JJ Gouin/iStock via Getty Images

Money is a surprisingly complex subject.

People spend their lives seeking money, and in some ways it seems so straightforward, and yet what humanity has defined as money has changed significantly over the centuries.

How could something so simple and so universal, take so many different forms?

Flaticon It’s an important question to ponder because we basically have four things we can do with our resources: consume, save, invest, or share.

Consume: When we consume, we meet our immediate needs and desires, including shelter, food, and entertainment.

Save: When we save, we store our resources in something that is safe, liquid, and portable, a.k.a. money. This serves as a low-risk battery of future resource consumption across time and space.

Invest: When we invest, we commit resources to a project that has a decent likelihood of multiplying our resources but also comes with a risk of losing them, by trying to provide some new value to ourselves or others. This serves as a higher-risk, less-liquid, and less-portable amplifier of future resource consumption potential compared to money. There are personal investments, like our own business or education, and there are external financial investments in companies or projects led by other people.

Share: When we share, or in other words give to charity and those in our community, we give some portion of our excess resources to those that we deem to be needing and deserving. In many ways, this can be considered a form of investment in the ongoing success and stability of our larger community, which is probably why we are wired to want to do it.

The majority of people in the world don’t invest in financial assets; they are still on the consumption stage (basic necessities and daily entertainment) or the saving stage (money and home equity), either due to income constraints, consumption excesses, or because they live in part of the world that doesn’t have well-developed capital markets. Many of them do, however, invest in expanding a self-owned business or in educating themselves and their children, meaning they invest in their personal lives, and they might share in their community as well, through religious institutions or secular initiatives.

Among the minority that do invest in financial assets, they are generally accustomed to the idea that investments change rapidly over time, and so they have to put a lot of thought into how they invest. They either figure out a strategy themselves and manage that, or they outsource that task to a specialist to do it for them to focus more on the skills that they earn the resources with in the first place.

However, depending on where they live in the world, people are not very accustomed to keeping track of the quality of money itself, or deciding which type of money to hold.

In developed countries in particular, people often just hold the currency of that country. In developing countries that tend to have a more recent and extreme history of currency devaluation, people often put more thought into what type of money they hold. They might try to minimize how much cash they hold and keep it in hard assets, or they might hold foreign currency, for example.

This article is the second in a three-part series that looks at the history of money, and examines this rather unusual period in time where we seem to be going through a gradual global transformation of what we define as money, comparable to the turning points of 1971-present (Petrodollar System), 1944-1971 (Bretton Woods System), the 1700s-1944 (Gold Standard System), and various commodity-money transition periods (pre-1700s). This type of occasion happens relatively rarely in history for any given society but has massive implications when it happens, so it’s worth being aware of.

If we condense those stages to the basics, the world has gone through three phases: commodity money, gold standard (the final form of commodity money), and fiat currency.

A fourth phase, digital money, is on the horizon. This includes private digital assets (e.g. bitcoin and stablecoins) and public digital currencies (e.g. central bank digital currencies) that can change how we do banking, and what economic tools policymakers have in terms of fiscal and monetary policy. These assets can be thought of as digital versions of gold, commodities, or fiat currency, but they also have their own unique aspects.

This article series walks through the history of monetary transitions from the lenses of a few different schools of thought (often at odds with each other), and then examines the current and near-term situation as it pertains to money and how we might go about investing in it.

- Chapter 1: Commodity Money

- Chapter 2: Fiat Currency

- Chapter 3: Digital Assets

Some people whose work I’ve drawn from for this article series, from the past and present, include Carl Menger, Warren Mosler, Friedrich Hayek, Satoshi Nakamoto, Adam Back, Saifdean Ammous, Vijay Boyapati, Stephanie Kelton, Ibn Battuta, Emil Sandstedt, Robert Breedlove, Ray Dalio, Alex Gladstein, Elizabeth Stark, Barry Eichengreen, Ross Stevens, Luke Gromen, Anita Posch, Jeff Booth, and Thomas Gresham.

Fiat Currency

Historically, a number of cultures have attempted periods of paper currency, issued by the government and backed by nothing.

Often it was the result of currency that was once backed (a gold standard or silver standard), but the government created too much of the paper due to war or other issues, and had to default on the metal backing by eliminating its ability to be converted back into the metal upon request. In that sense, currency devaluation becomes a form of tax and/or wealth confiscation. The public holds their savings in the paper currency, and then the rug is pulled out from under them.

The general argument for why fiat currencies exist, is that most governments, if possible, do not want to be constrained by gold or other scarce monies, and instead want to have more flexibility with their spending.

The earliest identified use of paper currency was in China over a thousand years ago, which makes sense considering that paper was invented in that region. They eventually shifted towards government monopoly on paper currency, and combined with an elimination of its ability to be converted back into silver, resulted in the first fiat currency, along with the inflation that comes with that. It didn’t last very long.

Fiat currency is interesting, because unlike the history of commodity money, it’s a step down in terms of scarcity. Gold beat out all of the other commodity monies over centuries of globalization and technological development, and then gold itself was defeated by… pieces of paper?

This is generally attributed to technology and government power. As clans became kingdoms, and as kingdoms became nation states, along with the creation of banking systems and improvements in communication systems, governments could become a larger part of everyday life. Once gold became sufficiently centralized in the vaults of banks and central banks, and paper claims were issued against it, the only remaining step was to end the redeemability of that paper and enforce its continued usage through legal obligation.

Debasing Currency and Empowering Wars

Currency debasement often happened gradually under metallic and bimetallic currency regimes, with history of it going back three or four thousand years. It took the form of reducing the amount of the valuable metal (such as gold or silver) and either adding base metal or putting decorative holes through the center of it to reduce the weight.

In other words, a ruler often found himself faced with budget deficits, and having to make the difficult choice between cutting spending or raising taxes. Finding both to be politically challenging, he would sometimes resort to keeping taxes the same, diluting the content of gold or silver in the coins, and spending more coins with less precious metal in each coin, while expecting it to still be treated with the same purchasing power per coin.

For example, a king can collect a 1,000 gold coins in taxes, melt them down and make new coins that are each 90% gold (with the other 10% made from some cheap filler metal), and spend 1,111 gold coins back into the economy with the same amount of gold. They do look pretty similar to most people, but some discerning people will notice. Years later, if that’s not enough, he could re-melt them and make them 80% gold, and spend 1,250 of them into the economy…

At first, these slightly-debased coins would be treated as how they were before, but as the coins are increasingly debased, it would become obvious. Peoples’ savings would decline in value, as they found over time that their stash of gold and silver was only fractional gold and silver. Foreign merchants in particular would be quick to demand more of these debased gold coins in exchange for their goods and services.

Gold-backed paper currencies and fiat currencies are the modern version of that, and so the debasement can happen much faster.

At first, fiat currencies were created temporarily, in times of war. After the shift from commodity money to gold-backed paper, the gold-backing would be briefly suspended as an emergency action for a number of years, and then re-instated (usually with a significant devaluation, to a lower amount of gold per unit of currency, since a lot of currency was issued during the emergency period).

