Your Father’s Oldsmobile MAXSHOT/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

Readers of a certain age will recognize that Oldsmobiles were sort of a “poor man’s Cadillac” for many years (along with their sibling Buicks) until General Motors (GM) stopped making them (Olds, not Buicks) in 2004. The expression “your father’s Oldsmobile,” which was applied to stodgy, boring, but dependable and serviceable products of the type that might appeal to an Oldsmobile owner, will likely also go out of use in a few years.

But until it does, I think it applies pretty well to John Hancock Investors Trust (NYSE:NYSE:JHI), one of those boringly conservative corporate bond funds that you could park in a portfolio and forget about over many years, and earn about 6% annually. At least that’s been the experience over the 34 years since it started keeping consistent performance records back in 1988. (The fund was actually started in 1971, but John Hancock’s website says the records for the first 17 years are “not available.” Go figure.)

The fund straddles the gap between (1) pure investment grade and government bond funds and (2) high yield bond funds, with 57% of its assets in the “investment grade/near investment grade” spectrum of the corporate credit market (i.e. the BBB/BB categories).

It does NOT pay a so-called “managed distribution,” a sign of a conservative fund that only wants to pay out what it actually earns or expects to earn; and has no desire to “borrow” earnings from the future and pay them out today, which can “smooth out” distributions during down-turns, but risks eroding capital if the downturn goes on for too long. (As discussed here.) That means distributions move both up and down from time to time, as capital market conditions and interest rate levels change. Recently the fund reduced its distribution by 18%, to a current yield of 7.8%, and a discount of -5.6%.

While 7.8% won’t knock the socks off typical high-yield bond investors, who are seeing yields in the 9-10% and even higher range lately, it may look pretty attractive to more traditional investment grade investors. (I hold it in our well diversified “Widow & Orphan” model portfolio.) It is important to look at the credit quality of a fund’s portfolio in deciding whether the risk/reward balance is right for each investor, since not all of us are comfortable with the same level of risk.

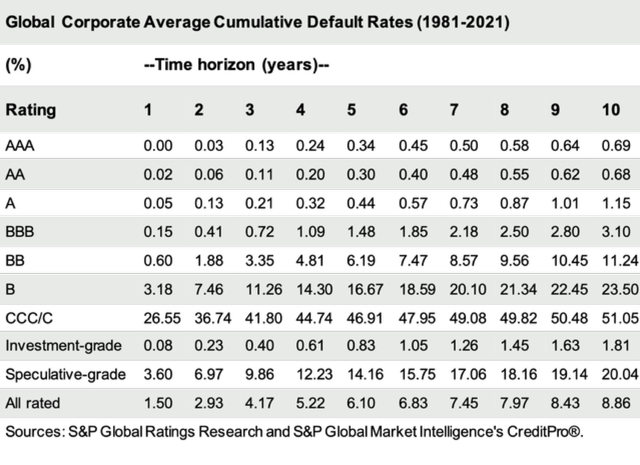

Corporate Default Rates

Here is where we get a bit nerdy. This table shows the average corporate default rates for various rating levels going back 40 years. High quality credit shops, like John Hancock, can often do a bit better than the averages, especially if they operate in the privately placed debt market where they sometimes structure and monitor their credits more closely than typical high yield bond underwriters. But for purposes of our analysis, I am going to assume that JHI’s credits perform just like the averages, no better and no worse.

The typical high yield bond fund operates in the BB, B and CCC sectors, often with a number of unrated or privately placed credits. There is quite a jump in default rates when you move from triple-B, the lowest level of investment grade credits, down to double-B, the highest grade of non-investment (i.e. high yield or so-called “junk” credits). As the table shows, over a five year period, the cumulative default rate for the BBB credits is 1.48%. For BB credits it’s 6.19%, or about 4 times as much. For single-Bs, it jumps to 16.67%, or over 2 1/2 times as much. Triple-Cs and below default at an even faster clip, with 46.9%, or almost half of them, defaulting over the first 5 years, and most of those tank in the first 2 or 3 years. Note that the rate only increases to 51% over ten years, which means the CCC and below credits that make it past the first couple years probably make out OK in the longer run.

