Sky_Blue/iStock via Getty Images

Investment thesis: Cheniere (LNG) is thought to be among the best-placed LNG producers that can take advantage of the geopolitical need to replace Russian gas supplies to the EU, with other sources such as LNG. The US LNG industry, born on the back of the shale revolution has experienced a massive expansion over the past years, with US LNG exports volumes set to reach the number one spot globally. There are however some significant headwinds that may put a damper on Cheniere’s long-term expansion prospects, as well as its profitability. Shale production is stagnating. The current political environment is mostly hostile, with recent signs that the current administration favors environmentalist considerations over geopolitical and economic needs. Non-governmental entities are putting pressure on the oil & gas industry. They recently attacked LNG expansion plans by insisting that banks should cut off all financial support for new LNG projects, as well as expansion projects at existing facilities. Cheniere just recently signed a contract to build seven new trains, with a total LNG producing capacity of over 10 mtpa. With all the challenges facing this new project, Cheniere may have a hard time bringing it to completion, even though geopolitical and global market realities make it a perfectly sound project.

While the EU pledged to completely replace Russian hydrocarbons by 2027, the Biden administration, as well as environmentalist lobby groups, are getting in the way of building up hydrocarbon export capacities needed to help them out.

Within the context of a global commodities bull market, the EU decided to completely break with the world’s largest net exporter of hydrocarbon energy. The EU is currently Russia’s most important export market for those energy supplies. The EU imports about 150 Bcm of Russian gas per year, which comes out to slightly more than the entire LNG capacity that the US is set to reach this year.

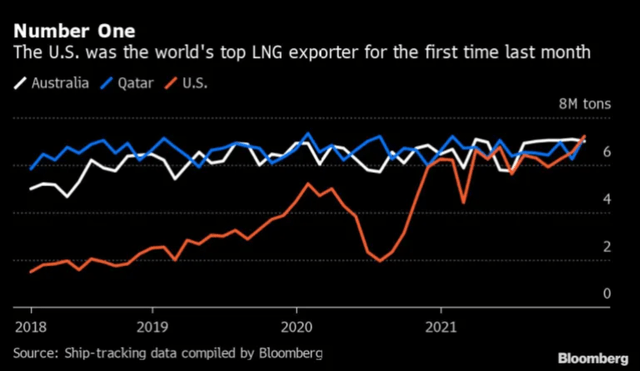

US, Qatar, Australia LNG exports (AlJazeera)

As we can see, US LNG exports reached about 7 million tons/month recently. Assuming that it will keep up that average pace this year, it will export about 120-130 Bcm of natural gas. About half of it has been going to the EU lately, as an effort to relieve the pressure on its market, with most of the rest headed to Asia. If most of the rest of the US LNG exports could be diverted to Europe, it would meet about one-third of the Russian natural gas substitution goal in Europe. Other sources of LNG could be found as well, which could go a long way in helping Europe meet its strategic goals. It goes without saying however that realistically speaking, the world cannot divert the bulk of all LNG to the EU. Capacity expansion will have to play a big part in it, and the US will have to do its part if there is to be any significant progress made on this plan.

As I already pointed out, the Biden administration has reportedly nixed a plan to coordinate a push to export more LNG to the EU in order to enable member states to reduce their reliance on Russia. This comes even as the EU put forward a plan to end all fossil fuel imports from Russia before 2030. The EU plan is itself not a complete substitution plan, but rather a combination of drastically cutting fossil fuel demand and substituting wherever it may be possible to do so, with resources from elsewhere. It is therefore not like allowing for more US LNG exports to the EU is enabling a bad actor in terms of emissions. The EU’s long-term goal remains net zero emissions by 2050, meaning that Europe’s growing reliance on US LNG supplies would in theory not be a permanent phenomenon.

With banks potentially poised to not extend Cheniere a credit line in order to facilitate the building of the trains, the financing of the project could be in peril. Stock issuance or offering of bonds may have been a way to raise money in the past, but with more and more institutional investing entities abiding by ESG guidelines, it is becoming increasingly difficult for companies involved in the oil & gas industry to raise money that way. Getting the funds to pull off this expansion project is going to be potentially difficult. Perhaps not so difficult as to derail this project altogether, but difficult enough that it may cause significant delays.

Upstream producers are faced with very similar issues. First and foremost, there is the often-ignored depletion of US shale prime drilling locations. This is a factor that can have a very high impact on US LNG because LNG producers need to have as wide a gap as possible between US natural gas prices and the price that is paid in Europe or in Asia. US LNG producers need to pay for the gas in the US, then come all the costs involved in liquifying it, shipping it, and then re-gasifying it. On top of that, ideally, they would like to make a profit.

