CreativaImages

Let us get this in first, We’re not proponents of MMT, that is, modern monetary theory, simply because we don’t see any need for it. In our view, we don’t need MMT framework in order to explain the effects of large fiscal policy initiatives.

But we were surprised when we came across Lance Roberts article titled MMT Policy Was Tried, And It Failed. We’ll argue that it was indeed tried, and produced a tremendous bang for the buck.

First things first, what is MMT? Well, Roberts provides a succinct description from Investopedia:

The central idea of MMT is that governments with a fiat currency system under their control can and should print (or create with a few keystrokes in today’s digital age) as much money as they need to spend because they cannot go broke or be insolvent unless a political decision to do so is taken.

Some say such spending would be fiscally irresponsible, as the debt would balloon and inflation would skyrocket. But according to MMT:

- Large government debt isn’t the precursor to a collapse that we believe it is;

- Countries like the U.S. can sustain much more significant deficits without cause for concern; and

- A small deficit or surplus can be extremely harmful and cause a recession since deficit spending is what builds people’s savings.

According to MMT, the only limit that the government has when it comes to spending is the availability of real resources, like workers, construction supplies, etc. When government spending is too great with respect to the resources available, inflation can surge if decision-makers are not careful.

Taxes create an ongoing demand for currency and are a tool to take money out of an economy that is getting overheated, says MMT. This goes against the conventional idea that taxes are primarily meant to provide the government with money to spend to build infrastructure, fund social welfare programs, etc.

Now, Roberts argues that there was $5T in spending, and all it produced was inflation. First off, taking the increase in the deficit as the yardstick is extremely suspect, this goes automatically higher if the economy shrinks, which it did.

But we can argue about details or figures, what we can’t argue is that there were indeed two large Federal pandemic stimulus programs, one from the outgoing government and another one from the incoming government.

What we also can’t argue is that there was, and still is a lot of inflation and that most wages can’t keep up with that, which Roberts argue as a failure of MMT. However, what we will argue:

- Rather than failure, the results show its dramatic power

- MMT was tried at the wrong time

The wrong time

Often overlooked in debates is the fact that there is a right time and place for policies and also a wrong time and place. To embark on a huge MMT experiment in the face of nasty, pandemic-induced supply chain problems is less than ideal.

The inflation that followed was at least in part the result of these supply constraints, a result of the pandemic. They are not necessarily a sign of a defect in the MMT framework.

