Dikuch/iStock via Getty Images

Oil Market

I think the key point is we are not losing 5M barrels per day of Russian oil exports, because the forecast was for a global surplus (IEA, OPEC, EIA), so the amount needed to be produced outside Russia for supply and demand to remain in balance is much less than the lost 5M barrels per day of Russian exports. I think the reason prices skyrocketed like this is because the incentive to delay restocking based on the expectations of lower future prices creating a feedback loop between declining near-term inventories and backwardation of the futures curve.

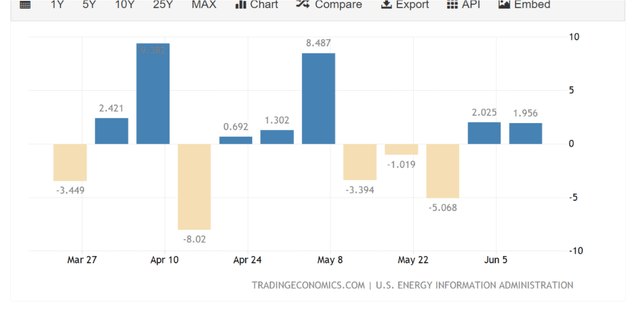

I don’t think there is a global production capacity shortage right now at all. The 1Y EIA inventory change chart is shown below. Notice it isn’t entirely one-sided draws.

US Oil Inventory Change (tradingeconomics.com)

The historically low inventories are mainly an unwillingness to pump because the futures curve continues to show future oil prices lower at longer dated contracts known as backwardation which is the opposite of contango.

I think the smart move for a US shale executive is to hedge in my opinion locking in prices above $100 a barrel and ramping production. There is plenty of OPEC capacity also especially amongst UAE, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi and the middle eastern countries. I think global demand will not hold up right as inventories are restocked. I believe in a restocking environment at low prices which causes inventory builds and pushes prices lower right as concerns about global demand become significant.

One of the problems for oil short sellers is and partially why oil prices are actually so high is producers don’t want to ramp significantly and push the market back into oversupply and therefore have been holding back. At this price level though I would expect increased production especially from shale as rig counts have been steadily rising in fact.

Inventories are around decade lows. As those are rebuilt and severe short run scarcity fears are alleviated, by OPEC+ ramping, US shale and rest of world non-OPEC and non-Russian supply, as well as potentially Iran/Venezuela and large SPR releases globally, I would think oil prices come back down from the stratosphere. Remember there is no OPEC of US shale (meaning coordination among the US shale industry) right now and there is a huge profit incentive to hedge and pump.

I’ve written extensively on contango oil trades in many articles. Contango trades profit from storing oil by locking into two contracts on a futures curve and earning the spread (profit if the curve slopes upward) by holding oil. Contango can occur in rising prices environments or falling. It is a matter of whether the market expects prices in the future to be higher.

I feel the back end of the WTI curve is the value play compared to the expensive front end if you want to be long oil. When prices at these different future dates converge or invert (i.e., oil for near term delivery becomes less expensive than oil for delivery in 6 months) it encourages restocking as all potential negative carry price downside can be hedged and profited from by a locking into a higher future selling price and just storing the physical oil. Large oil trading companies do this when the curve allows it, that is, as long as prices along the curve slope upward.

A contango restocking environment typically moves prices lower thereby self-reinforcing the cycle the other way as inventories fill back up creating a significant oversupply of oil for near term delivery and lower prices compared to the longer dated contracts. It’s a much more nuanced situation than many believe which is why I feel the oil rally is in the 9th inning at this point. If commodities come down, I think this will push US inflation down just through lower input prices but also will put pressure on emerging market commodity currencies and economies such as Brazil and Russia. US demand, growth and employment should be strong as should the US dollar, which fits with a lower oil price environment.

Large oil trading companies, and refiners who are buyers of oil, are not restocking because the futures curve is signaling prices will be lower in the future (negative carry on holding oil) and also there is an inability to hedge this negative carry because longer dated oil futures prices are lower than near term or spot prices. This means buyers of oil have essentially no choice but to draw down inventories and delay restocking. When this factor changes – meaning oil for delivery in 3-12 months is a higher price than near term delivery prices (1 month or spot) it will allow restocking and higher tanker utilization.

