airdone/iStock via Getty Images

Introduction

About a month-and-half ago, on 9/14/22, I wrote an Advanced Micro Devices (NASDAQ:AMD) article titled “Here’s The Price I’ll Start Buying AMD Stock“. In that article, I shared the investing process I use when buying really deep cyclical stocks like AMD. As part of this process, I established two buy prices for the stock, which are the points at which I am prepared to make a purchase. Here is how I summed things up in the conclusion of the article:

AMD stock peaked at a price of $164.46, which puts my first buy price at $57.56 per share, and my second, deeper buy price at $16.45 per share. As I noted above, these initial positions would be about a 1% portfolio weighting each. I have cash set aside right now that I would likely use for the first purchase, but if we do see that second buy price, I would likely raise cash from a combination of lower-beta and lower-quality positions in my portfolio that wouldn’t offer the same sort of potential upside that AMD does.

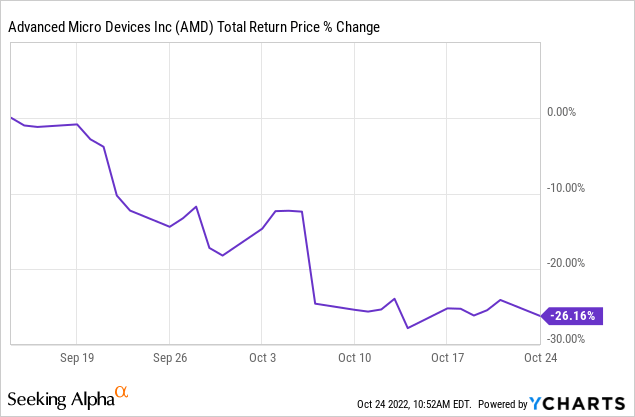

In the article’s comment section, I got a surprising amount of pushback for both of these buy prices, especially the lower one, because readers thought the prices were ridiculously low. Here is how AMD’s stock has performed since the article was published.

As I write this, AMD is trading around $57, and, as per my strategy, I have purchased the stock with approximately a 1% portfolio-weighted position, so I am now long AMD. However, I expect the price to keep falling over the next several months. This begs the question, which I’m sure many readers are asking themselves: Why, if I think the stock price is going lower, would I buy a position right now? And, I think that’s a fair question, one which I hope to answer in this article.

Because I so recently wrote an AMD article that describes in detail the process I use to establish my buy prices, and readers can simply click that link to go read the article, I want to take the time in this article to explain some of the nuances around the strategy that include broader portfolio-level considerations so that readers understand where I’m coming from and why I’m taking the approach that I do with stocks like AMD. I will also explain why I waited for such a deep dive in AMD’s stock price before buying. My hope is that AMD shareholders, and potential purchasers of the stock, will be able to improve their returns with stocks like AMD in the future.

It’s unusual to get (and stay) rich with stocks

There are certain stocks one comes across, like Tesla (TSLA), Apple (AAPL), Nvidia (NVDA), AMD, and a few others, where if an investor bought a substantial amount of shares at rock-bottom prices, after a big run-up in price, they may legitimately say that they “got rich” off of such-and-such stock. Additionally, with many so-called billionaires in the investment world, such as hedge-fund managers and other asset managers who are wealthy, it is implied that they got rich by investing in public markets. This makes it seem sometimes as though the stock market is a reasonable place for a person to “get rich”. But the truth is that most asset managers’ wealth actually comes from fees from their clients, not from the returns of their public investments. Similarly, with regard to wealthy founders, they didn’t buy the stocks they own in the public markets, which is what their reported wealth is based on. So, while there are a few fortunate investors who placed big bets on a public company that rose 10x or more, they are extremely rare and it’s very difficult to know if those investors succeeded from their investing talent or if they just happened to get lucky. I see very few investors in the comment sections of my articles who claim to have gotten rich off of such-and-such stock and also claim to have done as well with other stocks in different industries. For example, I have never heard of an investor who bought large positions in both Apple and Monster Beverage (MNST) in 2002, both of which performed phenomenally since then. This leads me to believe, their getting rich quickly in the stock market is more a matter of luck (even if the luck is being an expert in a particularly fast-growing industry at the right time) than it is part of a larger investing process that can be repeated in various industries over long periods of time.