With these default rates, along with the knowledge that similar studies have shown the average defaulting corporate bond ends up recovering, via bankruptcy or otherwise, about 50% of its principal (70 or 75% for defaulting secured loans, but that’s another topic for another article), we can project the likely portfolio credit losses for any corporate bond fund, as long as we know its portfolio credit ratings composition.

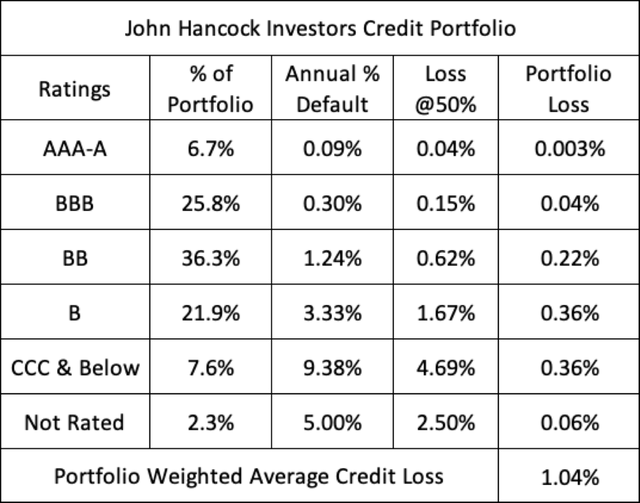

JHI’s Default and Loss Profile

Let’s do that with JHI. Here is JHI’s portfolio broken out by credit ratings. We calculate what the credit loss rate would be for each slice of the portfolio (based on its credit rating), using the average annual default rate for that rating and assuming a 50% recovery. We have assumed that the “unrated” category falls somewhere between the single-B and triple-C category, which is probably overly draconian, since many unrated credits may be privately placed bonds that John Hancock has underwritten itself and knows the issuer well. We take the 5-year cumulative default rate by rating category and then we divide it by 5 to get an average annual rate.

This shows us that if we take the average annual default projection for JHI’s portfolio of corporate credits, based on its credit rating distribution, we can anticipate portfolio credit losses in the range of 1% per annum, assuming future defaults and losses reflect the overall corporate market’s 40-year average. Experience has shown us that S&P and Moody’s corporate ratings have been pretty consistent in projecting future credit defaults and losses over time.

JHI reports that the average current coupon on its bond portfolio is 5.8%, and as we reported earlier, its annualized total return for the past 34 years has been about 6%. That suggests it has either (1) earned a higher coupon rate at various times in the past than at present, (2) offset credit losses with capital gains over time, and/or (3) suffered a lower rate of defaults and losses than the market average. Most likely a combination of all three.

As I said earlier, this suggests to me that JHI is a pretty solid fund, earning an attractive and pretty stable return (for a bond fund) while positioning itself firmly in between the investment grade and high yield credit categories.

For investors seeking that higher level of yield and return than they could get from most pure investment grade bond funds, and not wanting to embrace the higher risk/reward profile of a true high yield bond fund, it may be worth a look.

Some Perspective: Real High Yield Bond Funds

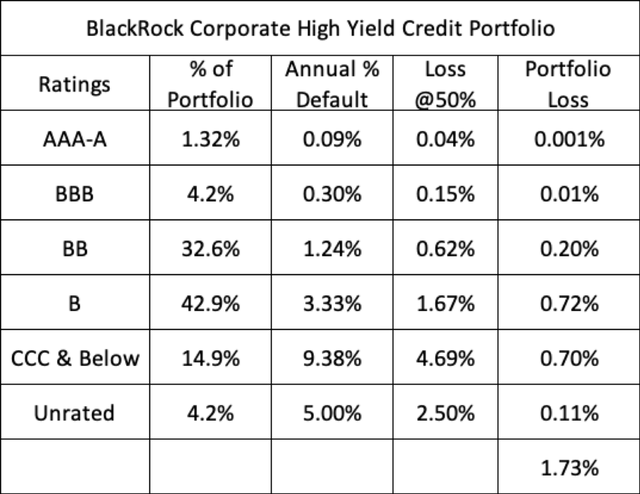

It might be helpful to some readers to compare the credit profile of an Investment Grade/High Yield “crossover” fund, like JHI, with some real high-yield bond funds. I’ve selected two of them: BlackRock Corporate High Yield (HYT) and Pioneer High Income Fund (PHT).

