Lemon_tm/iStock via Getty Images

What’s up with growth stocks? For nine years, investors couldn’t get enough of them. For the past fifteen months, investors don’t want to touch them. Was it a simple matter of rising interest rates? If so, could a recession accompanied by falling rates help them regain leadership over value stocks? Or does growth as a category have a deeper problem? This article takes a shot at the answers to these questions.

Growth Achieved Leadership And Then Came Apart

Growth stocks led the market for almost a decade starting in 2012, and they led for good reasons. For a few years after the blow-up of the dot.com bubble, growth flew under the radar, despite the fact that new market leaders were beginning to emerge. The period starting as far back as 2005 was a golden age for creating disruptive business models. Many involved new technology. The boom started because a few companies had hit upon a great idea and were going gangbusters. Toward the end, like all speculative booms, it got out of hand.

As of May 31, 2022, the top ten stocks in the S&P 500 Index ETF (VOO), were in descending order Apple (AAPL), Microsoft (MSFT), Alphabet (GOOG), Amazon (AMZN), Tesla (TSLA), Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A)(BRK.B), Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), UnitedHealth (UNH), NVIDIA (NVDA), and Meta (META). Seven of the top ten were large cap Growth stocks. The highest ranked value stock was Berkshire Hathaway at #6. That tells you the extent to which growth stocks had taken over the index. That May 31 list taken from Vanguard includes the recent fall of NVIDIA and Meta, which had ranked ahead of Berkshire two months earlier.

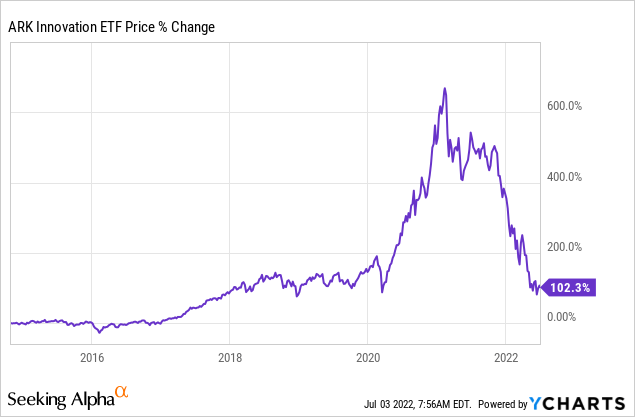

Coming in the wake of the established stalwarts of growth were a group of less established smaller growth companies which attempted to replicate the success of their established peers. They had less substantive business models, but nevertheless managed to grow revenues and market caps. What they didn’t have was much in the way of positive cash flow. Many burned through cash at a rapid rate. ARK Innovation ETF (ARKK) provides a snapshot of these stocks. Here’s a chart of the rise and fall of speculative growth stocks as represented by ARKK:

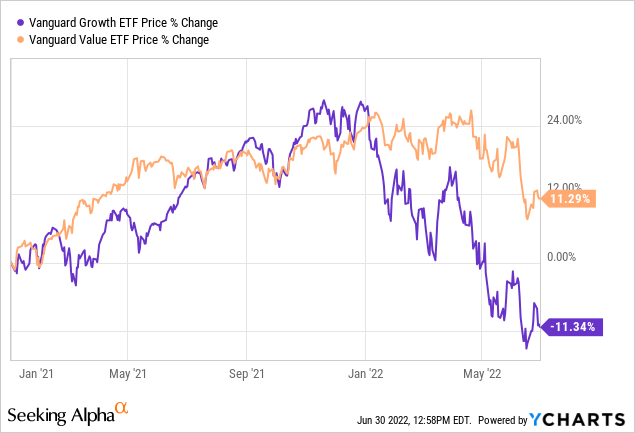

When the highflyers broke, they broke as bubbles always do, and they were accompanied by a number of similarly speculative vehicles such as NFTs and Bitcoin, neither of which had any discernible value aside from the hope that a greater fool would come along and pay you more for them. Most of the more established growth companies held up better, but they too finally broke in November 2021, and their decline accelerated in the first six months of 2022. This comparison of the Vanguard Growth ETF (VUG) and the Vanguard Value ETF (VTV) clearly identifies the moment when Growth leadership ended and Value took the lead:

You can see at the tail end of the chart that Growth seemed to be coming back a little in relative terms starting in mid-June before falling hard again in the past few days. You can easily track short-term relative strength of Growth and Value intraday by checking the percentage up or down of VUG and VTV. Even for a single day, the difference can be striking. At times, it’s like an hour by hour tug of war.