I think this is an extremely important point to make because it will color one’s entire approach to stock investing. If you are trying to get rich and you are not already rich, you need to concentrate almost all of your money into a handful of investments, then you have to be right about most of those investments, and then usually hold them for a long time. While I won’t deny there are going to be a few people who truly had early insights into stocks like this, I think the truth is that most people who get rich investing in public stocks in less than 15 or 20 years, got lucky, which means their process isn’t very useful for the rest of us.

Because of this dynamic, if a person puts aside the goal of getting rich quick in the public markets, and instead simply wants to increase their wealth over time in a dependable way, then they need some sort of repeatable and reliable investing strategy (or combination of strategies) where the “luck factor” is minimized. The trade-off in taking this approach is sacrificing the likelihood of quick riches, which is exchanged for dependable long-term wealth creation. It’s the difference between buying a lottery ticket and buying a good business.

What this does in practical terms are two things. First, it shifts one from an overly concentrated portfolio to a less concentrated portfolio, because that reduces the effects of luck (both bad luck and good luck). Second, it means an investor can think more about the prices at which a stock is likely to produce acceptable medium-term returns, rather than trying to pick the absolute bottom for a given stock. This is a subtle, but important change in mindset because picking absolute price bottoms consistently is virtually impossible, and trying to do so usually ends up with the investor missing the bottom anyway, sometimes by a large margin. Buying at a price that is likely to produce a good return is much easier to do, especially with a stock like AMD.

For example, I bought AMD when the stock price was about -65% off its highs. Even if it takes five years for the stock price to recover its old highs, that still produces a +23.63% CAGR. That is a return that’s on par with the best investors in the world. So, as long as we like AMD’s business over the medium term, which I do, no matter how deep the stock eventually falls, this is still a very good price at which to buy the stock. If the stock price took a full decade to recover its old highs from today’s prices it would produce an +11.03% CAGR which is still above the long-term market average. There doesn’t seem to be any argument from investors that AMD is positioned well in relation to its competitors over the medium term. That means, the real question involves what the macro will be like. And while the near-term macro indeed looks horrible, technology will keep progressing and improving, and I believe the long-term secular growth demand for AMD’s products will remain intact when we look forward five years from now. So, in some sense, it’s easier to see five years into the future than it is to see six months or one year into the future, which is what the market is currently focused on. That creates opportunities for investors who are not trying to get rich quickly, but are instead trying to get extremely good medium-term returns.

There are several other semiconductor stocks that are in a similar position as AMD is right now. This means AMD isn’t the only opportunity of this type. I also recently purchased Micron (MU) using the same method I used for AMD. Nvidia is getting close to my buy price, as is Microchip Technology (MCHP), which I bought during the March 2020 downturn and turned a +140% profit on it in less than a year. So, it is going to be possible in the coming months to buy many semiconductor stocks at good prices, therefore eliminating or reducing single-stock risk. Again, this is a way to replace luck with a dependable investing process.

History is the best guide for the future

I think another reasonable question to ask about my semiconductor strategy is why I decided to wait for such a big decline in the stock of such a great company like AMD. The basic answer is that when it comes to the stocks of good businesses that are simply in a cyclical industry, history is almost always the best guide for estimating the future. In fact, when making any prediction about things that involve large numbers of social interactions (like stock prices), the best practice is to examine what happened during similar situations in the past. Humans haven’t changed much in the past 3,000 years. It’s often perfectly appropriate in life to learn from examples of ancient Greece or Rome and apply them to today. Sometimes we might have to make adjustments for technological changes or institutional changes, but basic human behavior is the same now as it was then.

