“DOUBLE COUPONS” ON CORPORATE LOANS AND BONDS!

mphillips007

Credit Investing: Corporate Loans & Bonds On Sale

Lots of investors don’t know much about “credit investing,” which is where you essentially bet on a company’s ability to stay in business and pay off its debts.

I’m not talking about typical “bond investing” which usually refers to buying the long-term, fixed-rate bonds of highly-rated corporations or even government-issued Treasury bonds. Those bonds involve virtually NO credit risk, and as a result, you get paid very little for holding them. The risk you are taking, essentially, is interest rate risk; the risk that you’ll be stuck with a long term bond for 10, 20 years or more at some puny interest rate of 2, 3 or 4%, even if rates go up much higher because of inflation or Fed policy, etc.

Lately, with inflation having risen and the Fed raising interest rate targets, we have seen these bond rates rise by a couple points, so investment grade and treasury bonds are at higher levels than they’ve been at in years, with the 10-year treasury over 4%.

But that is still far too low to be of interest to Income Factory® investors whose goal is to earn what has been the average equity rate of return (9-10% or so) for the past century. A total return of 9-10% over the course of one’s investing career would be quite attractive, doubling and redoubling one’s portfolio value every 7 or 8 years. In fact, achieving an “average” equity return would actually exceed the return of most investors, especially those who try to “beat” the averages and end up doing worse than average because of their attempts to time the market or to avoid short-term volatility by “hedging” their portfolios with lower-yielding but supposedly more “stable” assets (like long-term bonds) that merely lock in sub-standard returns or capital losses. That’s like “stabilizing” a canoe by tying a big rock to it; it may be less tippy but it also moves a lot more slowly.

“Credit investing” means taking real corporate credit risk, but getting paid higher yields that actually compensate you for the risk that you’re taking. At times like this, with an expected economic downturn or recession ahead of us, a “fear factor” grips the credit markets and results in what has been called the “worry discount” in high yield corporate loan and bond market. The result is what many credit market experts regard as excessive price discounts and “over-compensation” for the actual credit risks current investors are taking.

Let’s Look At The Math

The typical way to invest in high-yield corporate credit is to buy (1) senior corporate loans, also called “leveraged loans” (which are secured, floating rate loans to non-investment grade companies ; i.e. rated BB+ and lower) and/or (2) high-yield corporate bonds (unsecured, fixed-rate debt, issued by the same cohort of non-investment grade companies).

I invest in the loans via closed-end funds (“senior loan funds”), as well as by buying the equity of Business Development Companies (“BDCs”), which are financial companies that specialize in making senior secured, floating rate loans to middle-market companies. Both the funds and the BDC equity have been paying distributions in the 9-10% and even higher range lately, largely because markets are skittish right now about the risk of economic downturn and/or recession, which would drive up default rates and credit losses for credit investors. (It obviously won’t do much for equities either.)

If we look closely at the math, it becomes obvious that credit markets have become overly skittish (which is not unusual), to the point where current prices and yields present investors with what appears to be an unusual opportunity.

We’ll start with loans, and then do a similar analysis for high yield bonds. The most recent Eaton Vance Floating Rate Loan Monitor shows the $1.4 trillion (par value) senior loan market selling at a market price of 91.9 cents on the dollar. This discount of 8% is supported by the monthly portfolio report of Eagle Point Credit (ECC), which shows that the 1864 individual underlying corporate obligors included in all of its CLO investments have an average market price on their loans of 91.4% of par, very close to the Eaton Vance reported figure. Meanwhile, both Eaton Vance and ECC report the average spread (i.e. margin above the base rate) on their reported loans is about 3.6%, which when added to 3.03%, the current Secured Overnight Financing Rate (“SOFR”) that recently replaced LIBOR as the base rate, brings the average loan coupon rate to: 3.6% + 3.03% = 6.63%.

That’s the rate an investor would get who bought the loan at 100% of its face value, or par. But with a discount of 8%, it means an investor is actually collecting that 6.63% coupon on a loan they only have to pay 92 cents on the dollar to buy. So the cash yield is actually: 6.63/92 = 7.2%.

That’s nice, but not all. Remember we bought the loan for 92 cents on the dollar, but at maturity the borrower will pay us back 100 cents. That’s a capital gain on our purchase price of: 8/92 = 8.7%. Assume the loan has another 4.5 years to run, so we’ll amortize that 8.7% capital gain over those 4.5 years: 8.7%/4.5 = 1.9% per year.

Adding that together we see that a loan whose originally negotiated coupon (reflecting the risk perceived in the market when the deal was first done) was 6.63%, can now be bought on the market for a discounted price that raises its overall yield to 7.2% + 1.9% = 9.1%.

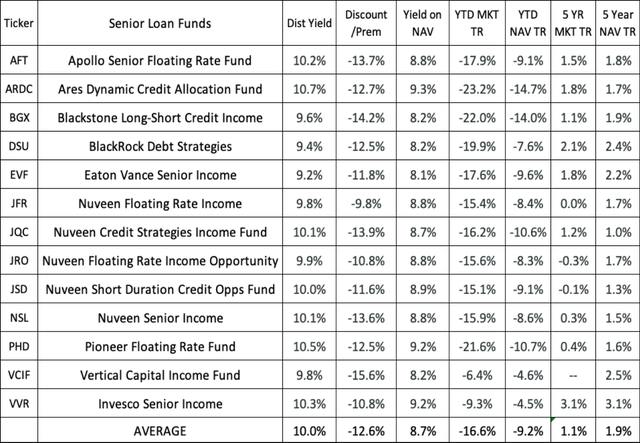

If we look at a representative selection of senior loan funds from CEF Connect, we can see the distribution yields averaging out to 10%, much higher than what senior loans and senior loan funds were yielding a year or so ago. The discounts on the funds, averaging 12.6%, provide an additional margin of safety. Those are discounts on the fund’s net asset value, which reflects the mark-to-market value of the loans held by the fund. But we saw earlier that the market price of the loans is only 92% of their par value (i.e. the amount investors will collect when the loans mature.) The 92% of face value is the market’s way of saying that it believes the value of the loans will shrink by 8% between now and when they mature. But the average secured loan recovers at least 60% of its principal if and when it defaults. That means the average defaulting loan loses, after the recovery is collected, about 40% (or usually less). So with 40% losses, you’d have to have 20% of your loans default in order to lose 8% of your portfolio in credit losses: 20% defaults X 40% loss on defaulted loans = 8% overall portfolio loss.

