peshkov/iStock via Getty Images

The upstream investment environment continues to face significant pandemic- and climate change-related headwinds in 2022, despite projections of higher oil and gas (including LNG) prices.

After two years of sub-par investment and deferred final investment decisions, upstream project sanctions are needed in short order, given base case outlooks for future energy demand and the existing supply trajectory.

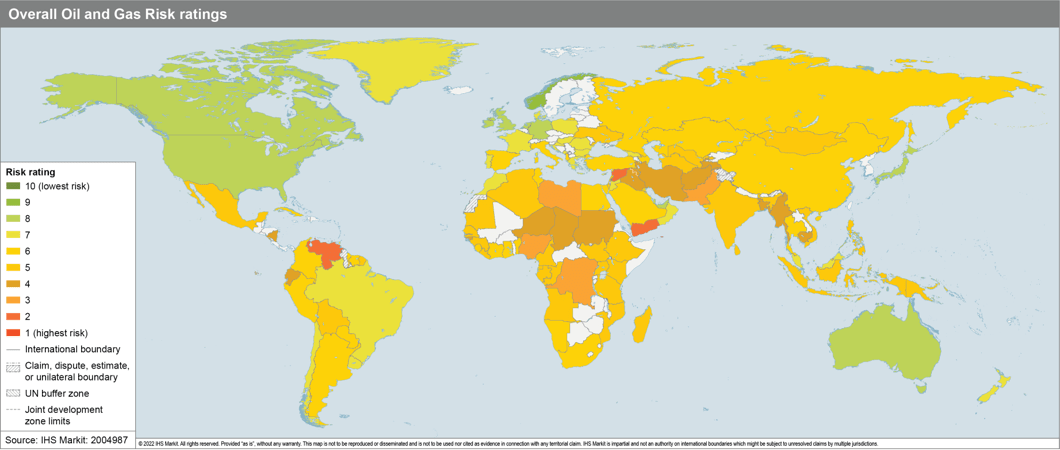

Overall oil and gas risk ratings IHS Markit

Figure 1: The upstream above-ground risk environment varies dramatically across the 118 territories rated by IHS Markit PEPS Oil and Gas Risk.

Several sometimes conflicting global and regional trends will play a role in determining the destination, project preferences, and scale of upstream spending in 2022:

- Existing global systems and diplomatic tools are proving increasingly unfit to manage geopolitical crises. Tensions between major powers will continue to drive international trade and conflict risks, including in areas with substantial hydrocarbon prospectivity and along key transit routes. Particular points of risk include US-China provocations in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea, as well as the standoff between Russia and the EU and US over Ukraine amidst the ongoing power crisis in Europe. With existing diplomatic structures and tools proving inadequate to address geopolitical issues, governments are likely to increasingly adopt new means to exert leverage, for example via cyberwarfare or control of key infrastructure and/or rare earth minerals. The result is likely to be long-running, unresolved conflicts with periodic flareups – alongside a potential for miscalculation as actors try out new approaches.

- Measures to counter the virus are likely to disrupt economic activity and demand for energy, albeit with more localised and time-bound effects than before. The ebb and flow of the COVID-19 pandemic and government restrictions to counter its effects will continue to disrupt the movement of goods and people. On the margin, this could affect supply chains for upstream projects and the deployment of personnel and equipment, albeit likely to a lesser extent than in 2020-21.

- The current accounts of oil and gas exporting countries will rebound from higher oil prices, but fiscal challenges may drive changes to E&P terms. Significantly higher oil prices in 2021 have contributed to a substantial improvement in the current account and fiscal balances of most major oil producers. However, inflationary pressures are eroding some of the beneficial impact of the rebound for some OPEC+ producers, including Russia, Nigeria, and Angola. Some changes to E&P contractual terms and risks can be expected, with those governments able to balance priorities perhaps moving to improve investment terms to help increase output (e.g., Argentina, Ecuador, Equatorial Guinea, and Trinidad and Tobago), while others may seek increased rents from the sector to raise immediate revenues (e.g., Russia).