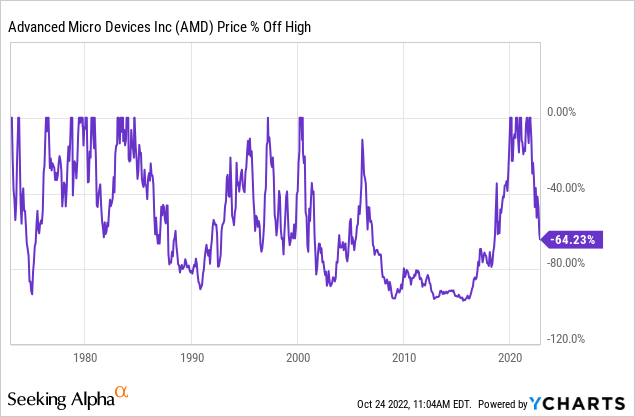

Here is a chart of AMD’s historical price drawdowns:

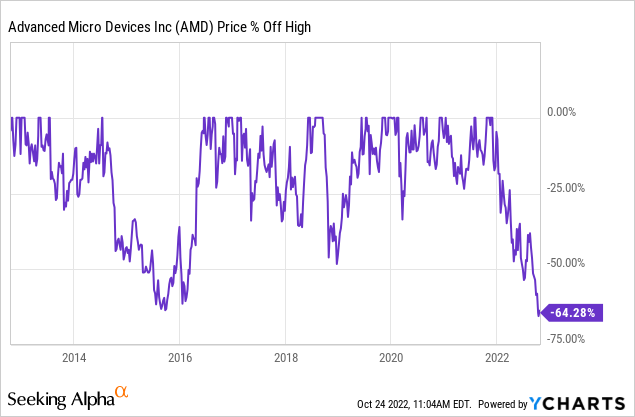

And here is a zoomed-in version of the drawdowns during the past 10 years.

We can see that AMD has historically experienced two types of drawdowns, shallow ones, as we see above that fall about -65% off the highs, and deeper ones, in which the price falls about -90% off its highs. Sure, AMD has changed over time, “it’s not the same business”, “they acquired such-and-such company and are no longer cyclical”, “their products are now better than their competitors”, and so on. All of this can be true, but what is important to point out here is that the range of prices between -65% off AMD’s highs and -90% off the highs is wide enough to include all of the changes the business has made. AMD can be a better business; they can be a different business to some degree; they can be a less cyclical business, and they can have a bright future, but they should still be expected to fall at least -65% off their highs even if those things are true, just as they did in 2015, and that is exactly what the stock is doing right now.

Anyone who bought the stock during the past two years is now underwater. Many investors, for one reason or another, thought the price was attractive during this time period. Judging from my interactions with many of them, they did not expect a decline like this to occur. Simply understanding history would have prevented that.

Now I have bought the stock, but, as we can see from the long-term drawdown history, we might not be close to the bottom, yet. So, why did I buy it now?

Investing is about probabilities, not absolutes

While I currently invest in a wide range of stocks in my marketplace service, The Cyclical Investor’s Club, as you can tell from the title, I started off specializing in deep cyclical stocks. Because these stocks are so high beta and the stock prices fluctuate so much, they offer tremendous opportunities for investors to get outsized returns. However, they are highly volatile, and they can be very dangerous if the businesses are not of sufficient quality. Lower-quality cyclicals, when they face a downturn, often lose money during the bad years because usually they have high fixed overhead costs that are difficult to adjust when demand disappears. This creates a serious risk of bankruptcy, so investors need to be extremely careful about selecting only the highest quality businesses when it comes to cyclical businesses. There isn’t much argument about AMD’s quality as a business, but I’ll share one of the best ways to determine if a deep cyclical stock or business is good enough to buy during a deep cyclical downturn.