What Are Growth Stocks Anyway?

Growth Stocks are stocks that grow. That’s the short version, and it states the obvious, but it’s a little more complicated than that when it comes to putting together an index. How fast does a company have to grow to be a growth stock? What metrics are important? What metrics can be disregarded? How do the various indexes, funds, and ETFs decide which companies belong in a Growth Index? That’s the question I started with in a recent article comparing VOO (which includes the entire S&P 500) with VUG.

The Vanguard Growth ETF is an ideal vehicle for owning large cap growth. VUG contains 269 holdings, of which the top ten make up 49.16% of the total market cap. It has the usual low Vanguard expense ratio at .04%. Whether or not the present is an ideal moment for buying growth stocks, diversified large cap growth of the kind contained in VUG benefits from the fact that growth in the 20%-30% range quickly reduces high valuations. If growth is still overvalued, many of its leaders will work off that overvaluation within two or three years. For that reason, many investors want to own at least some established growth stocks regardless of their current market opinions.

Tech amounts to 41.72% of VUG, while adding Consumer Cyclicals and Communication brings the total to more than 70%. The top ten holdings present a portrait of American business success. Here’s the list including percentage of the index: Apple (12.81%), Microsoft (11.31%), Amazon (5.77%), Alphabet Class A (3.80%), Tesla Inc (3.48%), Alphabet Class C (3.40%), Meta Platforms (2.48%), NVIDIA (2.46%), Visa (1.89%), The Home Depot (1.75%). It’s easy to see at a glance that the top growth stocks represent a list of the big winners over mainly the past two decades. With VUG, you own all of them along with 259 other and somewhat smaller growth stocks. But exactly how does Vanguard’s VUG define “growth”?

The Growth ETF is actually put together with an entirely different methodology than its Value equivalent. Vanguard undertakes to define both “growth” and “value” in a rigorous way using the CRSP Indexes (Center For Research In Security Prices) developed by the University of Chicago Booth School Of Business. Its premise is that Growth is primarily about the future. Here’s the list of factors used in the CRSP methodology for defining “growth”:

Growth Factors Used In Multi-Factor Model

- Future Long-term Growth in Earnings Per Share

- Future Short-term Growth in Earnings Per Share

- Three-year Historical Growth in Earnings

- Three-year Historical Growth in Sales

- Current Investment-to-Assets Ratio

- Return on Assets

The estimates for both long and short term growth are sourced from I/B/E/S (Institutional Brokers’ Estimate System) which derives data from over 18,000 analysts. The final four criteria for Growth are simple and easy to reduce to a known number. Together, the six factors produce a composite number by which all stocks can be compared. What stands out in the Growth list is the fact that the majority of factors are about the future factors 1 and 2 explicitly and factors 5 and 6 which involve present metrics which forecast the future. Factors 1 and 2 can only be estimated.

Of particular note is that the CRSP methodology has nothing to say on the subject of price. It follows that there is nothing to be said about valuation. In the Value model, only Factor 2 involves a future projection while price is involved in three of the five criteria:

Value Factors Used In Multi-Factors Model

- Book to Price

- Future Earnings to Price (3 years)

- Historical Earnings to Price (3 years)

- Dividends to Price

- Sales to Price

What stands out in comparing the two is that Value is firmly tethered to the ground by valuation. It contains a single future projection for earnings of just three years. Growth is all about the future, including both the short and long-term future and the metrics of investment and return on assets. Taken together, the ratio of investment to assets and the return on investment are the best predictors of that future. For growth, there is nothing having to do with price or valuation.

On the one hand, this is a reasonable exclusion for promising growth companies in their infancy including Amazon (AMZN), which focused on investment rather than immediate earnings, and Meta (then Facebook) (META), which focused on growth in customers and clicks before undertaking to monetize. On the other hand, the absence of any measure of valuation suggests that for growth stocks, especially in their early days, there are no limits to valuation. Whatever you pay for future growth is fine. It will work out over time. This way of defining growth leaves a great deal in fallible human hands and is one reason that growth cycles tend at some point to get out of hand. There just isn’t anything to impose a limit on price.

What Triggered The Huge Drop In Growth Stocks?