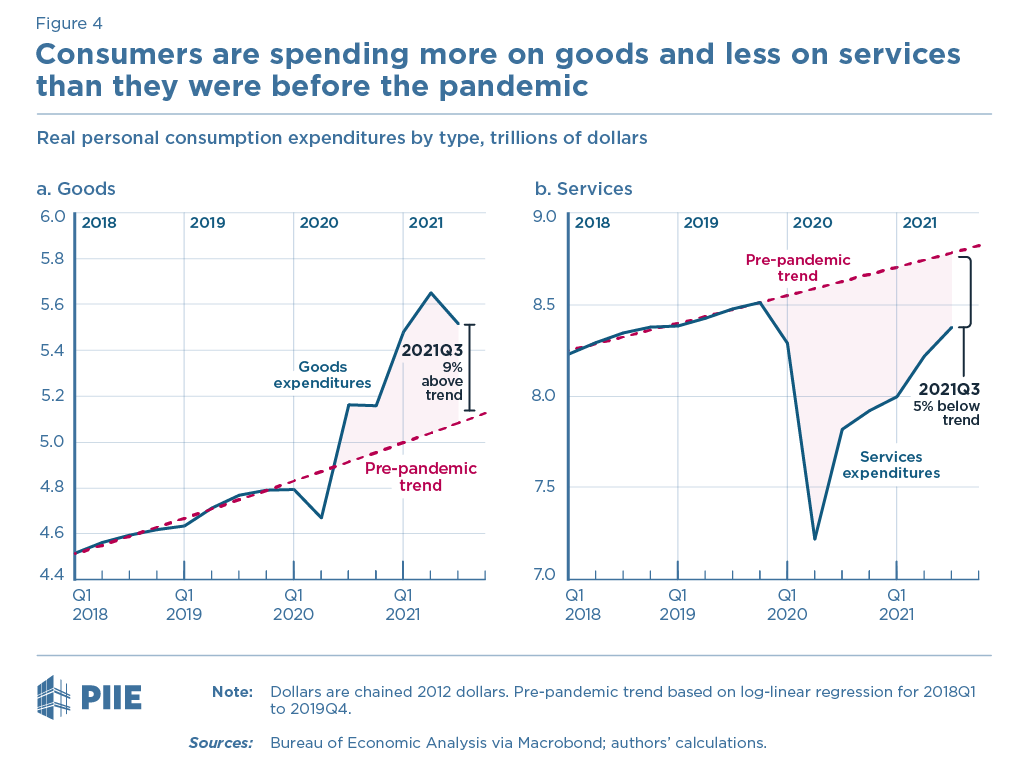

Here are two of the supply constraints, first the switch from services to goods during the pandemic, producing bottlenecks in supply chains (which services don’t have):

PIIE

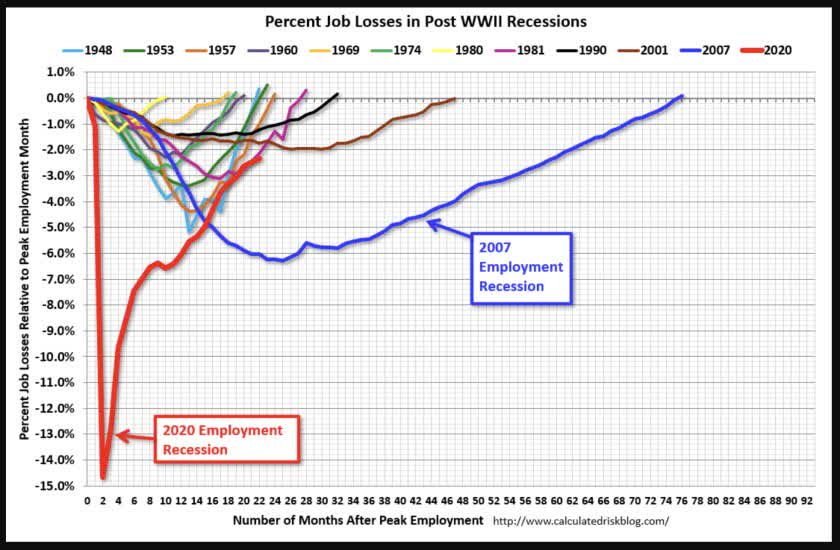

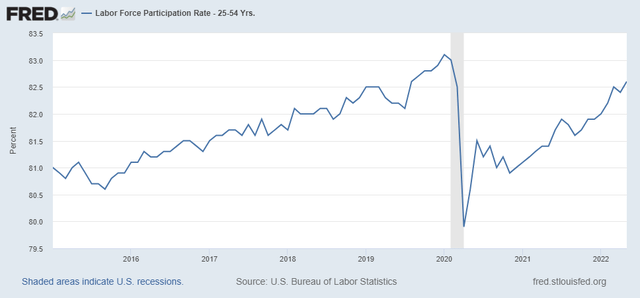

And here is another bottleneck, at least as important, labor supply:

Dramatic power

Even if one abstracts from these pandemic-induced supply problems, and blames most or even all of the subsequent inflation on the MMT-like pandemic stimulus, it could simply have been too big. Look at the figure below and tell us again that the pandemic stimulus wasn’t a success:

LA Times

That’s a sign of extraordinary force, and something we have long argued, as it happens. We have two arguments:

- In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the US (and many other developed nations) got their policy mix wrong for most of the 2010s.

