remotevfx/iStock via Getty Images

Some of what is described here is about a microcap, a stock smaller than we would normally discuss here. I’m still using it partly because it’s an example of a larger point. Also, because the current microcap status is a function of a recent price decline, rather than something inherent to the stock. Microcaps can be dangerous to trade in.

The helium market

One of the things that people get wrong about helium is that it’s an inherently scarce resource. Not really, it’s the only non-radioactive element that we use which is continuously generated here on Earth. Having had my little snark – and this becomes important later when we discuss the market for it – yes, OK, in any useful time frames the supply is indeed limited.

In the past it has been supplied largely through the US Feds, that programme is now wound down and so we’re back to free market supply. There are a number of companies out there looking for it and some will undoubtedly find commercial deposits. I’ve talked about this with Global Helium and Helium One. What I’m really going to do here is explain why I’ve a problem with the market itself. Using Total as a good example of my little problem.

There’s nothing particularly wrong that I can see with this company. Sure, they’re small, but then a pure helium play is going to be small, it’s not exactly a huge market. It’s only recently to the OTC market but again, everyone’s got to start somewhere. They’re actually in production, they’re selling both methane and helium.

Sure, of course, things could go right for them, prices surge. They could go wrong, prices fall. Or there’s some disaster to the rigs or wells or all of the things that could prey upon a company. But the basic idea, let’s go looking for helium, we’ve found some, let’s extract it – sure, they’re doing fine.

So I’m not going to argue in favour of them, or against them, in that sense. What they are for me though is an example of one of the three ways of going looking for helium. This is in fact the old way, the known way, it works. The thing is, will it work when and if the new ways do?

The other way of putting this is that I think there’s a serious possibility of oversupply – and thus rock bottom prices – in the helium market. That makes me worry about pure play helium stocks. For it will be them that carry the brunt of any low prices – those producing just as a byproduct will miss the cash but won’t worry excessively. Note that this is always true in extraction markets.

One helium extraction method

One method is to do exactly what is being done by Total Helium. The way it’s been done for near a century now. Go drilling in the Hugoton Field – what used to feed the Fed’s supply – and get some gas which is pretty low grade by natural gas standards but which has a pleasing helium content.

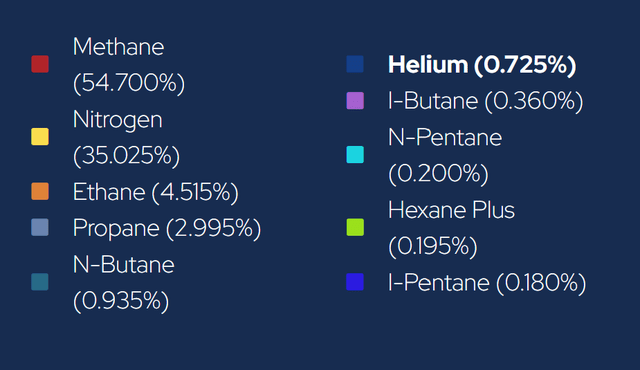

Gas contents from Total Helium (Total Helium)

There’s nothing terribly exciting about these contents. They’re pretty normal for this area and field in fact. That nitrogen level is a lot higher than anyone would be comfortable shipping off to actually be burnt of course, so some processing has to be done. Which is fine, because as you do that you end up capturing the helium with the nitrogen and thus making that cheaper to extract itself.

We also know that this is in fact profitable to do for we’ve many decades of experience both generally and in this field:

Helium also exists in concentrations as high as 8 percent in certain natural gases. Most U.S. helium-rich natural gas is located in the Hugoton-Panhandle field in Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas; the LaBarge field in the Riley Ridge area of Wyoming; and the federal facility in the Cliffside field near Amarillo, Texas (Figure 2.2). Generally, natural gas containing more than 0.3 percent helium is considered economic for helium extraction in the United States,

OK, great. We’re doing what we know can be done, in a field we know exists, know contains helium, using known techniques and, well, we know how to do this. Other than the usual risks of the management not running away with everything and so on (yes, a joke) then really what we’re left with is price risk for the output. For given the rise of fracking and that Henry Hub natural gas price we’re not going to be excited here if all we can actually sell is that rather low grade and nitrogen high natural gas.

We’re exposed, really, to helium price risk here.