Also, with oil prices expected to be lower in the future as the curve is signaling now, there is also the question of why restock now at a high price? Many traders and buyers of oil are deferring restocking and likely just purchasing hand to mouth or small amounts of what is only needed at the time.

What could cause or catalyze this shift into contango from backwardation?

1) Longer dated futures rise above near-term prices on the expectation of a continued or worsening shortage this year.

2) Near-term prices fall at a faster rate than the longer dated future prices.

I think this backwardation of the curve (downward sloping) will flip to contango (upward sloping) because either the discounted back-end rises at a faster pace than the expensive front-end or the front-end is more oversupplied than people believe, inventories start to rise, and near-term/spot prices fall at a faster rate than the back end of the WTI futures curve.

Once this occurs it becomes self-reinforcing in the opposite direction where restocking causes more spot/near-term supply compared to delivery at a later date and an ever-larger contango curve structure. We saw this in March 2020 where the curve blew out to super-contango in what eventually became a negative oil price environment, then subsequently blew out the opposite way into super-backwardation. Which is why feel it is a self-reinforcing cycle in either direction.

Tankers

As a result of the Russia/Ukraine conflict, tanker ton-mile demand is set to increase in my opinion and the initial reaction of the market in tanker rates to the war in Ukraine has confirmed that. Tanker rates have recently stabilized for now at a higher yet still historically low level. I think the move in tanker rates continues upwards and the initial knee-jerk reaction to the war is correct and yet to be fully realized.

Russian oil will be sent to China or Venezuela instead of Europe adding to ton-miles. While Europe will likely satisfy demand through imports from North and South America and Africa rather than Russia – also adding ton miles.

Also, an Iran nuclear deal and return to the JCPOA would require a large increase in legal tanker utilization. Iran has been exporting on illegal tankers. With compliant production, comes the need for compliant, registered tankers from legal and environmentally regulated tanker companies.

In 2020 at the peak of the pandemic and surge in tanker rates, Euronav CEO said via Freight Waves:

The other potential headwind for (tanker) equities involves the rate hangover to inevitably follow the “tanker party.” According to De Stoop, “We all know that when oil is stored, at some point it will be consumed, and when it is, demand for transportation will be reduced and oil production will be reduced.”

That is exactly what happened, and why tanker rates subsequently crashed following the pandemic boom which even rivaled pre-2008 tanker rates. Now though, inventories have been drawn down below historical norms and if the restocking frenzy in the beginning of the article takes hold, the tanker sector would be a huge beneficiary as tankers are utilized to transport along longer routes than previously and also to store oil for profit of trading companies.

Could this lead to another hangover? Potentially, but not before huge profits and a higher tanker equity share price range repricing. It would also be of less magnitude and a bit of a smoother cycle in my opinion than the very short and volatile tanker pandemic boom/bust tanker cycle.

One reason is even if I feel the global economy will slow, it will not be turned off completely, so the total inventory builds won’t be as large (though inventories are coming up off a lower base than before which is positive for tanker demand comparatively), and therefore the subsequent eventual draw phase (negative effect on tanker rates) will be less severe for tanker equities. Essentially, I believe a future bottom in tanker rates and share prices after a potential significant tanker rate run-up is at a structurally higher level than the unprofitable environment for tankers recently.

So, I think we are going up, and even any negative after-effects due to longer term inventory draws that could send tanker rates and tanker equities lower at some point would be coming down from a significantly higher starting point and unlikely to reach the rock-bottom levels we have seen.

Post-2008, there was a huge crash in tanker rates and that is the longer-term cycle which has also healed. In the very high-rate tanker sector profit boom days prior to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, tanker owners ordered a very large number of new builds ships. When the global economy weakened oil demand fell off, while the newbuilds continued to arrive and this led to an oversupply of ships. The orderbook for new oil tankers looks much better now and building capacity is largely taken up by container ships and dry bulk vessels. The fleet is old and continues to be scrapped, especially ships which are close to 20 years old and have not been outfitted with expensive environmentally friendly scrubber technology. These are prime for scrap, which would lower supply. We are absolutely not seeing the same potential tanker oversupply issues that we have seen with the industry in the past.