This is a faster and more efficient way to devalue a currency than to actually debase the metal. The government doesn’t have to collect everyone’s coins and re-melt them. Instead, everybody is holding paper money that they trust to be redeemable for a certain amount of gold, and the government can break that trust, suspend that redeemability, print a ton of paper money, and then re-peg that paper money such that each unit of paper currency is redeemable for a much smaller amount of gold, before people realize what is happening to their savings.

That method instantly debases peoples’ money while they continue to hold it, and can be done overnight with the stroke of a pen.

Throughout the 20th century, this tactic spread around the world like a virus. Prior to paper currencies, governments would run out of fighting capability if they ran low on gold. Governments would use up their gold reserves and raise additional war taxes, but there were limits in terms of how much gold they had and how much they could realistically tax for unpopular wars before the population would rebel. However, by having all of their citizens on a gold-backed paper currency, they could devalue everyone’s savings for the war without an official tax, by printing a lot of money, spending it into the economy, and then eliminating or reducing the gold peg before people knew what was happening to their money.

This allowed governments to fight much larger wars by extracting more savings from their citizens, which led their international opponents to debase their currencies with similar tactics as well if they wanted to win.

Ironically, the fact that fiat currencies have no cost to produce, is what gave them the biggest cost of all.

Bretton Woods and the Petrodollar

After World War I, and throughout the tariff wars and World War II period thereafter, many countries went off the gold standard or devalued their currencies relative to gold.

John Maynard Keynes, the famous economist, said in 1924:

In truth, the gold standard is already a barbarous relic.

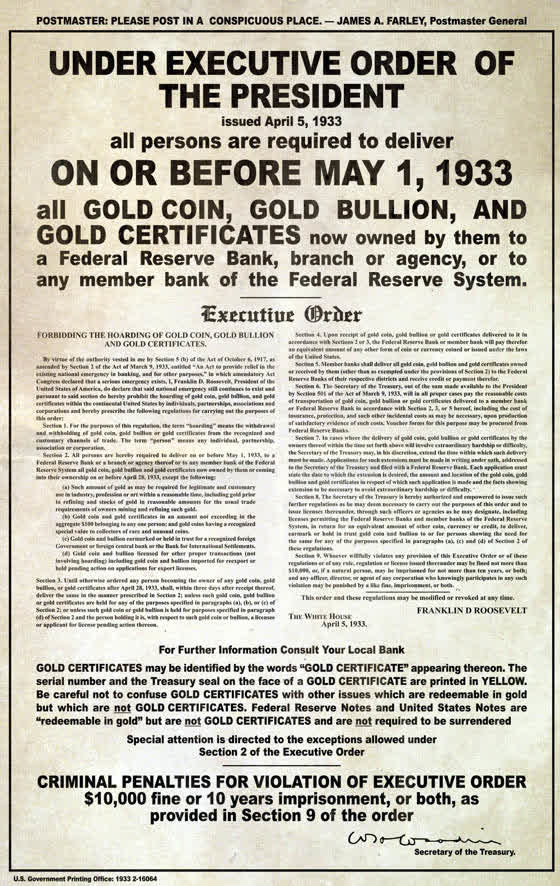

By 1934, gold was made illegal to own. It was punishable by up to 10 years in prison for Americans to own it. The dollar was no longer redeemable for gold by American citizens, although it was still redeemable for official foreign creditors, which was an important part of maintaining the dollar’s credibility.

US Government, Public Domain

Shortly after Americans were forced to sell their gold to the government in exchange for dollars, the dollar was devalued relative to gold, which benefited the government at the expense of those who were forced to sell it.

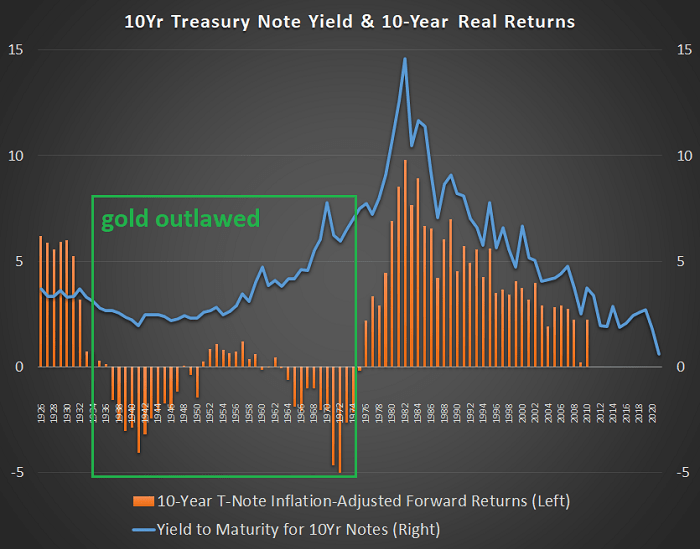

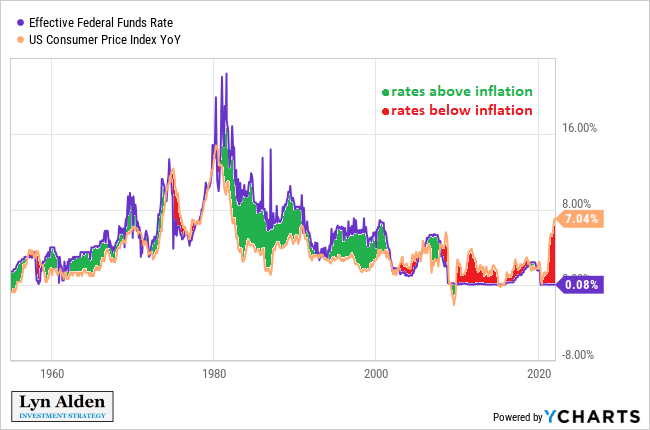

It remained illegal for Americans to own gold for about four decades until the mid-1970s. Interestingly enough, that overlapped quite cleanly with the period where US Treasuries underperformed inflation. Basically, the main release valve that people could turn to instead of cash or Treasuries as savings assets, was made illegal to them:

Lyn Alden

It’s rather ironic- gold was a “barbarous relic” and yet apparently had to be confiscated and pushed out of use by the threat of imprisonment, and hoarded only by the government during a period of intentional currency devaluation. If it were truly such a relic, it would have fallen out of usage on its own and the government would have had little need to own any.

Making gold illegal to own was hard to enforce though. There were not many prosecutions for it, and it’s not as though authorities went door-to-door looking for it.

By 1944 towards the end of World War II after most currencies were sharply devalued, the Bretton Woods agreement was reached. Most countries pegged their currency to the dollar, and the United States dollar remained pegged to gold (but only redeemable to large foreign creditors, not American citizens). By extension, a pseudo gold standard was temporarily re-established.