Here is the same table we showed for JHI, but with HYT credit quality distribution. HYT pays a distribution yield of 9.77%, with a discount of -3.6%.

Note HYT’s loss projection would be 1.73%, about 70 basis points per annum higher than JHI’s. Investors might believe they are being reasonably compensated for the higher risk, with the yield being about 200 basis points higher.

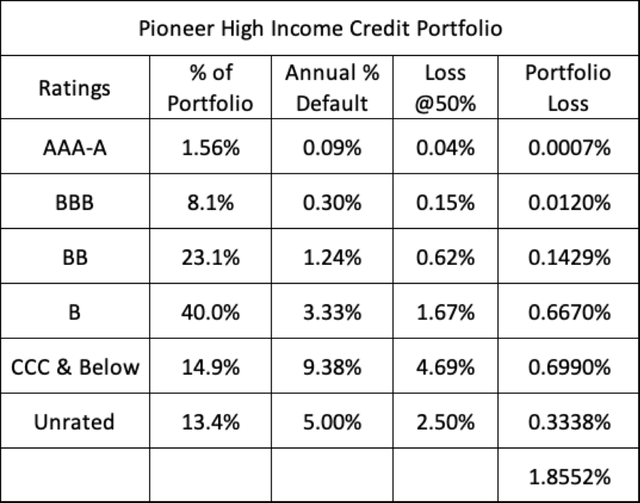

Looking at another high yield fund, PHT, we see a similar situation. PHT pays an even higher distribution yield than HYT, at 10.5%, and a discount of -9%.

PHT, with a slightly higher concentration of single-B, CCC, and Unrated, has an even higher projected loss rate, but one the market seems to be compensating investors pretty well for taking at the moment.

This suggests to us that, from a risk/reward perspective, high yield bond investors are perhaps being over-compensated for the additional risks they are taking. This is not surprising, since investors and markets often get more anxious about credit risk than the statistically predictable risk actually deserves. Randy Schwimmer, senior managing director and co-head of senior lending at Churchill Asset management, and also founder/publisher of The Lead Left, first reported a couple months ago about what he called the “worry discount” that can affect the credit markets when fears of recessions and downturns inspire discounts in loan and bond prices that are out of step with the actual likely risks of loss. Here’s what he wrote about the high yield loan market, which inspired me to write this article at the time:

“In recent months, thanks to market volatility caused by higher interest rates, toppy inflation, and the perceived higher probability of a recession, large cap loan prices have traded down sharply. S&P/LCD’s leveraged loan index has dropped from 98.5 in February to 92 last week. While an economic downturn would certainly increase the probability of loan defaults and losses, history shows that BSL (“broadly syndicated loans”) default rates barely amounted to 8% in the Great Recession, let alone losses. So at this stage in the credit cycle, 92 represents the “worry discount” from perceived higher credit risks, particularly in sectors such as energy, food and commodities.”

Conclusion

There seems to be something for everyone in the credit markets these days. Bond funds like JHI, that bridge the investment grade and high yield markets, provide serious yield and potential return to conservative investors who need real income and can’t afford to tie their assets up in asset classes so “safe” (like Treasury bonds and highly rated Investment Grade bonds) that you collect only puny yields while taking on longer-term interest rate risk than you’d ever have in a shorter term high-yield bond.

Meanwhile, high-yield bonds provide true “equity returns” without equity risk at current yields in the high single digits and beyond, for investors willing to accept the slightly higher but still manageable default and loss risks that such credits present.

Investors contemplating such high yield bond investments shouldn’t get spooked by writers and commentators who carry on about the “high risks” that such “junk” bonds present. Most of those investors already hold mid-cap and small-cap stocks in their equity portfolios as a matter of course.

They may not realize that high-yield bonds are merely the debt of those same mid-cap and small-cap companies. And since the debt has to be paid or the equity of such companies is worthless, those investors are already carrying more risk by holding the companies’ stock than they would ever be taking by buying their bonds.

I hope this is useful, stimulating and/or interesting, and look forward to your comments and questions.

Be the first to comment