Macro Backdrop

I think the US CPI will prove more responsive and potentially easier to bring to target price stability without derailing GDP growth in the United States compared to other global economies. I remain steadfast with a long US dollar theme running through the portfolio. The USD is supported by a multitude of factors. These include a significant $13T figure of global USD denominated debt, relative economic strength, fundamentals, resilience, and performance of US data versus nearly every other economy in the world leading to divergent monetary policies (where another central bank lowers or holds rates while the Fed tightens policy and sends yields higher). This creates comparatively higher real yields and strengthens a currency (the USD). Intuitively this makes sense as investors want to hold a low inflation currency that can earn a risk-free lending yield higher than other sovereign bond markets in what is called a carry trade.

In one of my previous articles, I explained carry trades. I said:

Carry trades are one of the most significant forces in foreign exchange markets. An example is borrowing yen at around 0% yield and investing in Russian bonds yielding around 7%, capturing the difference and also standing to gain on any appreciation in the RUB against the yen. It can be a profitable strategy especially when using leverage, but carry trades collapse when the funding currency (lower yielding) appreciates against the asset currency (higher yielding). This FX appreciation of the funding currency against the asset currency wipes out gains on the interest rate differential when converted back.

Japan:

According to Reuters:

Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda said on Monday the central bank’s top priority was to support the economy, stressing an unwavering commitment to maintaining “powerful” monetary stimulus.

Unlike its U.S. and European counterparts, the BOJ does not face a trade-off between the need to tame inflation and support the economy, as Japan’s inflation remains modest and driven by temporary factors such as rising raw material costs, Kuroda said.

“Japan is absolutely not in a situation that warrants monetary tightening, as the economy is still in the midst of recovering from the pandemic’s impact,” Kuroda said in a speech

In an event organized by Kyodo News, Bank of Japan chair, Kuroda, also commented on the effects of yen depreciation and said:

It is highly likely that stable moves toward yen weakness, not rapid moves, are positive for the Japanese economy as a whole. What is important for the economy is that companies that have reaped the benefits (export competitiveness) of yen weakness and seen their profits recover will increase capital spending and raise wages, and there will be a stronger cycle in the economy for more income and spending.

This makes sense and I agree with Kuroda here. The emphasis is he believes the inflation in Japan while still low is almost purely driven by cost-push pressures, not demand pull. Japan inflation has continuously lagged and undershot the central bank’s target rate for years. At a 2.1% core rate and 2.5% year/year headline rate it is far below Europe, the US and most emerging markets.

Kuroda made clear he is not about to tighten. In fact, I think a sustained period of yen depreciation is exactly what he’s been waiting for in order to sustainably move Japanese inflation and expectations higher and he’s not about to pour cold water on the escape route from Japan multi-decade zero lower interest rate bound, and secular stagnation problem.

Europe:

The hawks and doves within the ECB have been debating and ECB chair Lagarde has gone on board with the hawks, for now. According to former ECB chief economist who is very well respected said via Bloomberg:

What really annoys me in the communication first is that Christine Lagarde deviated from what she said a few weeks ago

In it, she committed to a less aggressive path of rate hikes than the one the ECB laid out on Thursday and said there was a lack of excess demand in the euro area. The latest ECB action contradicts that supposition, he said. If you use interest rates to compress demand, I think it was not really clear what she was trying to achieve by this sequence of interest-rate hikes and what sort of excess demand you’re dealing with… If you want to be a hawk, then you have to be consistent and say what you want to achieve.

I agree with Praet here – the ECB’s communication and flip-flopping has been a mess. A policy mistake is signaled by the need to reverse course shortly after and I feel the ECB with their hawkish shift and plan to moving into positive rates will be quickly unwound and reversed as the effects of Fed tightening are felt.