In the “Great Recession” of 2008/2009, we reached 11% defaults, which was considered astronomical at the time. Economists and rating agencies are predicting maybe as high as 4 or 5% if we have a bad recession this time around. So the market is building in a margin about 4 or 5 times what most economists are projecting actual default rates will be, and almost twice what they actually were in the Great Recession.

SB/CEF Connect

Meanwhile for us as closed end fund investors, the margin of safety gets even better. That 8% haircut is what the market is charging investors, like our closed end funds, to buy healthy performing loans. But we can buy those funds for an additional 12% discount on their net asset values, which are computed based on the market value of their loan holdings.

So the fund buys loans at 92% of their par value, which is reflected in the funds’ NAVs; and then we buy the funds at 88% of their net asset value. That means we’re paying: 88% X 92% = 81% of the ultimate par value of the loans in the portfolio. That’s a 19% discount on the loans, providing substantial additional margin above what the loan market itself has already built in.

High-Yield Bond Funds: Similar Opportunity

Similar math in the high-yield bond market. The S&P Global High Yield Corporate Bond Index shows the average high yield bond currently selling at just under 83 cents on the dollar, for a discount of 17%. It pays an average coupon on its face value (100 cents on the dollar) of 5.69%. That translates into a yield on its discounted purchase price of 6.85%.

But as we saw with investing in discounted loans, that’s not all. The investor who buys the loan for 83 cents on the dollar gets to collect 100 cents on the dollar from the issuer at maturity, a capital gain of 17 cents on the original investment at 83 cents, spread over 6.45 years on average. That’s a total gain of 17/83 = 20.4%, or an additional gain of 3.2% per year, which if added to the 6.85% per annum coupon brings the overall yield to 10%.

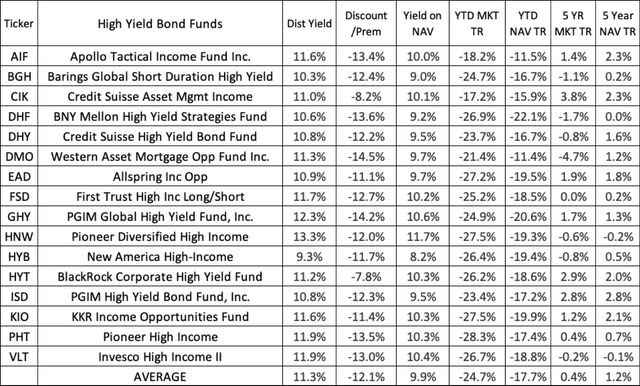

Here is a representative sampling of closed-end high yield bonds funds. I have selected those mostly falling into the 9-12% distribution yield range, although if you sort on the CEF Connect or CEF Data sites you will find other more aggressive funds with higher yields. But 9-12% is plenty of yield for me and most investors seeking an “equity return” level.

The point here is that, like the senior loans, we have closed-end funds whose net asset value is based on the market value of their assets. That means, with an average discount of 17%, the funds are marking their bonds to market at 83 cents to the dollar, in calculating their own NAVs. A 17% discount, of course, means the market is building in an assumption of a 17% average loss on each bond. Since defaulted high yield bonds, on average, recover at least 40% of principal (i.e. lose 60%) that means in order to lose 17% overall you’d have to have 28% of your bond portfolio default. (28% defaults X 60% loss on each default = 17% overall loss.) As mentioned earlier, only 11% of high yield companies defaulted in the Great Recession of 2008/2009, so to have 28% default would be over two and a half times as many.

SB/CEF Connect

Besides the 17% discount that is already priced into the carrying cost of its assets (i.e. the high yield bonds), as retail investors we get to buy those funds at discounts; currently averaging 12% for the funds listed. Putting the two discounts together: Fund NAVs calculated at 83% of their bonds’ actual par value; and we buy the funds at 88% of that NAV value; so we are getting the underlying bonds at 88% X 83% of their underlying par values. (88% X 83% = 73%; or an overall discount on the underlying bonds of 100% – 73% = 27%.)

So the high-yield bond market is overcompensating investors even more than the secured loan market, on a relative basis. That’s OK, since high yield bonds, being unsecured and further down the capital structure, are riskier than senior secured loans. Either one seems like a good deal.

Bottom Line

An opportunity to collect 10-11% in cash, with assets that are relatively predictable cash-generating machines, with considerable discounted “value cushion” beneath them.

One more thing: Every time we talk about “high yield” loans and bonds, we invariably get comments from readers who go on and on about the risks and dangers of high yield or “junk” credits. Most of these same investors hold mid-cap and small-cap equities, either directly or through mid-cap and small-cap funds. They don’t seem to realize that mid-caps and small-caps are virtually all non-investment grade credits, in other words the same companies that issue leveraged loans and high-yield bonds of the sort we are discussing here. The difference is that the loans and bonds are a lot safer and more secure than the equity below them on the balance sheet. So before anyone starts getting all excited about how “risky” and “dangerous” these credit investments are, I suggest they check their own equity portfolios first.

Be the first to comment