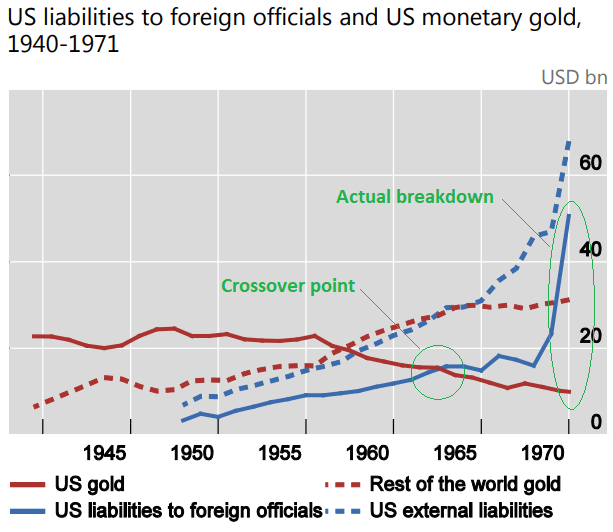

This lasted only 27 years until 1971, when the United States no longer had enough gold to maintain redemption for its dollars, and thus ended the gold standard for itself and most of the world. There were too many dollar claims compared to how much gold the US had:

BIS Working Papers No 684

The Bretton Woods system was poorly-constructed from the beginning, because domestic and foreign banks could lend dollars into existence without having to maintain a certain amount of gold to back those dollars. The mechanism for dollar creation and gold were completely decoupled from each other, in other words, and so it was inevitable that the quantity of dollars in existence would quickly outpace how much gold the US Treasury had in its vaults. As the amount of dollars multiplied and the amount of available gold did not, any smart foreign creditor would begin redeeming dollars for gold and draining the Treasury’s vaults. The Treasury would be quickly drained of its gold until they either sharply devalued the dollar peg or ended the peg altogether, which they did.

Since that time, over 50 years now, virtually all countries in the world have been on a fiat currency system, which is the first time in history this has happened. Switzerland was an exception that kept their gold standard until 1999, but for most countries it has been over 50 years since they were on it.

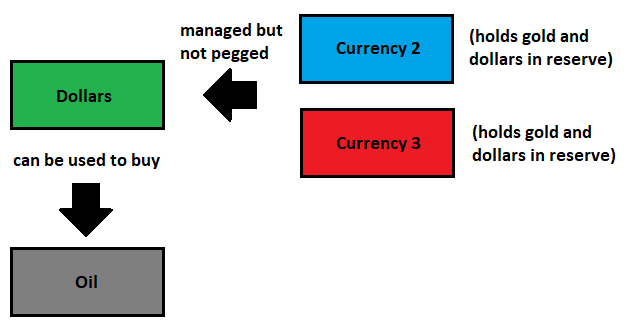

However, the US dollar still has a vestige of commodity-backing, which is part of what kept this system together for so long. In the 1970s, the US made a deal with Saudi Arabia and other OPEC countries to only sell their oil in dollars, regardless of which country was buying. In return, the US would provide military protection and trade deals. And thus the petrodollar system was born. We’ve had to deal with the consequences of this awkward relationship ever since.

While the dollar was not pegged to any specific price of oil in this system, this petrodollar system made it so that any country in the world that needed to import oil, needed dollars to do so. Thus, universal demand for dollars was established, as long as the US had enough military might and influence in the Middle East to maintain the agreement with the oil exporting nations.

Other countries continued to issue their own currencies but held gold, dollars (mainly in the form of US Treasuries), and other foreign currency assets as reserves to back up their currencies. Most of their currencies were not pegged to any specific dollar, oil, or gold value during this time, but having a large reserve that they could use to actively maintain the strength of their currency was a key part of why global creditors would accept their currency.

The biggest benefit from the petrodollar system, as analyst Luke Gromen has argued, is that it contributed to the US’s Cold War victory over the Soviet Union during the 1970s and 1980s. The petrodollar agreement and associated military buildup to enforce it was a strong chess move by the US to gain influence over the Middle East and its resources. However, Gromen also argues that when the Soviet Union fell in the early 1990s, the US should have pivoted and given up this system to avoid ongoing structural trade deficits, but did not, and so its industrial base was aggressively hollowed out. Since then, China and other countries have used the system against the US, and the US also bled out tremendous resources trying to maintain its hegemony in the Middle East with its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

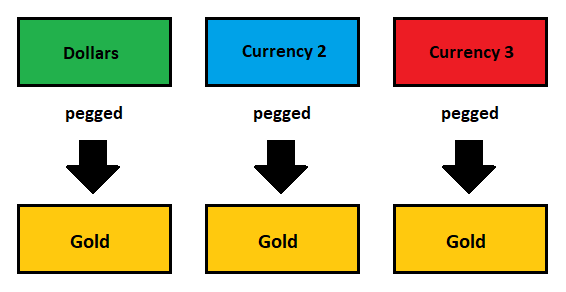

An international gold standard looks like this, with each major country pegging its own currency to a fixed amount of gold and holding gold in reserve, for which it was redeemable to its citizens and foreign creditors:

Lyn Alden

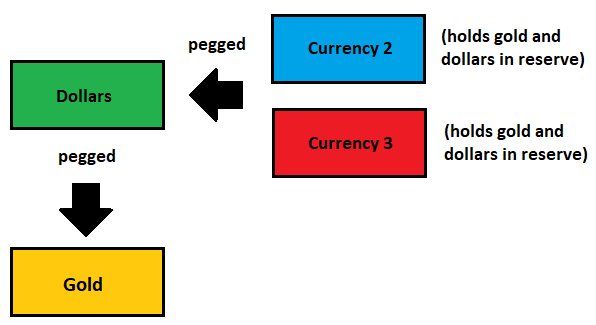

The Bretton Woods pseudo gold standard involved the dollar being backed by gold, but only redeemable to foreign creditors in limited amounts. Foreign currencies pegged themselves to the dollar, and held dollars/Treasuries and gold in reserve:

Lyn Alden

The petrodollar system made it so that only dollars could buy oil imports around the world, and so countries globally hold a combination of dollars, gold, and other major currencies as reserves, with an emphasis on dollars. If countries want to strengthen their currencies, they can sell some reserves and buy back their own currency. If countries want to weaken their currencies, they can print more of their currency and buy more reserve assets.

Lyn Alden

Over time, that demand for dollars was broadened via trade and debt. If two countries trade goods or services, they often do so in dollars. When loans are made internationally, they are often done so in dollars, and the world now has over $13 trillion in dollar-denominated debt, owed to all sorts of places including lenders in Europe and China. All of that dollar-denominated debt represents additional demand for dollars, since dollars are required to service that debt. Basically, the petrodollar deal helped initiate and maintain the network effect at a critical time, until it became rather self-sustaining.

This system gives the United States considerable geopolitical influence, because it can sanction any country and cut it off from the dollar-based system.