It is also interesting the euro has not really caught a bid with the hawkish shift meaning the FX market is either 1) doubting that tightening will actually occur or 2) thinks it will be reversed shortly after or 3) will lead to stagflation in Europe and a weak currency.

Excess demand is not the problem for Europe’s economy. It is again a cost push rather than demand pull issue and commodity price driven inflation and much more of a headline CPI problem rather than core CPI in Europe as the latter remains relatively subdued.

In my opinion, by the ECB slowing Eurozone aggregate demand and nominal growth and allowing higher yields and raising rates it will only serve to cool nominal GDP and have little effect on inflation leading to negative real growth in Europe (stagflation).

My opinion is the ECB should let the Fed do the heavy lifting with rates and global inflation and have a strong dollar. There is no sense in trying to slow aggregate demand in Europe with higher rates as it is being largely driven by food and energy prices as a result of proximity of and dependence on Russian exports. Commodities would respond more greatly downward to a strong dollar/weak euro than trying to raise rates and cool off not great already aggregate demand into a global downturn and weaker Eurozone economy.

What would be more effective in bringing down Euro area CPI without risking the economic recovery and nominal growth is to diverge from the Fed, keep rates low and let the euro fall below parity. It would push up import price inflation for Europe though energy and commodity prices would fall likely fall on an extremely strong dollar and weak emerging market demand, and a weaker euro would provide a boost to exports which the German economy among other Eurozone countries are heavily dependent on and low rates would be maintained. So overall I think that is the best move as it keeps nominal growth on track. I can’t promise the ECB won’t make a mistake here, but I feel confident I know what they should do which is continued low rates. Remember Euro area core (ex food/energy) CPI is around 3.8% compared to 6.0% in USA so there is much less of an economic overheating problem in Europe.

China:

China faces a different problem than most emerging markets in the sense it is very much “the Japan” of emerging markets with slowing nominal growth and much lower inflation than other EM economies.

China’s economy I think will be very much the epicenter of a global downturn given its size and global importance. I think the yuan will come under significant pressure as Chinese banks will need to be recapitalized by the PBOC printing RMB due to a corporate and local government non-performing loan problem for the major banks in China. The housing market has weakened and I still feel the Chinese economy has not yet bottomed out meaning lower rates will be required for China to avoid recession, let alone reach its growth target. I previously wrote:

I believe as China’s near-term economic descent continues and defaults/NPLs as well as unemployment rise, Chinese banks will become the problem. Chinese banks have extended large amounts of credit and are very leveraged. The banking system is around 200% the size of the economy compared to around 65% for the USA. This China hard landing will require lower rates and likely printing of RMB by the PBOC to recapitalize banks for bad loans in order to navigate through it while awaiting a consumer rebalancing. One of the main issues will be preventing unemployment from rising thereby stymieing the Chinese consumer demand rebalancing away from the supply-side driven construction model. China will likely have to rely on strong exports to the rest of world, to keep their labor markets operating at a good level

If Chinese rates are lowered further and expected to stay low, the yuan could become a popular funding currency for carry trades meaning it is borrowed at a low Chinese sovereign yield, converted into a higher yielding currency such as the USD or BRL (as US Treasury yields have now surpassed Chinese 10Y bond yields and Brazil yields are north of 10%). The trade gains on appreciation in the USD or BRL against the yuan as well as the interest rate differential. This would lead to downward pressure on the yuan against the USD or BRL when done in mass, as a couple examples.

Petrobras

Petrobras (NYSE:PBR) trades at a discount and has a higher dividend yield than other oil majors, yet there are reasons markets have assigned this discount and that is because it involves increased risk. Petrobras is foremost a Brazilian company though also trades in the USA under an ADR and there are different risks such potentially lower emerging market equity valuations as well as currency risk affecting a company’s debt service capability when investing in foreign markets.