Another method

Another helium production method is to go look for fields that are much richer in helium. That’s what, as I’ve said before, Helium One is doing. If you want the full details of the decision tree that’s here. Very briefly, helium comes from the radioactive breakdown of uranium and thorium. The gas collects, often enough, with natural gas. So, the desire is old U and Th containing rocks, with a hard cap above them producing reservoirs. The cap must be hard, for helium can get through layers that natural gas cannot. The Rukwa area of Tanzania seems to meet these conditions. There are initial indications that there are 10% helium gas pockets there. But how many of what size? That’s what is still being tested.

But clearly a 10% He gas supply is more fun and more profitable to process for He than a 0.7% one. If significantly large fields exist out there then the helium market is small enough that this could well impact the global price.

But both of these are being primary producers. Either known tech in a known producing area which is safe but possibly boring or prospecting for a much richer source with greater risk. But both are entirely reliant upon that helium price over time.

LNG

But here we come to the other possible production method. Recall above when I said that the base method is to process the helium out of natural gas? The method of doing that is successive waves of liquefaction. As you cool the gas then the propane, butane, methane (no, I’m not going to check the order there) come out as liquids and the other gases remain as, umm, gases. Keep going and eventually you’ll end up with only the helium left as “atmosphere” as it has the lowest boiling point of anything.

This is horribly energy intensive which is why there’s that cut off point of about 0.3% He in gas as being economic. Any less than that and it’s not worth the energy cost of trying to get it out. What the heck, stick it in the pipeline with the rest and so what?

Except, when we do liquefied natural gas then what are we doing? Clearly, we’re already cooling that methane down to where it’s liquid. Which means that we’ve already hugely concentrated the helium in that remnant atmosphere – what’s still gas after we’ve liquefied the propane, butane, methane. This makes the subsequent costs of going on to then produce helium much lower. Or, as these things work, we can go on to process He out of much lower concentrations economically as we’re already carrying large portions of the energy costs on our main process:

Although the helium content of the native gas produced at the Algerian facility is only 0.17 percent, economics are favorable since the gas is being converted to liquified natural gas for shipping, and the helium in it is more highly concentrated.

Which brings us to this (from: Helium in Natural Gas – Occurrence and Production):

In 2013, Air Liquide started up the world’s largest helium purification and liquefaction unit at Ras Laffan Industrial City, Qatar. The capacity of the unit is 38 million m3 of helium per year [20]. This alleviated the helium shortage that started in 2011.

Qatar is the world’s largest LNG exporter (well, at least until the US really gets into gear) and the location of that plant really is not a surprise.

Byproduct

It’s just one of these things that people making something as a byproduct require lower market prices than those going out looking specifically for that thing. Well, normally that is, unless the single product producer has a really, really, rich deposit. Because the entire point of byproduct production is that some large part of the costs are being carried by the main production line. These costs would be incurred anyway and the main production line isn’t going to operate, or not operate, because of the revenues or not from the byproduct.

Unless you’ve got a really rich gold ore you’re not going to beat the production costs of gold from a copper deposit. Simply because the copper’s going to be mined, that gold’s going to end up in the process anyway, whatever the gold price. If the germanium price collapses then Ge from coal fly ash will cease production, that from zinc mining of sphalerite will not. No one does mine gallium directly because there’s so much that can be gained from bauxite processing.

Why would you turn off a capture circuit if the revenue is near entirely additional and not collecting it doesn’t reduce costs much?

This is my problem

I agree that looking for, producing, helium from the same source we’ve been doing it from for a century looks like a good idea. This is what Total Helium is doing and I see no reason to fault them. They’re producing, great.

My problem is that I can’t, quite, see single product producers surviving here if as and when LNG producers add the helium capture circuits to their processes. I think we’re all agreed that LNG is going to be a larger part of the global energy supply for at least the next few decades.

Actually, by some estimates, helium is already in oversupply – more is being produced than used.

My view

I’m just not happy with the idea of being in a single product producer when the entire global industry is working toward producing that same single product as a byproduct of some other process. The point being that if there is a price squeeze – if – then it’s the single product producers who get squeezed. The byproduct producers will still be seeing additional revenue from production given that their cost base is covered by their main product. So, they’ll keep producing even as prices decline.

It is true that if demand holds up, or if supply doesn’t increase so much, then the single product producer is much more geared to that upside as well. But that’s not the way I see the risk running here.

The investor view

I can see Total Helium having some interesting stock price movements. Wouldn’t surprise at all if a quarter or two of actual production and revenue received produce a boost. My worry is as above. I have this harsh feeling that helium producers, as purely helium producers, are going to get squeezed by the expansion of the LNG industry.

I can’t see anything “wrong” with Total Helium but I worry about the market they’re in.

Be the first to comment