- One country did do better, and the results are pretty obvious.

The austerity decade

The policy mix for most of the 2010s in the US (and other advanced countries) was to rely far too heavily on expansionary monetary policies (zero or even negative interest rates, multiple rounds of QE) whilst embarking on austerity in fiscal policy.

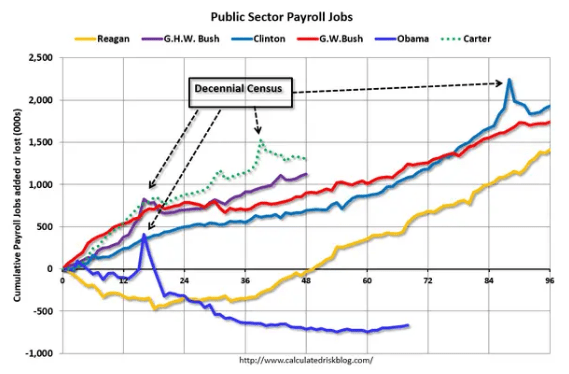

It’s not widely known that unlike the aftermath of any other economic crisis, the aftermath of the 2008/9 financial crisis saw government employment actually go down after the recession ended:

Calculated Risk

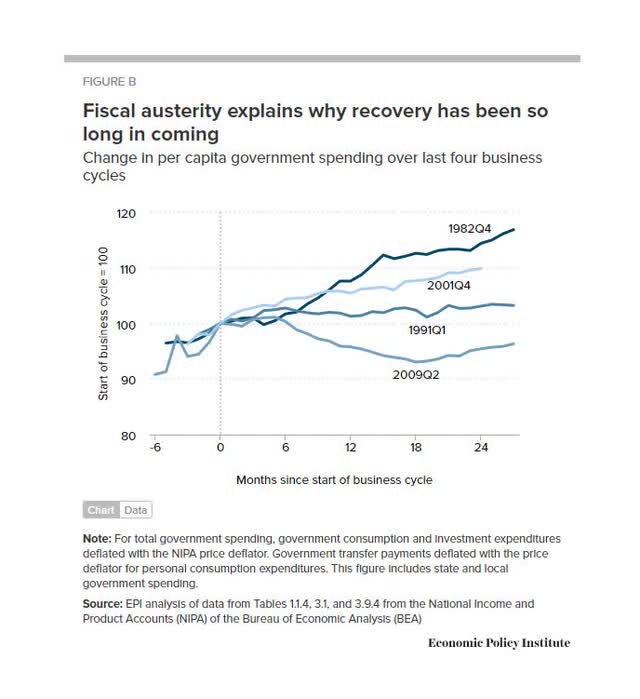

After almost 70 months, public sector employment still hadn’t recovered. And, not surprisingly, government spending was a lot less in the wake of the financial crisis compared to what happened subsequently to other economic downturns:

The reason for the austerity was that people were scared of deficits and debts, turning into Greece. But it’s very hard for a country borrowing in its own currency to turn into Greece (which was borrowing in euro, a currency over which it has no control).

Greece itself is very instructive here. It was put under troika (ECB, IMF, EU) constraints which forced extreme austerity in exchange for bailouts. This was self-defeating as the economy shrank by 25% and the debt/GDP ratio kept increasing (the “denominator effect”).

The IMF, belatedly, acknowledged the mistake (Economistview):

It is not shameful to change opinion. Rather the contrary, it is a sign of intellectual courage. Two years ago, the IMF famously surprised commentators worldwide with a rather substantial U-turn on the impact of austerity. Revised calculations on the size of multipliers led them to acknowledge that they had underestimated the impact of austerity on economic activity.

Even at that time it started with a technical paper. But significantly, that paper was coauthored by Olivier Blanchard, IMF Chief Economist. It then served as the basis for a progress report on Greece, in June 2013, that de facto disavowed the first bailout program arguing that austerity had proven to be self-defeating.