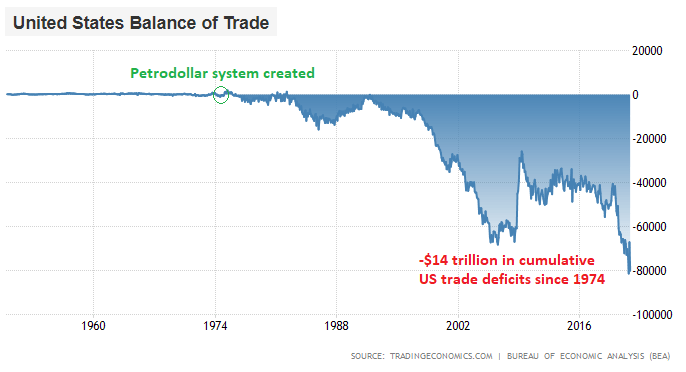

One of the key flaws of the petrodollar system, however, is that all of this demand for the dollar makes US exports more expensive (less competitive) and makes imports less expensive, and so the US began running structural trade deficits once we established the system, totaling over $14 trillion in cumulative deficits as of this writing. From 1944-1971 the US drew down its gold reserves in order to maintain the Bretton Woods dollar system, whereas from 1974-present, the US instead drew down its industrial base to maintain the petrodollar system.

Trading Economics

As the FT described in a clever article back in 2019, this petrodollar system ironically gave the United States a form of Dutch Disease. For those who aren’t familiar with the term, Investopedia has a good article on Dutch Disease. Here’s a summary:

The term Dutch disease was coined by The Economist magazine in 1977 when the publication analyzed a crisis that occurred in the Netherlands after the discovery of vast natural gas deposits in the North Sea in 1959. The newfound wealth and massive exports of oil caused the value of the Dutch guilder to rise sharply, making Dutch exports of all non-oil products less competitive on the world market. Unemployment rose from 1.1% to 5.1%, and capital investment in the country dropped.

Dutch disease became widely used in economic circles as a shorthand way of describing the paradoxical situation in which seemingly good news, such as the discovery of large oil reserves, negatively impacts a country’s broader economy.

As the FT argues (correctly in my view), making virtually all global oil priced in dollars basically gave the United States a form of Dutch Disease. Except instead of finding oil or gas, we engineered a system so that every country needs dollars, and so we need to export a lot of dollars via a structural trade deficit (and thus, the dollar as a global reserve asset basically served the role of a big oil/gas discovery).

This system, much like the Netherlands’ natural gas discovery, kept US currency persistently stronger at any given time than it should be on a trade balance basis. This made actual US exports rather uncompetitive, boosted our import power (especially for the upper classes) and prevented the US balance of trade from ever normalizing for decades.

Japan and Germany became major exporters at our expense, and for example, their auto industries thrived globally while the US auto industry faltered and led to the creation of the “Rust Belt” across the midwestern and northeast part of the country. And then China grew and did the same thing to the United States over the past twenty years; they ate our manufacturing lunch. Meanwhile, Taiwan and South Korea became the hubs of the global semiconductor market, rather than the United States.

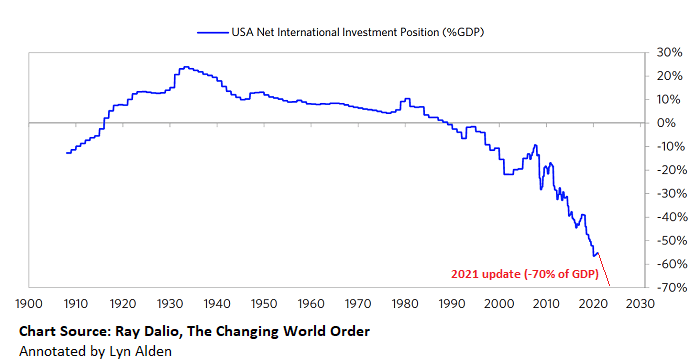

That petrodollar system is starting to crack under its own weight, as trade deficits have collected into a massively negative net international investment position for the US, and the US has more wealth concentration than the rest of the developed world because we hollowed out a lot of our blue collar workforce specifically. This causes rising political tensions and desires (so far unsuccessful) to reduce the trade deficit and rebuild our industrial base. Foreigners take their persistent dollar surpluses and buy productive US assets with them like stocks, real estate, and land. In other words, the US sells its appreciating financial assets in exchange for depreciating consumer goods:

Ray Dalio, The Changing World Order

My article on the petrodollar system went into additional detail on the history of the US dollar as the global reserve currency, from the pre-Bretton Woods era to the petrodollar system.

Potential Post-Petrodollar Designs

There are proposals by policymakers and analysts to rebalance the global payments system, and the changing nature of geopolitics is pointing in that direction as well.

For example, Russia began pricing its oil partly in euros over the past few years, and China has put considerable work into launching a digital currency that may expand their global reach, at least with some of their most dependent trade partners. The United States is no longer the biggest commodity importer, and its share of global GDP continues to decrease, which makes the existing petrodollar system less tenable.

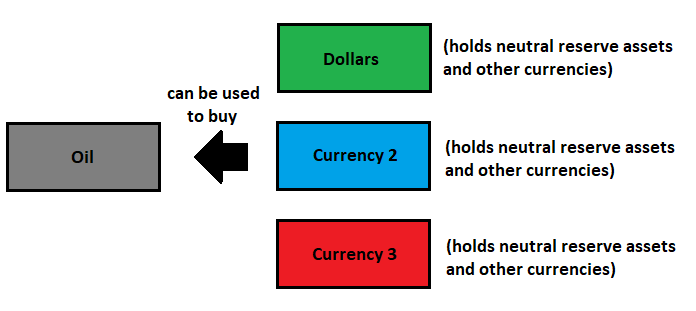

If several large fiat currencies can be used to buy oil, then the model looks more like this (and many tertiary currencies would manage themselves relative to these main currencies that have the scale and influence to buy oil and other foreign goods):

Lyn Alden

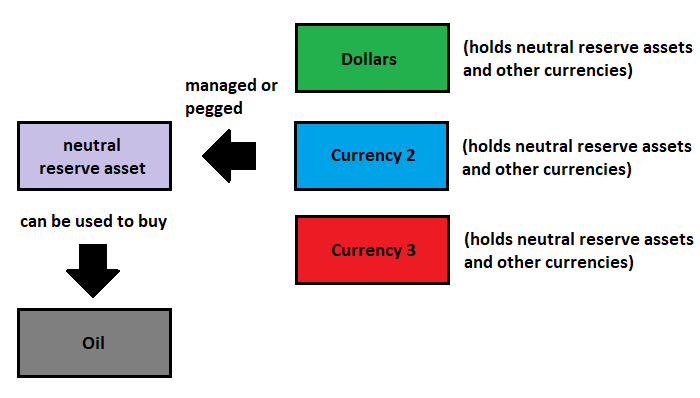

If a major scarce neutral reserve asset (e.g. gold or bitcoin or digital SDRs or something along these lines, depending on your conception of where trends are going over the next decade or two) is used as a globally-recognized form of money, then a decentralized model can also look like this:

Lyn Alden

Overall, it’s clear that the trend in global payments is towards digitization and decentralization away from one single country’s currency, but it’s unclear precisely how the next system will turn out and on what timeline it will change. It continues to be a subject that I analyze closely for news and data.

Price Inflation from a Negative Baseline

The long arc of human history is deflationary. As our technology improves over time, we become more productive, which reduces the labor/resource cost of most goods and services. This is particularly true over the past couple centuries as humanity exponentially tapped into dense forms of energy. Prior to that, our rate of productivity growth was much slower.

