William_Potter/iStock via Getty Images

Transcript

Markets are rallying on hopes that policy tightening is nearing an end – even as the Fed is set for another large rate hike this week.

We don’t think that’s the case, as central banks haven’t fully acknowledged that hiking rates enough to tame inflation will cause recessions.

On top of this, balance sheet reductions could hit global markets.

1) Balance sheet reductions bad for bonds

The Fed started trimming its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet this summer, and the Bank of England started doing so this week.

That would put upward pressure on bond yields.

2) Federal Reserve (Fed) policy outlook

The Atlanta Fed research suggests a $2.2 trillion drop in its balance sheet over three years would have the same effect as a roughly 30-basis points hike in a normal, non-crisis scenario.

3) European Central Bank (ECB) policy outlook

For the ECB, reductions manifest as letting bonds runoff and incentivizing banks to hand back emergency cash they borrowed and no longer need.

A shift from this next year could widen the differences between the yields for member countries’ bonds. That’s particularly a concern for Italy.

We see central banks on a path to overtighten policy, and their balance sheet reductions would put more upward pressure on bond yields.

We’re underweight government bonds and stocks.

___________

Markets are rallying on hopes policy tightening is nearing an end – prematurely, in our view. We think the Fed, like other developed market (DM) central banks, will only stop when the severe damage from rate hikes is clearer. Rates have already hit levels that may trigger recessions, in our view. Plus, shrinking central bank balance sheets put selling pressure on long-term government bonds and risk causing market mayhem. That keeps us underweight stocks and government bonds.

Balance sheets to shrink

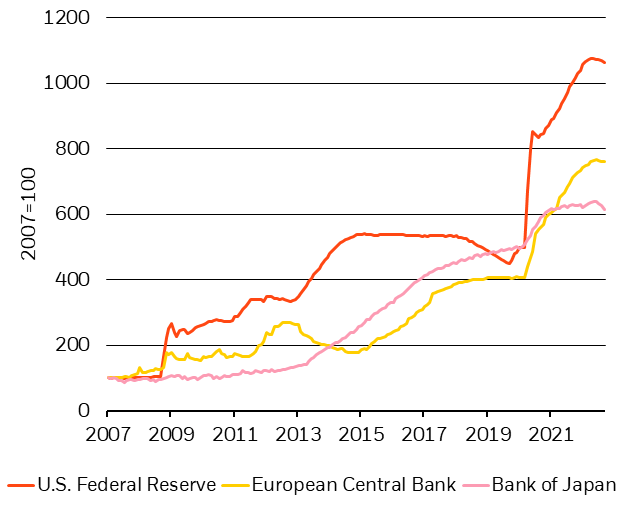

Central Bank Balance Sheets, 2007-2022 (BlackRock Investment Institute and Refinitiv Datastream, October 2022)

Notes: The chart shows central bank total assets rebased to 100 at the start of 2007 for the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and Bank of Japan as a measure of how much quantitative easing or tightening central banks have been conducting.

Rate hikes have consumed the market’s attention this year. And rightly so. Central banks are taking a “whatever it takes” approach to pushing inflation back down to their targets, in our view. Just last week, the European Central Bank (ECB) raised rates another 0.75%. Markets expect the Fed to do the same this week. That’s a record pace for the ECB – one it’s signaled may slow – and the fastest hiking cycle for the Fed since the 1980s. Most major central banks aren’t fully acknowledging that hiking enough to tame inflation will cause recessions, as we see it. There’s another specter looming over markets: balance sheet reductions, or quantitative tightening (QT). Balance sheets have already started to dip this year. (See chart above.) Central banks selling or ceasing to buy government bonds could increase the risk of financial dislocations from yield spikes sparking risk asset selloffs.

Bond yields have already jumped markedly this year. U.S., euro area and UK 10-year bond yields have each surged nearly 250 basis points since the start of the year. That’s primarily because markets are expecting higher policy rates. And investors aren’t yet demanding significantly higher compensation, or term premium, for the risk of holding long-term bonds, as we’ve said before. QT could push up term premium, boosting the structural increase we see ahead as markets price in inflation risk and rate volatility in this new regime.

Varied QT playbooks

The process, timing and effects of QT will play out differently across central banks. The Fed trims its balance sheet by letting bonds run off, or reach their maturity date without replacing them, rather than selling them. That process started in June. It’s unclear how long it will continue for, but the trimming of the $9 trillion balance sheet increases the risk of overtightening policy as the Fed keeps up aggressive rate hikes. A $2.2 trillion drop in the balance sheet over three years would hit bond markets the same as a roughly 30-basis point hike in a normal scenario – and an 80-basis point hike in times of crisis, Atlanta Fed research shows. The U.S. Treasury is looking at potential disruptions to trading liquidity, asking primary bond dealers if it should buy back some less-traded bonds to reduce volatility as liquidity, or the ability to trade, has deteriorated.

Kicking off its QT, the ECB said that in November it would start incentivizing banks to hand back the emergency cash they borrowed and no longer need. Bond runoffs may be in store for next year. QT could widen the differences between the yields for member countries’ bonds. That’s particularly a concern for Italy given its current account deficit and heavy debt load. The ECB’s anti-fragmentation tool and continued reinvestment of maturing bonds during its pandemic program may stave off some widening of peripheral yield spreads. This week, the Bank of England (BoE) will become the first major central bank to sell bonds as part of QT, temporarily delayed during the turmoil of the long-term gilt selloff that prompted renewed purchases. The UK episode shows how financial dislocations can cause a delay or pause in QT programs. That may feed perceptions of financial dominance – that central banks have no choice but to keep buying bonds due to market strains.

Our bottom line

We think further, if slower, rate hikes are coming along with QT. QT may add to market strains and reasons why investors start demanding term premium, driving long-term bond yields higher, so we stay underweight DM bonds. Within an underweight to Treasuries, we prefer short-dated bonds given better returns and less duration risk. We stay underweight DM stocks whose valuations don’t reflect the recession we expect to hit corporate earnings.

Market backdrop

Developed market stocks rebounded and bond yields last week fell on hopes that major central banks will start to slow and halt rate hikes. We don’t see this as a catalyst to turn positive on risk assets. Rates will – and may already have – reached levels that constitute overtightening, making recessions foretold, in our view. The U.S. PCE data may embolden the Fed and is consistent with it pushing ahead with hikes causing major economic damage if it wants to bring inflation down to target.

All eyes are on the Fed as it is set for a fourth straight 75-basis point hike. Markets are hoping it will slow and eventually stop hiking. But we think the Fed will only stop raising rates once the economic damage from their tightening becomes clear. U.S. payrolls will be closely watched for any signs of whether slowing activity is impacting demand for labor.

Be the first to comment