First, I want to have historical data that shows that both the business’s earnings and the stock price have previously recovered from two recessionary downturns. This means that, first and foremost, we need two downturns worth of data to examine. It’s much easier for new businesses or businesses that have gone private and come back public, or spinoffs, etc. to make up stories about how they aren’t cyclical or how the business has changed and investors need not worry about downcycles when there is no data to examine. So, my rule is, if there is no data, then I don’t consider buying the stock. Additionally, usually, the market doesn’t have the same type of downturn twice in a row, so it’s possible for a business to do pretty well during a particular type of downturn, but then get crushed during a different type. It’s best to have two types of downturns to examine. I think it’s debatable whether the 2020 downturn can be counted as a ‘real’ downturn for many businesses (it certainly was not a normal downturn for semiconductors, because they flourished). So, ideally, we need data going all the way back to 1999. That rules out a lot of stocks, but that’s okay. I only need about 10 semiconductor stocks to buy in order to max out my 10% portfolio allocation (give or take). And right off the bat, we have AMD, MU, and NVDA for which we actually have the data. For all three of these stocks, both earnings and stock price have made new highs during the current cycle, so they have shown they can bounce back from a serious downturn.

Now that the question of quality and whether they will eventually bounce back is out of the way, as investors, there are two factors that matter to us. The first is how low we might be able to buy the stock. And the second is how long the stock will take to at least recover its old highs. My view on this price recovery is that if similar market conditions occur again in the future that occurred during the previous peak, then it is reasonable to expect that the stock price will trade at similar levels (because humans and investors don’t really change that much). Usually, I look five years into the future, but if a stock is purchased deep enough off its highs, then 10 years is a possibility. After all, if I buy a stock -90% off its highs, and it returns to its old highs, then that’s a 9x, and I’m fine waiting 10 years for that.

If we assume the stock price will eventually recover (based on history), now we are left with two sets of probabilities, how far the price falls off its high, and how long until it recovers. Historical corollaries, while useful, can’t be counted on for their precision. For this reason, we need to use a strategy that has a good probability of being ‘roughly’ correct at producing attractive returns. During times when we are not in a bear market, I consider +15% to +20% annual returns to be attractive, and if we are in a bear market then I aim to produce better relative returns than the S&P 500. So, when I buy a stock like AMD, I don’t want to buy the stock before it will produce returns around these levels. And I am typically wrong about one out of five times using this strategy, so that needs to be taken into account as well. I have to have enough big winners to make up for the occasional loser and the average performers that fall a little short of the desired goal.

This also needs to be balanced against the time that I spend holding cash, waiting for my desired prices. Often late in the economic cycle, I will end up holding cash if nothing else is attractive, so since early May, I’ve roughly held about 30% cash on average. In 2022 the cash has been an advantage, but there are times, as in the summer of 2020 when I held slightly more cash than that, when the cash was a pretty big drag on portfolio performance. I bring all this up because I need to aim for high enough returns to make up for the opportunity costs I’ve potentially suffered over time, and also make up for the losers that might occur. You don’t want to set your return goals too low if you don’t have to.

With AMD stock, it was pretty obvious to me that the odds of it falling more than -65% off its highs were extremely high. I had little doubt it would hit my initial buy price. That was a relatively easy call to make because it didn’t even take a recession for the stock to fall that far in 2015. (Same with Micron.) But now predicting how much deeper the stock price falls is much more difficult.

My second buy price was much deeper, a full -90% off AMD’s highs at about $16.45. If my first buy price had a 90% chance of hitting, then the second buy price probably has more of a 10% chance of hitting. But 10% is a long way from zero, and I believe that any investor in AMD stock must have a very clear understanding that a price this low, or near this low is certainly possible. The AMD position I just purchased, would be down close to -70% at that point.

Commenters on my last AMD article really took issue with this low buy price. Part of the issue I think came from a misunderstanding about what my “buy prices” really are. The financial industry is structured in such a way that sell-side analysts (whose description literally should tell you their job is to sell you stocks) usually puts out what they call “price targets”. I’m going to be frank here and tell you that those “price targets” are totally useless, and usually counterproductive for any investor listening to them. The average AMD analyst price target to start this year was roughly $150 per share. That should tell you all you need to know about “price targets”. Because I actually invest my own money in these stocks, what I share are not “price targets”. I share “buy prices”. These are prices I will actually buy the stock with my own money. Some of the buy prices will have a higher probability of hitting, but usually, those will produce lower returns than the buy prices that have a lower probability of occurring.