Unlike China, inflation rates are typically high in emerging markets and EM currency depreciation in foreign exchange markets is associated with this relatively higher emerging market inflation rate. A weak currency increases import cost pressures which current account deficit economies (net importers) are most affected by. So, to defend the currency and prevent capital outflows a given emerging market central bank would raise rates in order to protect their relative yield advantage from other central banks such as the Fed tightening and moving their economy’s yields higher. This disincentivizes selling pressure in the currency due to it being higher yielding, lowers import costs and cools demand in the economy all exerting downward pressure on inflation. The problem is the trade-off between nominal growth and employment against inflation or the question could be posed as how much pain a central bank is willing to endure on GDP growth, asset prices and employment in order to keep the CPI in check and exchange rate stable?

For example – Brazil has moved their central bank policy rate up from around 2% to over 12% over the last couple years. The significance of the move in rates has not led to equally significant upward pressure in the Brazilian currency, the BRL. I ask, if not even a 1000 basis point move in the Brazil policy rate can ignite strength in the BRL, the path is likely downwards for the currency as high rates begin to weigh on the Brazilian economy and a pause is warranted. If the strong USD, tighter Fed policy, and a slowing China cause commodity markets to decline from very high levels currently, it would almost definitely affect Brazilian commodity exports which the Brazilian economy is very dependent on, and this would weigh on the Brazilian GDP and employment picture and factor into the central bank of Brazil’s interest rate decisions.

While Brazil’s central bank has been most extreme in their interest rate movements and gaining a relative yield advantage, it is a common theme among emerging market monetary policy with many other central banks doing the same to a lesser degree.

How does this affect Petrobras, a large Brazilian oil producing company?

First in a restocking and contango type oil market as described above, oil prices would likely move lower directly affecting revenue and profitability.

Secondly, this lower oil price environment would also occur alongside a strong US dollar. Petrobras has a significant figure of USD denominated debt, meaning a weak BRL and strong USD would affect the company’s profitability through a higher real burden of debt repayment. There is also a great degree of political interference in the company, which is subject to risks.

Petrobras has $12.25B in USD denominated debt due before 2030 along with other debt. I am only focusing on the shorter-term USD-denominated figure. Suppose the BRL currency depreciates 10% against the USD over the short-intermediate term. This adds over $1.2B in real debt expense to the first figure.

Petrobras has a cash and short-term investment balance of 745B BRL or $14 billion when converted at the current exchange rate of around 5.21 USD per BRL. It has a total current asset position of 154B BRL or around $29.5B USD. Current liabilities such as accounts payable and short-term debt is around 124.5B BRL or $23.89B USD.

The current liquidity or current asset to current liability ratio is around 1.24 though if the BRL were to come under more severe pressure while oil prices fall, the ratio could fall below 1.00 and liquidity could come into question and the large dividend being paid to Petrobras investors could be reduced or cut. Fitch and S&P rate Petrobras’ debt at BB- while Moody’s rates it at Ba1 which all place in high-yield or riskier territory.

DHT

DHT (NYSE:DHT) owns entirely VLCC tanker ships also known as very large crude carriers, and I think that is the main draw to investing in DHT versus other tanker companies right now. According to the latest DHT conference call:

To the sanctions and ensuing trades trade disruptions coming out to the rest of the Ukraine conflict seems to be increasing transportation distances. So far, most visible to ships smaller than VLCCs. If freight differentials become too wide, freight tend to flow up and down between the different ship sizes. We saw some of this at the outset of the conflict and should regulate trades see these differentials come back the theory that the tide lifts all boats to hold true.

The pop in freight rates for VLCCs that you saw a few weeks back is a good indicator that underlying balance is not as bad as the current rates are indicating. Keep in mind that VLCCs typically transport almost 45% of all seaborne crude oil volumes, that closer to 60% on a ton mile basis. This is truly the workhorse of the oil industry.

The trade disruptions are changing sourcing of refined oil products, elevating freight rates for product tankers. As this happens at a time of low inventories of both crude oil and refined products, it backs the question whether product tankers are front running crude tankers suggesting the amount for feedstock and thus crude oil transportation to come next.