There are several answers. It was easy for the newer and more speculative stocks to get out of whack. The presumption was that they owned the future, and the future would take care of the high price. You could always make some kind of case for revenue growth and investment as a percentage of assets, and tell yourself that everything else will come at some future point. Bitcoin was perfect because it produced no return and its advocates could promise freely that its value would become manifest at some vanishing point in the future. It reminds me of Schopenhauer’s observation that we wouldn’t mind death so much if assured that we would wake up and be fine in a thousand years. Who wouldn’t wish to write insurance on that bet? I can’t avoid a wry smile when a talking head on CNBC says Bitcoin is underpriced at such and such number. I always want to ask, underpriced as against what? When does it start to throw off cash? The crash of essentially valueless “investments” like these finally came as if someone had pointed out the emperor’s new clothes.

It’s perfectly good to push future returns out to a vanishing point as long as interest rates are close to zero. Silly prices weren’t limited to speculative growth stocks. Even the large cap growth leaders had come to trade on a basis of distant future returns. So did a few younger stocks which seemed to have real business models. I wrote this article, “A Berkshire Hathaway Value Investor Looks at Snowflake, Shopify, and Palantir,” published on July 25, 2021. I settled on Snowflake (SNOW) as the one with the most promising business model and best prospects for long future growth. I bought a pilot position myself, but included guidelines for progress that SNOW needed to hit for me to add or hold. One was that it needed to continue with 100% annual revenue growth while adding a much smaller number of shares outstanding. At the next earnings report it failed on both counts and I sold instantly. It turned out to be a good sell.

In November 2021, even the best companies in the growth sector finally gave way. By then, inflation was becoming a huge problem and higher interest rates were inevitable. The value of future cash flows (or dividends or earnings) is a series discounting future returns by a denominator starting at (1+R) and extending to (1+R) to the N power, R being the number used to discount and N being the number of years. When N is close to zero, the returns of a growth company in the distant future are almost as valuable as present earnings.

Although we might take issue with this in practical terms, the mathematics of it are clear. When rates generally rise, the value of a company whose returns are assumed to be far out into the future are greatly reduced. Value stocks, which have present earnings, dividends, and cash flow, suffer less relative price damage. What rate increases do is take away the blissful future on which growth stock prices are based. The ability to push everything into the future more or less enables growth investors to argue that no price for growth is too high. That’s the simple math. The distant future will take care of everything.

The argument, then, is that low rates over a decade led to extreme overvaluation of growth stocks and rising interest rates popped the bubble. If that were the end of it, you might expect growth stocks to recover powerfully if rates turned down in a decisive way, and there is some evidence that rates are indeed turning down. There’s a growing expectation that the Federal Reserve will be compelled to shift from fighting inflation to fighting a recession.

But wouldn’t the recession itself be bad for Growth? Probably not. It could be bad for Value, which contains a number of cyclical areas which will suffer from a slower economy, but Growth tends to get a pass when it comes to economic weakness. Most of the current established growth stocks provide products and services which are not vulnerable to economic weakness. Value stocks need a growing economy to do well, while growth stocks create their own growth.

So will Growth retake the lead if a slowing economy leads to lower rates? Can Growth return to its previous lofty valuations? Not so fast. There’s one other question hanging over the growth companies, which have been the major market leaders for a decade.

Companies Have Life Cycles Just Like People; Can They Age Gracefully?

Over the past few weeks, my wife and I watched the series of James Bond films with Sean Connery in chronological sequence. Watching the fifth Connery film was a painful experience. Connery had been called out of retirement by the irresistible offer of $1.25 million, which was real money in those days. He was woefully out of shape, and it showed in the way his elegant suit pinched his midsection when buttoned. That’s a phenomenon I am all too aware of. His hairline had receded, and his hairpiece was more obvious, while the fight scenes and witty quips felt less authentic. The film was Diamonds Are Forever, and I realized that it was the youthful, witty, and invincible Sean Connery that I hoped would be forever.

Alas, it happens to all of us, including companies. The best we can do is accept and play the role of older heroes. Connery eventually learned and played comic heroes who proved to be surprisingly tough despite being bald and not especially fit. The best we can do, as people or companies, is be terrific for our age and stage of life. We all eventually devolve into value stocks. It’s the natural course of things. It’s not a bad thing at all once we accept it. The world puts a lower price on us, turning us into supporting actors like the older Connery brilliantly portraying Harrison Ford’s father in Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade. May we all age so well.

Many growth leaders of the past decade are beginning to look a little long in the tooth. Here’s a short review of the growth stocks listed above:

- Apple is hanging in there, but with modest top line growth. It is increasingly defined by value characteristics. It has good earnings growth, thanks to share reduction through buybacks, as well as a rising dividend. Those are markers of an excellent future Value stock.

- Microsoft has better top line growth and earnings growth, a modest boost from buybacks, and a rapidly rising dividend. It’s more pricey than Apple. It still looks like a growth stock entering middle age.