If we assume that today’s price around $57 had a 90% probability of hitting and $16.45 has a 10% chance, then you can figure that at all the prices between $57 and $17, there is a corresponding range of probabilities, and the lower the price you aim for, the lower the chance of it hitting, but the bigger the reward you will likely receive several years from now when the stock price recovers. Now, because the $16.45 price has a low chance of hitting, I don’t have cash on the sidelines earmarked for the purchase. I will almost certainly have to sell something in my portfolio to get the cash to buy it should it occur, but I will do so because AMD’s potential 9x return if purchased at that price will likely be higher than most of the stocks in my portfolio at the time. So, I don’t really have an opportunity cost associated with that low buy price because I won’t be sitting on cash waiting for it.

Because I write about stocks publicly and because I have an unconcentrated portfolio I usually only share one particular buy price for each stock (it’s too hard to track performance otherwise), but occasionally in circumstances like this, I will have a maximum of two buy prices. This approach allows me to easily track the results of the ideas that I share. However, I don’t necessarily think that is the best way for individual investors to approach the stock. I think it’s perfectly acceptable to take 2% of your portfolio and to start layering into AMD at today’s price at an even pace all the way down to the $16.45 level. That way all your money is going in at decent prices, but you don’t have to try to pick the bottom, and your mind will be focused on buying more, rather than how much you are down as the stock price potentially falls from here. Or, you could buy a 1% position here, and then slowly layer in the other 1% on the way down. If you have cash left over after the stock bottoms, you can find someplace else to invest it.

Psychological and portfolio considerations

One of the most difficult parts of investing in deeply cyclical businesses is having the ability to hold through a deep drawdown. For example, if you buy a stock when it is -30% off its highs, and it goes on to fall over -65% off its highs as AMD has done, the investment isn’t down -30%, it is down -50%. Imagine buying a stock that peaked at $100 when it fell to $70 (-30%), and it goes on to fall -65% to $35. The difference between $70 and $35 is -50%. That sort of drawdown, especially after an investor thought they were getting a great deal when the stock was down -30%, can be very difficult to deal with psychologically. And usually what investors do at that point is capitulate and sell, and if they don’t do that and they buy more, and then the stock falls another leg down, they really feel the pain. Often by that point it’s nothing but bad news about the stock and the investor assumes it could never recover its old highs and sells.

Having a second, “worst case scenario” buy price in mind that has historical precedent, can go a long way to alleviate the psychological burden of experiencing a deep drawdown. And understanding that the price can fall very deeply and still fully recover in a timely manner helps, too. I’ve had more than one deep cyclical stock fall -50% after I bought it and fully recover its old highs (Albemarle (ALB) immediately comes to mind).

My last piece of advice for investors buying AMD is to limit the initial portfolio weighting to 1% or 2% (I don’t rebalance after that, though, and I let the winners fully recover their old highs). Semiconductor stocks generally move together, but there are individual risks that might come to any individual stock. So, my preference, is to limit my initial semiconductor exposure to an approximate maximum of 10% portfolio weighting, and to spread my bets around. So far this downcycle, I’ve purchased AMD and MU, but there are several other semiconductor stocks I’m prepared to buy if they fall a little deeper. Ultimately, a 10% weighting to such volatile stocks is enough. Most of them, if purchased at the right price, will produce returns in the 100% to 200% range. All other things being equal, that would take a 10% position up to 20% of a portfolio, or higher. There is no need for bigger exposure than that.

When you have an unconcentrated portfolio, it’s the process that produces steady results over time. My portfolio, which is a mixture of stocks and cash, has been far less volatile than the S&P 500 index or even a 60/40, even though a good portion of the portfolio has high beta stocks like semiconductors. This makes it a little easier to handle the volatility because you place your trust in the process and not in an individual business or CEO.

Conclusion

Now is a good time to start buying AMD stock. However, investors need to understand the stock price has probably not bottomed, yet. My expectation is that within five years AMD stock will recover its old highs, and that will produce good returns for investors who start buying now. The most important thing for investors is to have a plan ahead of time and to understand that history is likely to repeat. Also, I suggest spreading one’s bets around the semiconductor industry rather than concentrating in one stock.

Be the first to comment