- Inflation and lockdown fatigue increase the potential for political volatility, limiting the bandwidth for strategic policymaking and international engagement. Until now most governments have tried to counter the effects of COVID-driven disruptions on economic activity with aggressive increases in deficit spending, but that approach is reaching its limits, suggesting varying degrees of austerity ahead. Even where governing parties maintain power, immediate pressures will distract attention from more strategic domestic policymaking, for instance in adjusting approaches to oil and gas. States may also have less bandwidth to work together on global issues – including climate change and the pandemic – and pursue the sustained diplomacy needed to resolve international crises, e.g., Iran’s nuclear programme and civil conflict in Libya.

- COP26 commitments will translate into further policy and regulatory changes affecting the upstream. Countries have agreed to review their nationally-determined contributions (NDCs) as part of the Glasgow Climate Pact, which is likely to lead to more ambitious 2030 greenhouse gas emission reduction targets on the path to the net-zero goal by mid-century. While oil and gas are only mentioned in the context of ‘unsustainable subsidies’ in the actual COP26 treaty text, the need to ramp up emissions cuts means that in practice, many producer countries will likely introduce additional requirements for the upstream industry, as well as end users. Potential regulatory changes are expected to focus on minimising venting, flaring, and fugitive emissions as 111 governments seek to advance the goal of a 30% cut in worldwide methane emissions by 2030 under the Global Methane Pledge. Governments in Europe, North America, the Middle East, and Asia are likely to emphasise the deployment of carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) projects to reach carbon neutrality. This will include regulations to establish industrial hubs to link upstream facilities to CCUS projects and blue hydrogen production sites. Governments and companies will need to work together to develop credible emissions accounting and benchmarking and set targets for the sector in the context of broader national and global commitments.

- Companies face a ‘carbon dilemma’ between E&P investments and commitments to reduce emissions/diversify into renewables and low carbon energy. Listed companies will face increasing pressure to balance upstream strategy with climate concerns, forcing further scrutiny of existing operations and future portfolio choices. Resource type, sub-surface productivity, extractive methods and operator practice will come into play in differentiating between assets and company performance. Companies are also likely to closely examine incentives to electrify upstream operations as a primary way to reduce Scope 1 and 2 emissions in a cost-effective manner. The carbon dilemma may further increase the attractiveness of investment in large producing countries where historic under-investment (due to civil conflicts and/or sanctions) creates opportunities for clear and transparent ‘wins’ to lower emissions through infrastructure upgrades, associated gas capture, and the deployment of renewable power.

- Sources of upstream finance will contract further as public and private institutions redefine lending criteria on climate grounds. The formation of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) at COP26 promises to advance the role of private financial institutions in decarbonisation by promoting a common approach to lending. The alliance already includes more than 130 banks, asset managers and insurance companies responsible for trillions of dollars of assets. Increased scrutiny of emissions intensity and project carbon credentials is likely to ensue, further cutting back finance available to upstream. Public investors are already pulling back. The US, Canada and 18 other countries committed to stop public financing of foreign fossil fuel projects by end-2021, and the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the World Bank have already slashed or committed to slash funding for oil and gas, among other multilateral bodies. Importantly China, Japan, and South Korea, which provide most such financing, made no such commitments, and some financially strong petrostate NOCs including several in the Gulf will be insulated from these trends.

- The future of natural gas hangs in the balance as governments and financial institutions set out strategies and standards. The past year’s energy supply crises in the US state of Texas and then in Europe have highlighted the real-world challenges in managing an energy transition with undue reliance on renewables and infrastructure and technology that are not yet in place. Perhaps partly in response, the European Commission announced on 1 January that it sees a role for natural gas and nuclear “as a means to facilitate the transition towards a predominantly renewable-based future”, albeit its statement is not yet final. Decisions made in 2022 by governments, financial institutions, producing countries and investors will be critical in determining the role of gas energy outcomes in 2030 and beyond.

- Climate litigation will become a key instrument for environmental activists to hold governments and companies accountable for reaching emission-reduction targets. The Dutch court’s 2021 order in Milieudefensie et al. v Royal Dutch Shell (RDS.A) (RDS.B) (2019) to Shell to reduce its emissions by 45% by 2030 relative to 2019 levels is likely to encourage civil society groups to seek similar legal remedies against oil and gas companies in other jurisdictions, as well as challenge government policies on energy and climate following successful suits in Neubauer et al. v Germany (2020), VZW Klimaatzaak v Kingdom of Belgium and others (2014) and Urgenda Foundation v State of the Netherlands (2015). The COP26 commitment to “eliminate inefficient fossil fuel subsidies” could provide new grounds for challenges to country-level fiscal and contractual terms where those are seen as subsidising hydrocarbon exploration and production. In the US, civil society groups are expected to continue to pursue legal action against the Biden administration’s approval of upstream projects, questioning the validity of environmental reviews.