Simple Keynesian economics has long shown that when interest rates get very low, monetary policy becomes powerless (the proverbial pushing on a string) while fiscal policy becomes very powerful. This should have been no mystery and even half dimwits like ourselves argued this at the time.

A little thought experiment

Here is a little thought experiment. What if we would have spent a fraction (less than 10%) of all the QE of the 2010s on public investment, building serious infrastructure, energy transition, or any combination of whatever Mazzucata moonshots? Here is Lowrey:

We could have made investments that would have benefited all of us. And we wasted that chance. This period of unusually low interest rates, which lasted from the 2008 global financial crisis until now, was horrible in many ways. Too many people were unemployed for too long, and too many found themselves trapped in dead-end, no-security jobs while the cost of living climbed to astronomical levels. But it was an opportunity too. Borrowing was cheap, and the government could have built and built and built without crowding out private investment or overheating the economy.

We know that public sector investments tend to generate large returns (from the EPI):

Investments in public capital have significant positive impacts on private-sector productivity, with estimated rates of return ranging from 15 percent to upwards of 45 percent. (Our preferred estimate is 30 percent, which coincidentally is roughly equivalent to the rate of return on investment in information and communications technology.)

One could argue that we’re taking a what-if approach, an alternative history that is difficult to prove. However, here is the thing. There was a country that embarked on massive public investment in the aftermath of the 2008/9 financial crisis, which hit the country’s export sector very hard: China.

They really built serious infrastructure on a nearly unimaginable scale; airports, subway lines, a huge high-speed train rail network, whole cities from scratch, the works.

While some of that money was undoubtedly wasted, at least they’ve got something to show for the post-financial crisis stimulus. What do we have to show from a decade of QE, besides bloated asset prices that are now deflating?

One could also argue that inflation might have taken off much sooner if we tried MMT in the 2010s. Perhaps, it would depend on the size of the spending. What we do know is that in 2018, a $2T tax cut was passed which didn’t cause much of a start of an inflationary cycle.

While the tax cut didn’t really give much bang for the buck, (much of it went to share buybacks, it didn’t raise investment), what it did prove was that there was still plenty of slack in the economy even that late in the business cycle.

So there would have been room for public investment, especially earlier in the cycle, with little chance that inflation would take off. Real interest rates were negative, money was basically free.

A lot of structural problems could have been fixed, but we let that chance fly by, worried that QE would produce hyperinflation (per a 2010 open letter to the Fed) and the US would become Greece if it didn’t get a grip on its public deficits and debts.

In the 2010s, these were phantom worries with no basis in fact, but in the 2020s, the circumstances have changed and we no longer live in times when money is free.

Wages

I’m not sure where Roberts got the idea that MMT-ers argue that increasing government spending reduces inequality, but we don’t recognize it as a core tenet of MMT.

If there is an argument it would be based on public investment raising productivity, which in pre-1980s times would have led to wage increases, but these are slow processes and two years is way too short to assess that mechanism.

What we do know is that the pandemic stimulus got a lot of people through the pandemic and in their houses, and kept a lot of small businesses afloat so the absence of that could very well have produced a worse outcome.

Conclusion

Economic ideas and policies don’t necessarily have universal applicability. The time was the 2010s when there was a lot of slack in the economy and interest rates were close to zero.

Money was essentially free during that decade, and we could have used it to fix a host of structural problems in the US economy, more or less along MMT times.

We chose to focus on the wrong problems, we were never going to turn into Greece and massive rounds of QE didn’t set off any inflationary cycle but didn’t achieve much besides rising asset prices either. Just as Keynesian theory predicts.

So we don’t really see a need for MMT as we think a simple Keynesian framework has plenty of explanatory power to deal with the timing and size of public spending efforts.

That theory also predicts that when the slack in the economy disappears (like at present, through whatever combination of supply problems and excess demand) and interest rates rise, money is no longer free and the MMT-type policies risk unleashing inflation, especially when they are oversized.

Be the first to comment