- Alphabet still grows at a good clip and has both revenue and earnings growth, just started buybacks, and pays no dividend. It sells at a Value price. Is it dirt cheap, or is it at risk from its many enemies? Cheap, I think.

- Amazon definitely sees itself as a growth stock, grows at a growth stock rate, and trades at a growth stock multiple. With problems mounting in its primary business, it needs for AWS to keep coming through.

- Tesla has the growth numbers, but what about its competition? Will it eventually sell most of the cars sold on the planet?

- NVIDIA has growth numbers at a moderate price and a minuscule dividend. It’s part of a growth industry. It got cheaper in the first half of 2022.

- Meta has wonderful growth numbers, but is beset by enemies and is priced as if it’s going out of business. Is it? Analysts have binary views on it. Some are going to be very wrong and others are going to be very right. I’m a bystander.

- Netflix (NFLX) was once on the top ten list and is no more. It’s the model of the broken growth stock which underpriced its product and never broke through to positive free cash flow. Uber (UBER) is younger but looks very similar. Netflix may never make it to the stage of being a value stock, and Uber is at risk of doing the same.

The Tough Middle Age Of Growth Stocks, And The Dearth Of Current Contenders

What makes it tough to transition from growth to value is contained in the two very different sets of CRSP factors above. A value stock is not just a growth stock selling at a moderate price. A growth stock is not just an ordinary stock with above average growth. It would be more accurate to say that a growth stock is about outstanding growth, with little reference to price. A value stock is about the present, recent past, and near future. Valuation begins to matter as growth begins to slow.

Of the stocks discussed in the above section, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and NVIDIA clearly continue to be growth stocks. Apple is in transition from Growth to Value, meaning that the five-factors defining Value will soon fit better than the six-factors defining Growth. Oddly enough, most factors of value stock UnitedHealth match closely the same factors for Apple, including a moderate P/E ratio. Apple and UnitedHealth both have far better numbers than Coca-Cola (KO) and McDonald’s (MCD), which have essentially no growth. Why KO and MCD have higher P/E ratios is beyond me.

Netflix is a no-category company, telling the world a fairy tale and likely headed for a buyout at a lower price. Uber? Who knows? Meta is a stock with great numbers but potentially a terrible future. In short, it’s not easy being an aging growth stock. In today’s market, it hasn’t been easy being a young growth stock either. In recent years, it was easy to stage an IPO or simply begin trading, but the outcome recently has almost always been bad. It’s hard to find listed start-ups that have great future promise. It may just be a matter of the times and cycles. There were periods like that in the past. In the 1930s and 1940s there were many innovations, but they didn’t become fully realized until the 1950s. Again, in the 2000 aughts, great companies were being born, including those mentioned above, but it didn’t become clear that they were in fact great until the 2010s.

The three new companies of the 2010s which I mentioned in the article linked above – Palantir (PLTR), Shopify (SHOP) and Snowflake – were the best I could find at the time when I wrote the article. Here’s how I see them now:

- Palantir has been crushed, but you can’t call it cheap. It still prints more shares than it earns in cash. It’s running out of time to have something to say other than “We’re doing great stuff for God, country, and shareholders, but hush, hush we can’t tell you about it.” (That would be my current Palantir article in three sentences.)

- Shopify continues to disappoint despite doing well in a few areas. I’m dropping it from my list because its otherwise pointless stock split turned out to be a power grab by the CEO. Write me a note if anything changes.

- Snowflake seems fairly close to being an authentic growth company, but it failed to meet my criteria in the first earnings report after I bought it and I sold instantly. I continue to glance at it occasionally.

That’s a pretty slim and sorry group to be the companies which will one day take the places of Apple and Microsoft in the Growth index. If you can think of others, I’ll be happy to listen. As for the more familiar speculative growth stocks, my expectation is that quite a few of them are going to zero. David Trainer has called attention to a few prime candidates on this site.

So Is It Still Value For A While?

I think so, although stocks like Alphabet and maybe Meta have room to rally. Microsoft, a little pricey, should hold its own. Amazon could be spectacular in the more distant future with the help of AWS.

There’s another informal category called GARP – Growth At A Reasonable Price. Pretty much everything I own is in that category, and I also classify myself as a GARP investor. It is made up of stocks generally in the value category but having growth that matches up with certified growth stocks. In this article, the example would be UnitedHealth. I don’t own it, but after taking a look at it here, I may buy it. GARP stocks and UNH may be my next article.

Be the first to comment