For an example of productivity, people used to farm by hand. By harnessing the utility of work horses and simple equipment, it empowered one person to do the work of several people. Then, the invention of the tractor and similar advanced equipment empowered one person to do the work of ten or more people. As tractor technology got bigger and better, this figure probably jumped to thirty or more people. And then, we can imagine a fleet of self-driving farming equipment allowing one person to do the work of a hundred people. As a result, a smaller and smaller percentage of the population needs to work in agriculture in order to feed the whole population. This makes food less expensive and frees up everyone else for other productive pursuits.

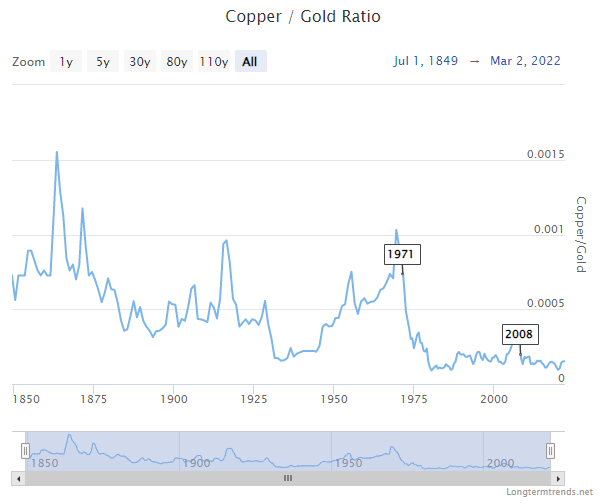

Gold has historically appreciated against most other commodities over time, like an upward sine wave. Alternatively, we can say that most commodities depreciated in price against gold like a downward sine wave. For example, there are inflationary cycles where copper increases in price compared to gold, but over multiple decades of cycles, gold has steadily appreciated against copper. For agricultural commodities that are less scarce, the trend is even stronger.

Here’s a chart of the copper-to-gold ratio showing its structural decline and cyclical exceptions since 1850, for example:

Long Term Trends

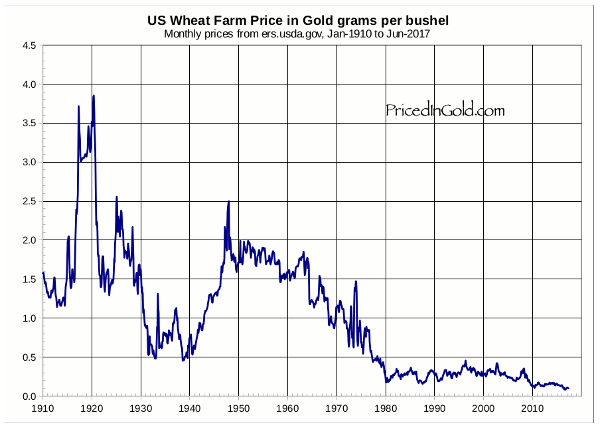

And here’s wheat priced in gold since 1910:

Priced in Gold

This is because over time, our advancing technology has made us more efficient at harvesting those other commodities. However, gold’s extreme scarcity and rather strict stock-to-flow ratio of over 50x has made it so that our technology advancements in finding and mining gold are offset by the fact that we’ve already mined the “easy” gold deposits and the remaining deposits are getting deeper and harder. We never truly get more efficient at retrieving gold, in that sense. It’s a built-in ongoing difficulty adjustment.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s USA, which is when the country became a rising power globally, the country was on a gold standard and in a period of structural deflation. Prices of most things went down because land was abundant and huge advancements in technology during the industrial age made people far more productive.

An even more extreme example would be television prices over the past five decades. Moore’s law, industrial automation, and labor offshoring has made televisions exponentially better and cheaper over time, especially when priced in gold. Similarly, cell phones decades ago were very large, basic, and expensive toys for the wealthy. Now, many people in the poorest regions of the world have powerful smartphones as a normal course of life. They have supercomputers in their pockets.

Overall, we can say that the baseline inflation rate is some negative number (aka deflation), and how negative it is at any given time depends on the pace of technological advancement. Baseline inflation only becomes a positive number if we are backtracking in some way, and thus encountering more scarcity and less abundance. This could be due to malinvestment or war, for example.

By holding the most salable good (such as gold, historically), your purchasing power gradually appreciates over time because the labor/resource cost of most other things goes down whereas that salable good retains most or all of its scarcity and value. The vast majority of commodities, products, and services structurally decrease in price gradually relative to your strong store of value.

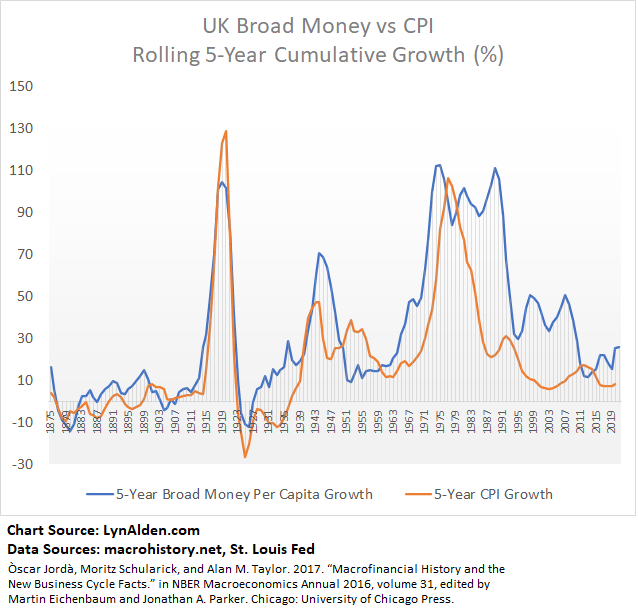

One way to measure this is by looking at the broad money supply per capita over time relative to the consumer price index. Here’s a chart of their 5-year rolling average growth rates for the United Kingdom:

Lyn Alden

We can see that there is usually a positive gap between broad money supply growth per capita, and consumer prices. Broad money supply per capita increased by an average of 5.3% per year during this 150+ year period, while a basket of goods and services increased by an average of only 3.1%. In other words, monetary inflation is usually a bit faster than price inflation.

In a very rough sense by this way of looking at it, real productivity growth was about 2.2% per year, which is the difference between these figures. What this means is that in any given year, the resource/labor costs of a broad basket of goods and services goes down by an average of 2.2% due to technological progress, but the amount of money that people have goes up by 5.3%, and as such, actual prices go up by only 3.1%.

So, price inflation is not 3.1% from a baseline of zero; it’s 5.3% from a baseline of -2.2%. Actual resource costs for goods and services go down most years rather than stay flat, but due to our inflationary monetary framework, they go up in price anyway.

The reason this is only a rough measure is because 1) the CPI basket changes over time and may not be fully representative and 2) money supply can become more concentrated or less concentrated over time and thus does not always reflect the buying power of the median person. There is no way to directly measure technological deflation; it can only be estimated.

Another way to check this is to simply see to what extent gold appreciated in price against the British pound, and the answer is about 4.0% per year over this same 150+ year time period. Gold appreciated in price faster than the CPI basket inflation rate by about 0.9% per year (the difference between 4.0% and 3.1%, which compounds quite a bit over a century), and can buy you a bit more copper, oil, wheat, or many other goods and services than it could 50, 100, or 150 years ago, unlike the British pound which buys you a lot less than it used to. Higher-quality and scarcer goods like meat have roughly kept up with the price of gold (although you can’t store meat for very long), and select few assets like the absolute best/scarcest UK property locations may have appreciated a bit faster than gold (although they required continued maintenance costs along the way which makes up for that difference).

The takeaway from this section is that the growth in the broad money supply per capita is the “true” inflation rate. However, the baseline that we measure it against is not zero; it’s a mildly negative number which we can’t precisely measure, but that we can estimate and infer, that represents ongoing increases in productivity due to technology. Prices of most things stay relatively stable or preferably keep going down as priced in the most salable good (such as gold, historically) over the long run, but go up in most years when measured in a depreciating and weaker unit of account such as the British pound.

The MMT Description of Fiat Currency

Some economists disagree with the commodity view of money, and argue that money originates with the government. This is called Chartalism, and its origins go back more than a century.

Decades ago, Warren Mosler and others resurfaced this idea, into what is now popularly known as Modern Monetary Theory or MMT.

I have often felt that Mosler describes the case for that school of thought well. He doesn’t sugar-coat things, and instead speaks very directly:

Start with the government trying to provision itself and how does it do it. There are different ways to do it throughout history. One way is just to go out and take slaves. Another way the British did is they provisioned their navy by going to bars late at night and dragging them onto ships. It’s called impressing sailors.

We pretend to be more civilized as I like to say, and we use a monetary system. So how does a government do it? Clean sheet of paper, what you do, is you establish a tax that is payable in something that people don’t have. So what you want to do is transfer resources from the private sector to the public sector. You want people who are out there doing whatever they are doing, to suddenly be working for the government. You need soldiers, you need police, you need health workers, you need people in education. How do you get these people out of the private sector and into the public sector?

First thing you do is you levy a tax. You need a tax liability, and it has to be coercive. And for this example I’ll use a property tax. You put a tax on everybody’s house, and you make it payable in your new unit of account, your new unit, your thing, your tax credit, the thing that is used to pay the tax. The dollar, the yen, or the euro- they are all tax credits.

What has happened is, you’ve created sellers of real goods and services who now need your tax credit, or they’re going to lose their house. You’ve created unemployment- people looking for paid work. Unemployment is not about people looking to volunteer at the American Cancer Society; it’s about people looking for work because they need or want the money. And the problem with government when you want to provision yourself is that there’s no unemployment. No unemployment in terms of your currency; there may be people willing to work for other things but not for your currency. You need unemployment in terms of your currency, looking to earn your unit of account.

So you levy a tax, now people need your unit of account, all of these people show up looking for work, all of those people are unemployed. You now hire the unemployed that your tax created, and they are now provisioning your government.

-Warren Mosler, 2017 MMT Conference

I also liked this description, where he explained his view in an economic debate:

The way we do it, is we slap on a tax for something that nobody has, and in order to get the funds to pay that tax, you have to come to the government for it, and so that way the government can spend its otherwise worthless currency and provision itself.

Now the way I like to explain that, is I’ll take out my business card here. Now I’ll ask this room does anybody want to buy- and this is called “how to turn litter into money”- does anybody want to buy one of these cards for a hundred dollars? No? Okay. Does anybody want to stay after hours and help vacuum the floor and clean the room and I’ll give you my cards? No? Alright. Oh by the way there’s only one door out of here and my guy is out there with a 9mm (handgun) and you can’t get out of here without one of these cards.

Can you feel the pressure now? You’re now unemployed! In terms of my cards, you were not unemployed before. You were not looking for a job that paid in my cards. Now you’re looking for a job that pays in my cards, or you’re looking to buy them from someone else that will take a job that pays in my cards.

[…]

The difference between money and litter is whether there’s a tax man [outside that door]. The guy with the 9mm is the tax man. If he can’t enforce tax collection, the value of the dollar goes to zero.

-Warren Mosler, 2013 MMT vs Austrian Debate

Nobel-laureate economist Paul Krugman put it rather similarly back in 2013:

Fiat money, if you like, is backed by men with guns.

Of course, we could just as easily ask, since the government is using force to collect taxes to provision itself, why can’t it just collect commodity money like gold with a tax, and then spend that gold to acquire its necessary provisions? Why does it need to issue its own paper currency and then tax it back?

The answer is that it doesn’t have to, but it wants to. By issuing its own currency, it profits from seigniorage, which is the difference between the face value of the money and the cost to produce and distribute it. It is, basically, a subtle inflation tax that compounds over time.

A weak government, with an economy that can’t provision most of its needs, often fails to maintain a workable fiat currency for very long. People start using alternative monies out of necessity even if the government supposedly disallows them from doing so. This happens to many developing countries. Billions of people in the world today have experienced the effects of hyperinflation or near-hyperinflation within the past generation. It’s unfortunately quite common.

However, developed countries have been more successful at maintaining seigniorage over the past five decades of the fiat system. Their currencies all lost 95% to 99% of their purchasing power over time, but it was usually gradual rather than abrupt. The system is not without its cracks as previously-discussed, but it’s certainly the most comprehensive fiat currency system ever constructed.

When optimized skillfully, a fiat currency has low volatility year-to-year, in exchange for gradually losing value over the long run. By being actively managed with taxes, spending, and central bank reserve management (creating or destroying currency in exchange for reserve assets), policymakers try to maintain a low and steady inflation rate, meaning a mild and persistent decline in the purchasing power of their currency.

A strong government can force the use of its currency over all other types of monies within its borders, at least for a medium of exchange (not necessarily a store of value), by taxing other types of transactions, and by only accepting its fiat currency as a form of payment for taxes. They can make things like gold, silver, and bitcoin less convenient as money, for example, by making each transaction with it a taxable event in terms of capital gains. If push comes to shove, they can also try to ban those things with threat of force.

The Monetization of Other Assets

Although most of us today are used to it, fiat currency has been a polarizing and inherently political subject ever since the world went onto this petrodollar standard five decades ago.

Mainstream media and economists, however, quickly adopted it as canon and rather unquestionable. For decades now, it has been the case that if someone thinks money shouldn’t be fiat currency, they’re kind of considered a kook and not taken seriously. This kind of vibe:

History Channel (meme)

But when you step back and think about it from first principles, this period in history is really unusual. It’s a historical aberration, and like a fish in water doesn’t even notice the water, the monetary system we operate with now seems totally normal to us.

Never before, in thousands of years of human history, has the entire world been using a money that has no resource cost or constraint. It’s an experiment, in other words, and we’re five decades into it. Many would consider it a good experiment, while others consider it a bad one, but it’s not as though it is inevitable, or the only possible outcome from here. It’s simply what we have now, and who knows what things will look like in another five decades.

To put it into perspective, this international monetary system based around centrally-managed fiat currency is only 16 years older than me. My father was 36 when the US went off the gold standard. When I grew up, after a period of financial hardship, I began collecting gold and silver coins as a kid; my father gave me silver coins as savings each year.

The Swiss dropped their gold standard when I was twelve years old, which was six years after Amazon was founded, and three years before Tesla was founded. The fiat/petrodollar standard is only four times older than bitcoin, and only two times older than the first internet browser. That’s pretty recent when you think about it like that.

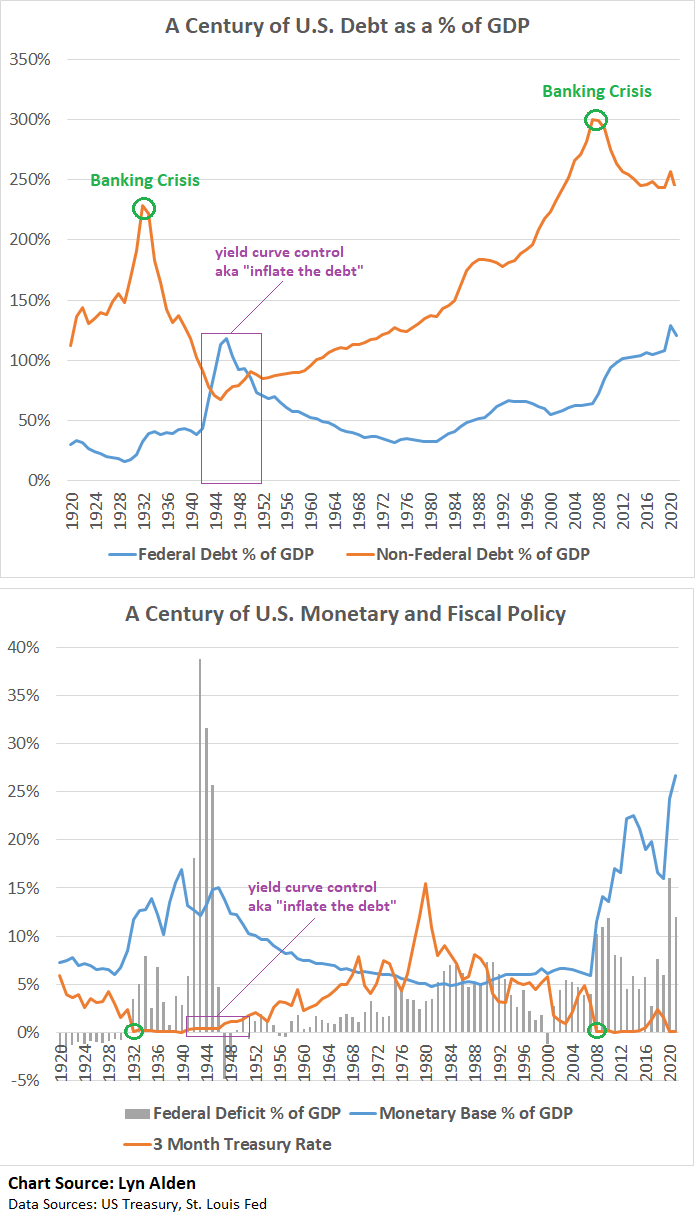

Ever since the world has been on the fiat/petrodollar standard, debt as a percentage of GDP has skyrocketed to record levels and seems to be getting unstable. Considering where we are in the long-term debt cycle, investors would do well to be creative with how they envision the future. Don’t take the past 40-50 years for granted and assume that’s how it’ll always be, whether for money or anything else. We don’t know what money will look like 50 years from now.

The last time we were in a similar debt and monetary policy situation was the 1930s and 1940s, where currency devaluations and war occurred. That doesn’t mean those things have to happen, but basically, we’re in a very macro-heavy environment where structural currency changes tend to occur.

Lyn Alden

One of the results of fiat currency, especially towards the later stages of this five decade experiment since the 1970s, is that more people have begun to treat cash like a hot potato. We instinctively monetize other things, like art, stocks, home equity, or gold. The ratio of home prices to median income has gone up a lot, as well as the ratio of the S&P 500 to median income, or a top-notch piece of art to median income.

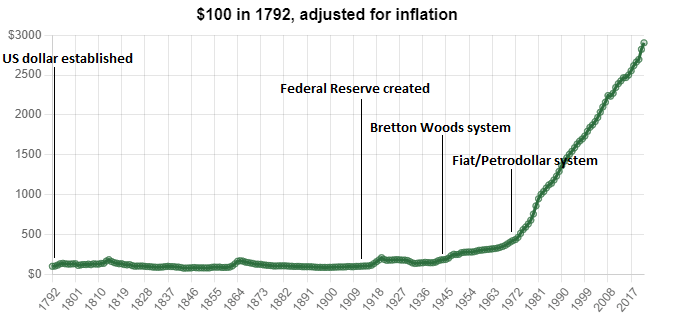

This chart shows the loss of purchasing power of the U.S. dollar since the Coinage Act of 1792, which is when the US dollar and the US Mint were created:

Ian Webster

It currently takes nearly $3,000 to have as much purchasing power as $100 bought in 1792. From 1792 to 1913, the dollar’s purchasing power oscillated mildly around the same value, with over 120 years of relative stability. From 1913 onward, the policy changed and the dollar has been in perpetual decline, especially after it completely dropped the gold peg in 1971.

And it’s actually worse today than during most of this 1971-2022 fiat/petrodollar period, because interest rates aren’t keeping up with inflation rates anymore. The fiat system is getting less stable due to so much debt being in the system, which disallows policymakers from raising interest rates higher than the prevailing inflation rate.

YCharts

Basically, for lack of good money in this fiat currency petrodollar era, especially in the post-2009 era with interest rates below inflation rates, we monetize other things with higher stock-to-flow ratios and treat them as stores of value.

In China, consumers aggressively monetize real estate. It became normal for families to own multiple homes. In the United States, consumers aggressively monetize stocks. We plow a percentage of each paycheck into broad equity indices without analyzing companies or doing any sort of due diligence, treating that basket of stocks as simply a better store of value than cash regardless of what is inside.

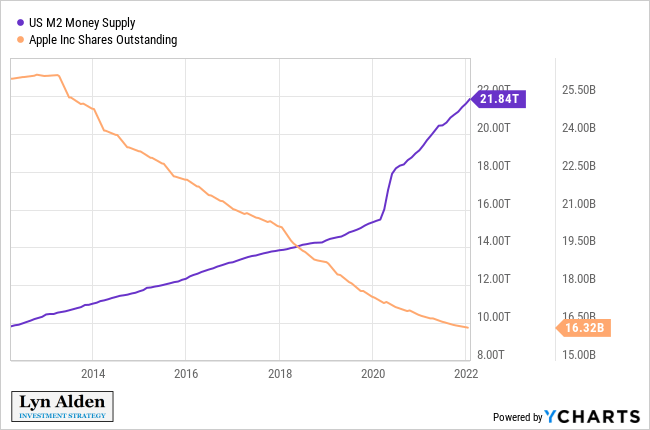

We can ask, for example, would we rather own dollars that went from 10 trillion in quantity ten years ago to 22 trillion today and pay basically no yield to own them, or Apple shares that went from 26 million shares ten years ago to 16 million shares today and also pay basically no yield to own it? Is the dollar better money, or is a diverse collection of fungible corporate shares better money, when it comes to storing value with a 5+ year time horizon?