- E&P will pick back up in 2022, but the resumption of activity is likely to be uneven as the energy transition continues to shape company responses and investment opportunities. Viewed from a macro perspective, 2022 may look like a return to business as usual for E&P firms. Finances are improving and E&P activity will expand in North America, the Middle East, Russia, and China, as well as in highly prospective provinces like Brazil and Guyana. With yet-to-be-sanctioned oil and gas volumes accounting for roughly a quarter of anticipated supply needs in 2030, an uptick in FIDs starting in 2022 will be critical. For most countries, however, changes related to the energy transition mean that oil and gas markets beyond 2030 will likely be smaller – and more regulated – than previously expected. Given development times required to monetise new resources, approaches to exploration and development will almost certainly shift accordingly, such that producing countries with large reserves are beginning to focus on the possibility of stranded reserves. Other governments will try to remain in the game by improving the attractiveness of their terms and conditions. Differing outlooks among producing countries, regulators and investors mean that sector approaches will be highly varied, setting the stage for a year of mixed signals and heightened above-ground uncertainty.

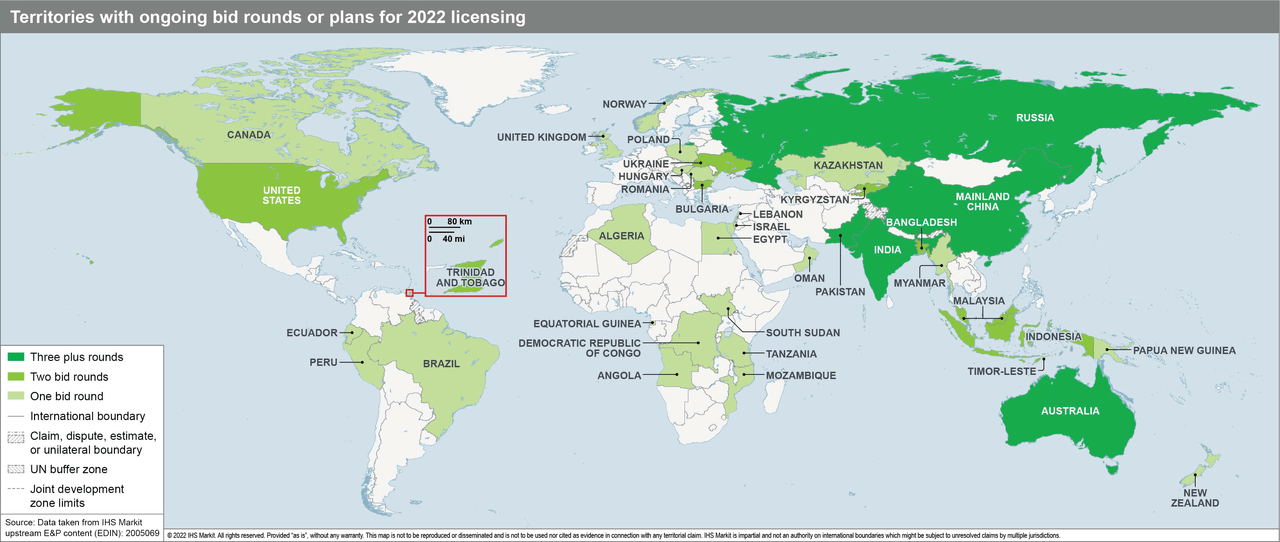

Territories with ongoing bid rounds or plans for 2022 licensing IHS Markit

Figure 2: Licensing efforts are slightly up on 2021, from 59 to 65 active and proposed rounds, reflecting the continued use of time-bound competitive award processes to promote exploration access across producing states. The use of open block award processes is rising, particularly in Asia, as governments seek to maximise a closing window of opportunity amid energy transition.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment