traveler1116

We argued in a previous article that there are already plenty of signs of inflation coming down and the Fed is at risk of tightening too much, with potentially dire economic consequences.

Here we will argue that inflation is mostly the result of a series of supply shocks and that there is little sign that these have triggered any of the two mechanisms through which they can become ingrained in the economy, and monetary tightening is ill-adapted to combat supply shocks.

One-off demand boost already reversing sharply

Many observers blame the Fed and/or the huge fiscal pandemic stimulus policies of the Trump and Biden administrations, and at first sight that seems plausible as they were inordinately large.

But they were also one-offs and have quickly reversed, and many tend to forget that we had inordinate monetary stimulus throughout much of the previous decade, without causing as much as a blip in inflation.

So monetary policy alone wasn’t likely to have ignited inflation, it needed an accomplice, which arrived in the form of outsized pandemic fiscal stimulus. Fiscal stimulus is very powerful at very low-interest rates, so there is little doubt this has been a factor in creating inflationary pressures.

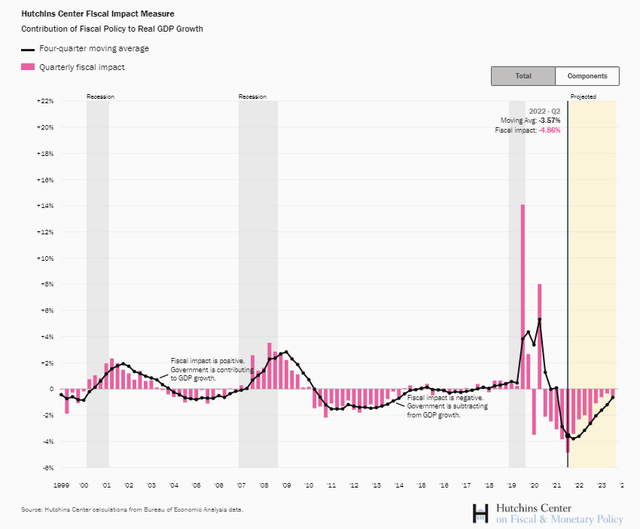

However, fiscal stimulus has rapidly changed into fiscal drag from Q2/21 onwards and will continue for another 6 quarters at present course (Hutchins):

Hutchins Center Fiscal Impact Measurement

Fiscal drag has increased notably:

In the United States in the third quarter, the so-called “fiscal drag” will slow the economy by more than 3.4 percent of gross domestic product, according to an analysis by the Brookings Institution.

And from Hutchins:

Fiscal policy reduced U.S. GDP growth by 4.9 percentage points at an annual rate in the second quarter of 2022, the Hutchins Center Fiscal Impact Measure (FIM) shows. The FIM translates changes in taxes and spending at federal, state, and local levels into changes in aggregate demand, illustrating the effect of fiscal policy on real GDP growth. GDP fell at an annual rate of 0.6% in the second quarter, according to the government’s latest estimate.

A fiscal drag of 4.9% and 3.4% in Q2 and Q3/22 really is very substantial. Not as substantial as the two stimulus packages, but these produced only a couple of quarters of impact, while the subsequent drag is much more prolonged.

And monetary policy also quickly reversed on all fronts. The Fed is raising the Fed Funds at a record pace, and long-term bond yields have awakened from decades of slumber.

QE has given way to QT to the tune of $95B a month and a rising dollar, in combination with rising interest rates, is draining world liquidity, putting companies and whole countries at risk of a debt-deflationary spiral.

What we should also realize is that it takes time for the monetary tightening to take effect in the real economy, and the amount of tightening has been such already that policymakers should wait for the effects to hold and not get spooked by Friday’s job numbers which is a backward-looking statistic.

As we showed in our previous article (linked above here), there are plenty of signs from more up-to-date indicators that inflationary pressures are already coming down substantially. The risk of overshooting is substantial and growing given huge debt levels and the perilous state of the world economy.

Supply shocks

The pandemic inflicted problems on the supply side, whilst not exactly going unnoticed, compared to the spectacular pandemic policies these seemed much less consequential.

It is understandable people would think that, however, this is more a case of death by a thousand cuts. Here are the main mechanisms:

- Shift demand from services to goods

- Create bottlenecks in supply chains

- Reduce labor supply through early retirement, deaths, long-term covid, caregiving for orphans and sick,

- Create a housing shortage.

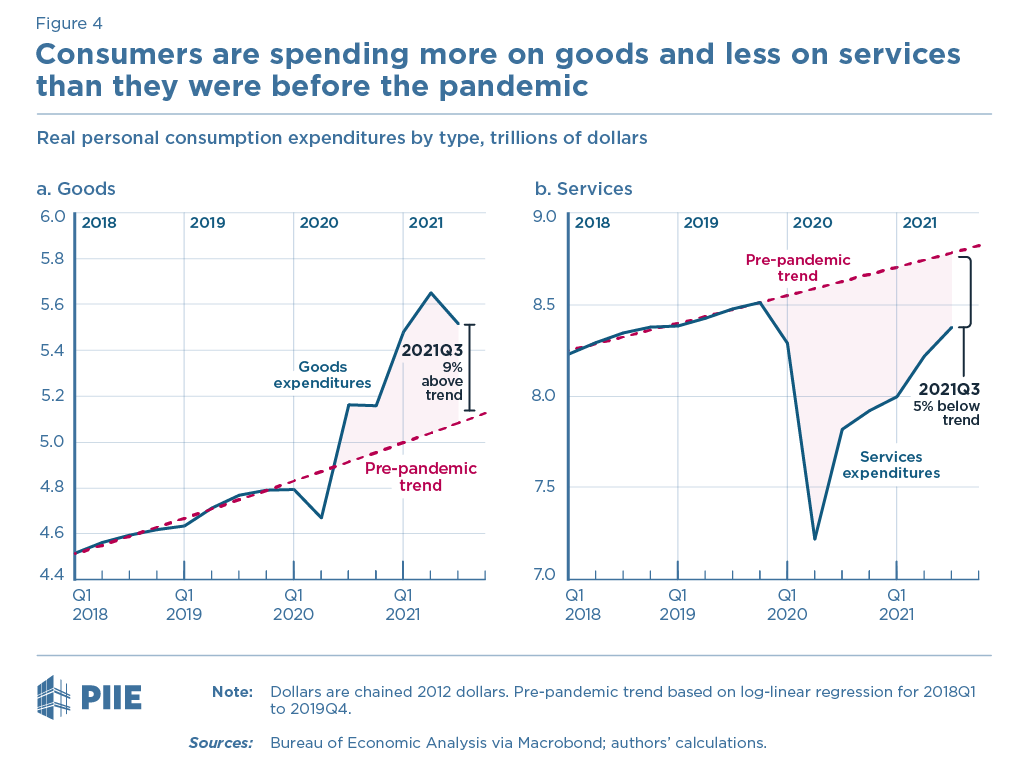

Here is how the pandemic caused demand to shift from services to goods, as many people avoided being in closed surroundings with others or were forced to do so by government measures:

PIIE

But along most of the supply chains necessary to produce these additional goods, there are also closed quarters where people come in contact with one another and even a single particular bottleneck creates ripple effects down the line.

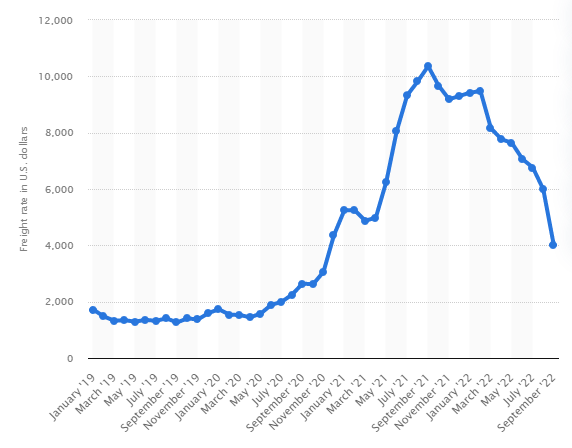

Then there is the bullwhip effect magnifying demand changes back up the supply chain, increasing the chance of bottlenecks appearing. And all that increased demand for goods had to be transported, which is where a host of other bottlenecks ensued and transport costs went through the roof. Take, for instance, container rates:

Statista

Labor supply

Labor supply took a big hit from the pandemic, which directly caused 1M+ deaths, and this is likely to be undercounted, as many were not diagnosed and excess death figures are considerably higher as people died from other causes, for instance, because of postponed medical care.

This problem wasn’t as big in the U.S. compared to some other nations but is still likely to be in the order of 15%. Of course, the majority of the people who died were no longer in the labor force but it still brought down labor supply and there are other, much bigger effects induced by the pandemic.

While there was certainly a huge increase in people voluntarily quitting their jobs (“the great resignation“), there was also a great increase in hiring so it’s not clear what the net effect of that has been.

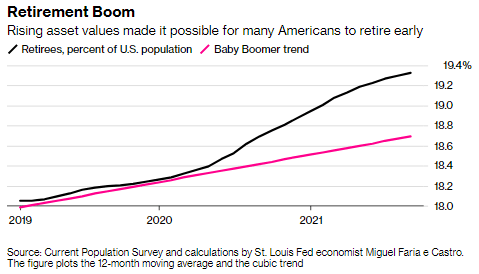

What did have a huge net effect was early retirements, which boomed during the pandemic, from Bloomberg:

More than 3 million Americans retired early because of the Covid-19 crisis, new research found. That equals to more than half of the workers still missing in the labor force from pre-pandemic levels.

Bloomberg

Long Covid might be responsible for up to a third of the reduction in labor supply, from Brookings:

- Around 16 million working-age Americans (those aged 18 to 65) have long Covid today.

- Of those, 2 to 4 million are out of work due to long Covid.

- The annual cost of those lost wages alone is around $170 billion a year (and potentially as high as $230 billion).

And there are the orphaned children (from the CDC):

From April 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021, data suggest that more than 140,000 children under age 18 in the United States lost a parent, custodial grandparent, or grandparent caregiver who provided the child’s home and basic needs, including love, security, and daily care.

They need new caregivers who might have to quit working in order to do so, add to that the care for the sick and there is another source of reduced labor supply.

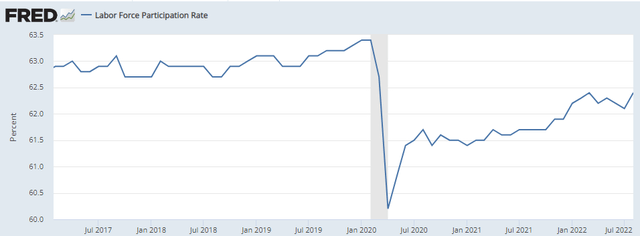

The excess deaths, accelerated pensions, people suffering from long covid and increased demand for caregivers at home all add up to a big decline in labor supply:

Labor force participation is still a full percentage point below where it was on the eve of the pandemic, which is about 1.6M people.

Housing

Another effect of the pandemic was an increase in the demand for housing, from Economic Letters:

The COVID-19 pandemic reshaped the way households work. Nearly a third of employees still worked from home part time or full time as of August 2022. This has significantly increased housing demand and is a key factor explaining why U.S. house prices grew 24% between November 2019 and November 2021.

And we previously explained how the effects linger in the CPI as there is a substantial lag, so the OER owner’s equivalent rent component which is almost 25% of the CPI (and over 30% of the core CPI) isn’t coming down while house prices are already declining.

Permanent inflation?

So inflation was mostly a supply shock, not a demand shock, and just as the pandemic problems seemed to abate the world got new supply shocks in the form of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Chinese lockdowns.

We don’t dispute that monetary tightening was necessary as the labor market was really very tight. However, so far there are few signs that inflation has become ingrained.

For that to happen either inflationary expectations have to increase a lot or a wage-price spiral has to kick into action, and there are few signs either of these is happening. For starters, wage-price spirals are very much the exception, not the rule (from the IMF):

we identified 22 situations in advanced economies over the past 50 years with conditions similar to 2021 when price inflation was rising, wage growth was positive, but real wages and the unemployment rate were flat or falling

We are far removed from the 1970s when there was a wage-price spiral in much of the western world, driven by wage indexation and much more powerful (and radical) unions.

But it does depend on inflationary expectations, so it’s important to see how these evolved, here is the New York Fed:

Median one- and three-year-ahead inflation expectations continued their steep declines in August: the one-year measure fell to 5.7% from 6.2% in July, while the three-year measure fell to 2.8% from 3.2%. The survey’s measure of disagreement across respondents (the difference between the 75th and 25th percentile of inflation expectations) increased to a new series high at the one-year horizon but decreased at the three-year horizon. Median five-year-ahead inflation expectations, which have been elicited in the monthly SCE core survey on an ad-hoc basis since the beginning of this year and were first published in July 2022, also declined to 2.0% from 2.3%. Disagreement across respondents in their five-year-ahead inflation expectations also declined in August.