YCharts

This monetization of non-money securities and property opens us up to more volatility, more leverage, less liquidity, less fungibility, and more taxable events. Basically, rather than investments being special things we make with careful consideration, we shovel most of our free capital into hundreds of index investments that we don’t even analyze, since who would hold currency for any significant length of time? Fungible pieces of corporations become our money, at least for the “store of value” portion of what money is, in large part because they pay higher earnings/dividend yields than bank/bond yields and many of them decrease in quantity (deflationary) rather than constantly increase in quantity.

Some technologists, like Jeff Booth, have argued that this system of perpetual currency debasement has a negative impact on the environment because it encourages us to spend and consume on short-sighted depreciating trinkets and malinvestment more than we would if our money appreciated in value over time like it used to. With appreciating money, we would be more selective with our purchases.

Proponents of the fiat system argue that it smooths out economic downturns and allows for counter-cyclical investment and stimulus. By having a flexible monetary base, policymakers can increase or decrease the supply of money in order to provide a balancing force against credit cycles and industrial output capacity. In exchange for a persistently declining value of currency, we get a more stable currency on a year-to-year basis.

In addition, proponents of the system also argue that the system encourages more consumption and consider that to be a good thing because it keeps GDP up. By keeping people on a constant treadmill of currency debasement, it forces them to spend and invest rather than to save. If people begin to save, these policymakers often view it as “hoarding” or a “global savings glut” and consider it to be a problem. Monetary policy then is adjusted to convince people to save less, spend more, and borrow more.

From a developing market standpoint, the fiat/petrodollar standard contributes to massive booms and busts because a lot of their debt is denominated in dollars, and that debt fluctuates wildly in strength depending on the actions of US policymakers. Developing countries are often forced to tighten their monetary policy during a recession in order to defend their currency, and thus while the US gets to provide counter-cyclical support for its own economy, developing countries are forced to be pro-cyclical, contributing to a vicious cycle in their economies during recessions. In this view, the fiat/petrodollar system can be considered a form of neocolonialism; we push most of the costs of the system out into the developing countries in order to maximize the stability for the developed world.

Overall, the fiat system is showing more instability lately, and investors have to navigate a challenging environment of structurally negative inflation-adjusted cash and bond yields, along with many high asset valuations in equities and real estate.

Sovereign International Reserves

As countries accumulate trade surpluses, they keep those gains in sovereign international reserves. This represents the pool of assets that a country’s central bank can draw upon to defend the country’s currency if needed. The more reserves a country has relative to its GDP and money supply, the more defense it has against a meltdown in its fiat currency. The country can sell these reserves and buy back its own currency to support its currency per-unit value. The currency may not be backed up by gold at a redeemable rate, but it’s backed up by diverse assets as needed if its starts to rapidly lose value.

The world collectively has about $15 trillion USD-equivalents worth of official sovereign reserves. Less than $2.5 trillion of that is gold, with more than $12.5 trillion held as fiat reserves (dollars, euros, yen, franks, etc). Fiat reserves consist of government bonds and bank deposits, and can be easily frozen by the countries that issue them. In addition, many gold holdings are not held within the country, but instead are held in New York or London on their behalf.

Thus, the vast majority of sovereign official reserves, are permissioned assets rather than permissionless assets. They are non-sovereign; able to be frozen by foreign nations. War crystalizes this fact.

In February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. Russia had $630 billion USD-equivalents of sovereign international reserves prior to the war, representing decades of accumulated trade surpluses as sovereign savings to underpin their currency. Of this $630 billion, $130 billion consisted of gold, and the other $500 billion consisted of fiat currency and bonds. Of that $500 billion, maybe $70-$80 billion consisted of Chinese fiat assets, and the other $400+ billion consisted of European and other fiat assets. Europe subsequently froze that $400+ billion in Russian fiat assets in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which is equivalent to over 20% of Russian GDP and over five years of Russian military spending; an utterly massive economic confiscation. Russia is currently in a financial crisis, and it remains to be seen if they can exert enough commodity/military pressure to have their reserves unfrozen.

Some could argue that it’s a good thing that countries hold their reserves in each other’s assets and thus can be frozen. Along with trade sanctions, this practice gives countries another lever with which to control each others’ behavior away from extremes (such as war). We’re all interdependent to one degree or another anyway. But from a pragmatic point of view, countries tend to want to reduce their vulnerabilities and external risks where possible, and that can include minimizing the ability of their stored-up central bank reserves to be confiscated or frozen by other countries.

I began writing this longform article months ago, in late 2021. Things have accelerated since then, and for example the WSJ ran an article in early March 2022 called “If Russian Currency Reserves Aren’t Really Money, the World is in for a Shock.” Here’s the opening paragraph:

“What is money?” is a question that economists have pondered for centuries, but the blocking of Russia’s central-bank reserves has revived its relevance for the world’s biggest nations—particularly China. In a world in which accumulating foreign assets is seen as risky, military and economic blocs are set to drift farther apart.

What is money?

Well, the answer to that question ties into the difference between currency and money. Currency is some other entity’s liability, and they can choose whether or not to honor that particular liability. Money is something that is intrinsically valuable in its own right to other entities, and that has no counterparty risk if you custody it yourself (although it may have pricing risk related to supply and demand). In other words, Russia’s gold is money; their FX reserves are currency. The same is true for other countries.

Fiat currency and government bonds have no intrinsic value; they represent indirect claims of value that can be blocked and confiscated. Gold has value; it’s sufficiently fungible and due to its physical properties, various entities would accept gold at the current market value. It can be self-custodied and no external nation can shut it off.

Currency acts like money most of the time until, one day, it doesn’t.

Fiat Summarized

Overall, the key feature or bug of fiat currency (depending on how you look at it) is its flexible supply and its ability to be diluted. It allows governments to spend more than they tax, by diluting peoples’ existing holdings. With this feature, it can be used to re-liquify seized-up financial situations, and stimulate an economy in a counter-cyclical way. In addition, its volatility can be minimized compared to commodity monies most of the time through active management, in exchange for ensuring gradual devaluation over time.

When things go wrong, however, fiat currency can lose value explosively. Fiat currency tends to incentivize running bigger deficits (since spending doesn’t necessarily need to be taxed for), and generally requires some degree of hard or soft coercion in order to get people to use it over harder monies, although that coercion is often rather invisible to most people most of the time, until things go wrong. And its ability to be diluted can allow for longer wars, selective bailouts for influential groups, and other forms of government spending that aren’t always transparent to citizens.

The final part in this series will focus on digital forms of money. Stateless networks of money have now been developed (e.g. bitcoin), corporations have used blockchains to run fiat currency over blockchain rails (e.g. stablecoins), and a number of governments have launched more natively digital version of their fiat currencies (e.g. the e-CNY), and this will be explored in the final part.

Be the first to comment