If upstream producers will have to increasingly drill second-tier acreage, they will only do it if the price of gas will cover the extra costs of producing from lower-quality reserves. This could squeeze LNG profit margins. In a worst-case scenario, LNG producers could be deprived of the volumes of gas they need to feed the infrastructure they built into place.

Just how much prime acreage there is left in the shale patch is subject to debate, and the facts generally tend to reflect the pre-existing bias of those arguing one way or another. I cannot pretend to not have any pre-existing bias of my own. From the early days of my coverage of the shale industry, I found plenty of evidence as I studied company presentations in regard to oil & gas well results that suggest there is plenty of second-tier acreage in most shale fields, with only a small fraction of each field being economical within a price range that is lower than the price we think we need to reach before demand destruction starts to kick in.

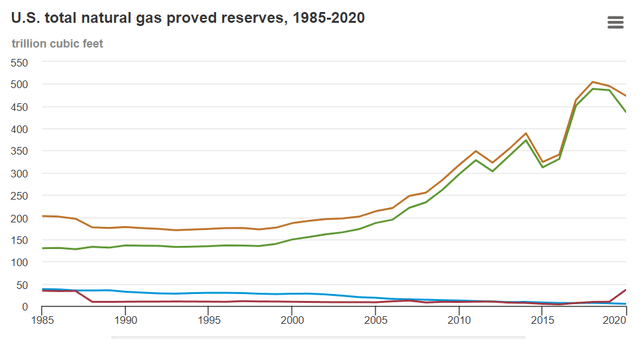

Keeping in mind the fact that I may be biased in looking at data points that reinforce my own pre-existing views on shale, I find that one of the most telling data points in regard to US natural gas reserves is the evolution in reserves from 2018 to 2019.

US natural gas reserves (NYSEMKT:EIA)

From one year to the next, US reserves declined by about 2.5%, while every year the US produces about 7% of its total reserves. In other words, reserve replacement amounted to about 2/3 of the volumes produced. What this tells me is that given the average price levels seen in past years, we will not see a very significant upgrade in reserves. In other words, we need to see steadily rising prices in order to see reserve additions in the long term. What this means for LNG exporters out of the US is steadily rising natural gas costs, even as other costs, such as environmental compliance, as well as rising costs of money are also set to squeeze profitability going forward.

Cheniere could finance its expansion from internal resources, but it may take a while to get it done.

Cheniere’s latest financial results suggest at first glance that the higher price of LNG last year did not help a great deal with its financial results. Cheniere closed the year 2021 with a net loss of $2.34 billion, on revenues of $15.9 billion. The net loss includes a $5.8 billion loss from derivatives, which has nothing to do with the actual profitability of Cheniere’s LNG production and selling activities. Such losses should diminish going forward, assuming that Cheniere will not pursue an overly pessimistic LNG hedging strategy.

Given the favorable LNG market at the moment, as well as for the foreseeable future, Cheniere could in theory pursue its capacity expansion strategy without having to worry about credit facilities to make it happen. It doesn’t mean that it would be easy. The easiest path for such a capacity expansion would be government support for US upstream, midstream, and downstream activities in the oil sector, in the form of common-sense regulations, as well as putting an end to certain forms of obstruction, such as limiting drilling on federal lands or obstructing pipeline construction. An end to the trend of financial institutions caving to the environmentalist lobby would help perhaps even more. At this point, the ESG trend may become an even greater threat than current government policies. Unlike government policies, the electorate does not get to have much of a say either.

While the direct threat to Cheniere’s LNG expansion plans stems from non-governmental pressures, such as the most recent efforts meant starve such projects, there are arguably far greater indirect threats to not only the execution of such a project but its future viability. In some respects, the greater threat is indirect, where geological realities, combined with government measures, as well as non-governmental pressures can combine to deny such LNG projects the natural gas it needs to source at an affordable price. In many ways, the worst possible outcome would be if Cheniere completes the expansion project, only to realize that US production is nowhere near capable of keeping up with America’s expanding export capacity. It could face higher input prices, or even government actions, such as curbs on LNG exports, meant to protect the domestic consumers, as some politicians suggested we should proceed recently. While the global market and geopolitical situation would indeed suggest Cheniere facing favorable conditions to expand profitably, it is by no means a certainty that things will work out. In fact, things are arguably rather bleak, with the risks it is facing outweighing the potential opportunities.

Be the first to comment