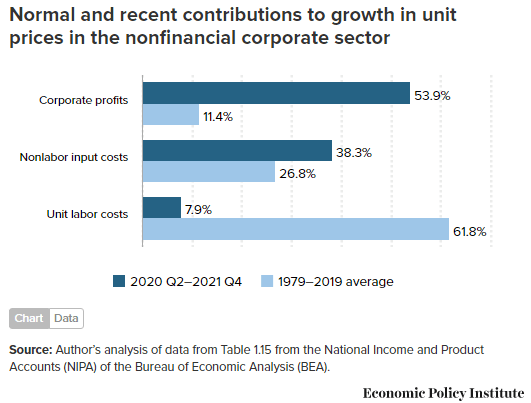

While the power shift away from labor in the past 5 decades or so has kept a wage-price spiral in check despite a super-tight labor market, there is another side to this, companies have been increasingly able to pass on higher costs. Consider the following stunning figure illustrating that power shift:

EPI

Here is the EPI:

Strikingly, over half of this increase (53.9%) can be attributed to fatter profit margins, with labor costs contributing less than 8% of this increase. This is not normal. From 1979 to 2019, profits only contributed about 11% to price growth and labor costs over 60%

That is, such has been the power shift that unit labor cost, in the past by far the biggest source of inflationary pressures have given way to corporate profits, which used to be an insignificant source of inflation.

Another sign of this power shift is that profit margins usually shrink during a tight labor market, but that hasn’t happened. That EPI study also nicely illustrates our thesis (our emphasis):

One reason to think the pandemic is the root cause of the recent inflationary surge is empirical. The inflationary shock has occurred in essentially all rich nations of the world—it’s very hard to find any country-specific policy that maps onto inflation.

Another reason is to look where this inflation started: the rapid run-up of prices in the goods sector (particularly durable goods). The pandemic directly shifted demand out of services and into goods (people quit their gym memberships and bought Pelotons, for example) just as it also caused a collapse of supply chains in durable goods (with rolling port shutdowns around the world).

While businesses in the EU tend to have less market power so it would surprise us if corporate profits had a similar contribution to inflation as in the U.S. However, there is one glaring exception: the energy markets.

Marginal cost pricing for electricity has produced a veritable windfall for electricity generators as it is only the cost of gas that has, as a consequence of the invasion of Ukraine, has gone through the roof as gas prices (which have ten-folded) are the marginal costs, marginal cost pricing (Inet economics):

means that fossil fuels still predominantly set the wholesale price of electricity, which over the past eighteen months, has risen from around £50/MWh to around £200/MWh. The result is that as the price of the marginal energy supply rises, the gains accrue to all producers regardless of their average prices… The result is a striking paradox of ‘cost inversion.’ New renewable sources, based on contracts outside the market, offer power at under a quarter of current and projected wholesale electricity prices.

Apart from producing brutal price increases leading to government actions costing tens or even hundreds of billions of euros, it also slows down the energy transition which is needed to slow climate change and become energy independent from Russia.

Demand policies for a supply problem?

We are not denying that monetary tightening should play a considerable role in bringing inflation under control. The labor market is clearly still very tight and the Fed has to prevent inflationary expectations get anchored. However, there are additional considerations here:

- Insofar as tightening money is reducing investment and house prices, it can actually add to supply constraints.

- Supply problems tend to clear by themselves as they provide opportunities for businesses.

- Given world debt levels, a moderate amount of inflation is actually beneficial.

Investor implications

We think that there is a good chance for a growing realization that inflation has been produced mainly by supply problems which are mostly one-off and there are few signs inflation is ingraining in inflationary expectations (which are coming down) and/or rising wages producing a wage-price spiral.

With the combination of inflationary pressures coming down through multiple routes (commodity prices, house prices, asset values, shipping cost, etc.) and increasing signs of strains in the world economy the risk-reward of policy will start to shift and policymakers will respond by pausing the tightening and letting the existing tightening work through the economy.

Don’t be fooled by the “whatever it takes” hardline talk of the Fed, they have to in order to restore their credibility and talk down inflationary expectations, it’s part of their job.

We think it’s likely this rhetoric will be caught by events on the ground before year-end and while we don’t see a reversal anytime soon, the tightening will likely stop. As we argued before, the only risk factor we can see is the price of oil.

Conclusion

We think that there is compelling evidence to argue that the inflationary pressures experienced in much of the world are predominantly a supply problem, caused by the disruptions of the pandemic and two years later by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Pandemic disruptions were especially large in labor markets, housing, logistics, and most services, shifting demand to goods.

Since inflation is basically a universal problem, there isn’t one policy that can be identified as its cause and while there were huge pandemic support policies, these were one-offs and are already in steep reversal.

Supply problems will mostly sort themselves out, inflationary pressures are already coming back and there is little evidence for a wage-price spiral or escalating inflationary expectations.

Given this background, the risk of overshooting on the monetary side is substantial, especially given the precarious state of much of the world economy and huge debt levels.

Be the first to comment