Much of the focus of the latest tanker earnings call transcripts is about the effect of Russian sanctions on ton-mile demand (distance) as well as vessel supply. Little is mentioned about the continued drawdown in crude inventories besides from Scorpio Tankers’ Lauro who said, “supplying incremental oil demand with inventory draws is not sustainable in the long run”.

Not only is DHT’s tanker class specialization poised to benefit in my view from increased global transportation due to re-routing of Russian oil and restocking of oil, as the industry “workhorse”. VLCC’s are also the most used to store oil in contango trades where large oil trading companies lock into selling oil at a future date at a high price and gain the futures curve differential throughs storing the physical oil. Again, this can only happen when the futures curve slopes upward which is what I am expecting.

I also want to make the point we are seeing divergences among vessel sizes and carrier types with spikes occurring in smaller sized aframaxes as well as refined product tankers. Product tankers which carry refined oil products and smaller sized aframaxes have outperformed very large crude carriers.

DHT and the VLCC tanker class rates have underperformed other tanker companies and vessel classes making it a value play among the already cheap tanker sector.

For example, Scorpio Tankers, which is a product tanker company is up around 200% YTD, Teekay Tankers which owns mostly smaller vessels is up around 54% TYD, with DHT only up 18% as a pure-play VLCC class investment.

DHT has a current asset to current asset to liability ratio of 2.86. This makes it less risky from a debt service perspective than Petrobras where the current ratio is 1.24 as stated in the above section. Tankers are also more versatile being able to perform in bullish and bearish oil price scenarios while also providing plenty more upside firepower than higher priced energy producers in my opinion.

Valuations for tanker equities and tanker rates are still historically very low. DHT has a market capitalization of $1.07B and over the last 5 year has generated revenue at an average of around $450M annually. For comparison, the same statistic for Apple is an average 5Y annual revenue of around $280B yet Apple’s market cap is approximately 8 times the 5Y average annual revenue compared to around just 2.3X for DHT. Petrobras’ market cap to 5-year average annual revenue ratio is also in the high single digits meaning an investor is paying significantly more for revenue earned by Petrobras compared to DHT.

Conclusion

At some point the expectation of a worsening oil shortage could cause increased oil purchasing and tanker demand as buyers rush in to compete for limited oil supply. This would involve strong global growth and energy demand as well as transportation of oil to the benefit of tanker companies.

Or the alleviation of oil scarcity worries due to inventory builds (SPR releases, OPEC ramp, US shale rising rig counts, increased global supply with weak China and emerging market demand) will cause the futures curve to shift to a contango setting – meaning prices for later delivery are higher than spot or near-term delivery prices. Once this occurs, oil would be transported in mass back into tanks around the world leading to very high utilization of tanker ships. Again, this higher utilization of tankers either from satisfying global demand or restocking of oil can occur in two scenarios (bullish oil prices OR bearish oil prices).

The reason a contango curve structure – meaning higher expected future prices than near-term or spot prices allows restocking is – an oil refiner or trader can lock into selling oil at a specified price at a specified date. If the futures curve allows this specified price at a future date to be higher than the current price, the trader or refiner can restock now. As it stands currently, they cannot, due to a downward sloping futures curve meaning prices are expected to be lower in 1, 3, 6 or 12 months from now.

With prices expected by the futures market to be lower in several months, it begs the question, why restock now especially if one cannot hedge into a higher selling price? And that is precisely why you have seen huge oil inventory draws over 2021 and into 2022 and contributed greatly to continued high prices. I am quite honestly surprised the draw phase has been so prolonged, as eventually even those bullish oil will have to look to the discounted back end of the WTI futures price curve as a deep value play which would narrow the backwardation as buying longer-dated futures pushes up the back-end relative to the near-term delivery or front-end.

Lastly regarding sanctions not relating to Russia, but to Iran and Venezuela, if either are relaxed or lifted (and there have been positive developments on Venezuela, less so recently with Iran), it would involve increased scrapping of older and non-compliant or illegal tonnage/ships as well as more supply to be transported via regulated and legal vessels such as those owned by major tanker companies.

In conclusion, I rate Petrobras a sell and DHT a strong buy.

Be the first to comment