtu discount to Henry Hub. This is especially true in shoulder seasons because natural gas demand falls when electrical and heating demand wanes, leading to overruns in local storage. The headache of selling gas locally is somewhat offset by lower gathering, processing, and transportation (“GP&T”) costs, but this reality is why Appalachian producers frequently report realized prices far below what many might expect if they just follow the NYMEX Henry Hub benchmark.

Mountain Valley Drama

Mountain Valley Pipeline would add 2.0 Bcf/d of capacity – likely incrementally more over the long term if partners decided to utilize increased compression to bump throughput. Once in service, this would provide an outlet for gas currently being sold locally to higher demand markets in the Mid-Atlantic. That means lower in-basin differentials all else equal, and it’s no surprise that producers that sell a large amount of gas locally quickly signed up as prospective shippers.

On January 25, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated federal permits issued from the US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management that are necessary to cross through a short three mile stretch of Jefferson National Forest. This is the second time the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals have done this, with the last event occurring in 2018. It’s a heavy blow, particularly since federal agencies have been re-jigged since these reviews were done and tilt more to the left since Biden was elected. I’ve covered this saga in detail privately on my Marketplace service, but suffice to say what matters right now is that Mountain Valley 1) has been delayed yet again and 2) the market is pricing in a higher risk of potential project abandonment. Without getting too political, this issue – cost versus stonewalling pipeline projects – is becoming an issue in the United States, something that EQT Corporation management spoke about during its most recent conference call:

And really just to read through of how important pipeline infrastructure is in this country, specifically MVP. Listen, two weeks ago, we got a letter from senators in New England saying that they’re basically looking for more supply into their areas. And the reason why they’re looking – while they’re paying extreme prices in New England is because of lack of pipeline infrastructure, plain and simple… And this is something that people need to be aware of because, what’s happening in Europe, what’s happening in New England is – it starts with things like that’s happening right now with MVP in the southeastern part of the United States

Regardless, with the permits vacated this pushes out Mountain Valley Pipeline in service to at least the middle of 2023 – if not later. Equitrans has maintained it will not do much heavy final construction during the winter months, which means the goal is for the venture to get its permits all in hand by the end of this year; meeting the prior Mid 2022 target is now impossible in my view. This puts Marcellus and Utica producers in a pickle, unable to ramp capacity to take advantage of higher gas prices available elsewhere. Local pricing basis often acts like what investors have seen in short squeeze situations in the market. It only takes a few poor decisions by moderately sized producers to blow out realized pricing differentials for everyone.

The Caveat: Flexing Production

Today, the six largest producers in Appalachia are EQT Corporation (EQT), Chesapeake Energy (CHK), Southwestern Energy (SWN), Antero Resources (AR), Coterra Energy (CTRA), and privately held Ascent Resources. These companies control roughly two thirds of all natural gas production in Appalachia, a figure which is up from a little more than the roughly half of production controlled by the big players in the region in 2015. There has been even more consolidation in the top fifteen or twenty.

During the pandemic, producers took the unique approach of pre-emptively shutting in wells in the summer and fall during injection season, ensuring that inventories did not get out of hand as liquefied natural gas (“LNG”) terminals started to see cargo cancellations and storage began to get ahead of itself before winter withdrawals would begin. Prior thought was that choking or just temporarily shutting in wells like this would damage overall ultimate recoveries from the well. It just was not done for onshore shale wells.

Admittedly, basis did end up blowing out during this period anyway. But the pandemic was a unique case, and the situation was not as bad as the basis blow-outs that occurred in 2016 and 2017. If Mountain Valley does get delayed or cancelled permanently, these kinds of actions could become way more common from the largest producers to prevent pricing problems from getting out of hand.

Takeaways

The Northeastern United States has always had a contentious relationship with the oil and gas industry. Consumers and politicians in the region have often been staunch opponents to pipeline infrastructure yet at the same time are quick to complain about electricity pricing. That is not surprising given the region averages double the price per kwh compared to major gas producing states like Texas, Colorado, or Louisiana or states that have been more supportive of building out pipeline infrastructure.

Assuming that does not change, Marcellus and Utica shale will continue to be production constrained by gas takeaway capacity – especially if Mountain Valley Pipeline cannot get across the finish line. If that becomes the case, the major producers in the region will likely have to throttle and manage production to keep basis from getting out of hand. For now, basis futures have not blown out, but my worry is future delays on Mountain Valley will make it difficult to hedge at reasonable rates this time next year.

Be the first to comment