Bruce Bennett

This article was coproduced with Christopher Volk.

On November 8, concurrent with a rare lunar eclipse, Kohl’s Corporation’s (NYSE:KSS) CEO Michelle Gass announced she would be stepping down as Chief Executive Officer after four years, electing to accept a senior leadership position with Levi Strauss. Both she and Kohl’s have been under withering pressure from analysts and activist investors to boost the company’s beleaguered share price.

This event raises an obvious question: What’s the new CEO to do differently?

A Brief History

Twenty years ago, Kohl’s was primarily a potent regional retailer, operating just over 450 locations from its perch in Menomonee Falls, Minnesota just outside Milwaukee.

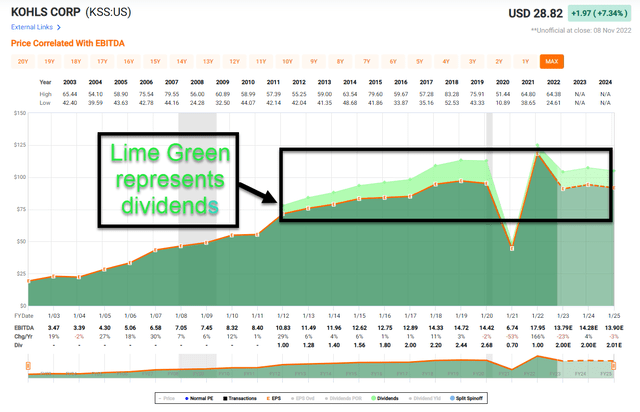

Every year, the company could be counted on to grow its store count by nearly 20% as it set out to expand nationwide, which drove earnings growth that unsurprisingly averaged about 20% between 2002 and 2007.

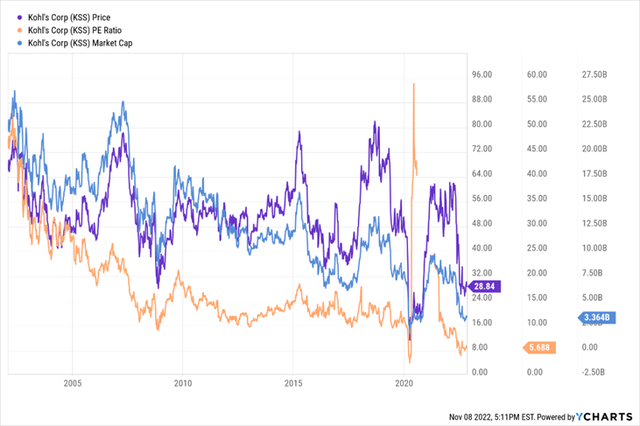

Given this pace of growth, the company’s P/E ratio stood at around 46X at the end of January 2002, delivering an equity market capitalization of more than $22 billion. The company’s all-time high Price/Earnings multiple stood more than 70X about a year prior.

Kohl’s Equity Capitalization, Price and P/E Ratio

All multi-unit retailers eventually run out of revenue growth gas. By 2009, with fewer remaining markets to penetrate, Kohl’s rate of store expansion had fallen to below 10%.

At the same time, earnings became more volatile and average earnings growth fell by half. With elevated competitive pressures, the company’s vaunted 6% net income margins demonstrated increasing volatility and likewise gradually fell by a third.

With such volatility and headwinds, the company’s price earnings multiple would unsurprisingly fall to the low teens with its equity valuation falling in half by 2010. The equity capitalization would also show volatility but remained in that zip code for the next decade.

Pulling the Financial Levers

All business leaders have three corporate efficiencies at their fingertips:

- Operating Efficiency

- Asset Efficiency

- Capital Efficiency.

Their favorite is the first, which Kohl’s ably used as it grew its sales through new store development, while maintaining an enviable level of profitability relative to other leading discount retailers.

But, as companies mature, so does leadership focus.

In 2007, the company turned to Asset Efficiency, materially lightening its balance sheet by selling off its $1.6 billion in credit card receivables.

That year, they began buying in shares, using most of that money to acquire more than $1.5 billion of stock. The share price popped nearly 60% as a result, but the rise was short-lived. You can only pull off this trick once.

With its 2007 share repurchase, Kohl’s set out on capital efficiency strategies.

Between the start of its 2007 fiscal year and the conclusion of its fiscal year ended January 31, 2022, the company would go on to buy in nearly two thirds of its stock. It would also begin to pay dividends starting in 2012, further reducing its equitization.

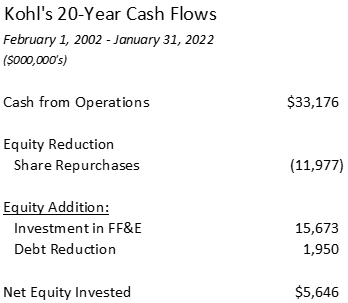

Buying in shares and paying out dividends alone do not tell the story of Kohl’s success with the capital efficiency lever. There is the important matter of free cash flow investment. Over the twenty-year period ending January 31, 2022, the company’s invested free cash flow looked like this:

Chris Volk

Over 20 years, Kohl’s bought in nearly $12 billion in shares, while investing over $17 billion of equity back into the business in the form of store expansion, other fixed asset purchases, and a net reduction in borrowings.

In the end, the company invested about $5.5 billion in net equity into the company. With a current market equity capitalization below $4 billion, it’s safe to say shareholders were not rewarded by its investment.

Kohl’s equity at cost at the start of its 2003 fiscal year approximated $13 billion, meaning that the company has cumulatively destroyed approximately 70% of every equity dollar it has ever invested.

It has been lighting shareholder money on fire.

The Anchor

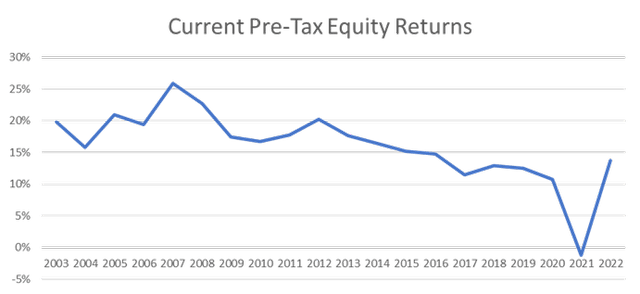

Shareholder value erosion results from business models that deliver shareholder returns that are below their requirements. The three corporate efficiencies work together to make this happen.

When it comes to Kohl’s inefficiencies, there is a singular glaring anchor: At the start of its 2023 fiscal year, the company owned 410, or 35%, of its 1,165 locations. It also owned seven of its nine distribution centers (it wisely and profitably did a sale leaseback on its California location in 2020), its corporate offices, and 6 e-commerce fulfillment centers.

In choosing this real estate ownership path, Kohl’s elected to have a conservative, highly equitized capital mix that resulted in corporate investment-grade ratings.

In September 2022, Moody’s placed the company’s Baa2 on a watch for possible downgrade. Standard and Poor’s beat them to the punch. At about the same time, they downgraded the company to BB+, or the first stop of “junk/high yield” status.

Anyone who knows me knows how I feel about high volume, low margin retailers and service companies that own material amounts of real estate. Generally speaking, high volume, low margin businesses have no business driving investment-grade ratings through the ownership of such huge amounts of real estate.

In perhaps its biggest error, Kohl’s also owns 238 buildings that are situated on ground leases. Here, they get the chance to pay rents to their ground landlords while occupying buildings that they paid for but will never ultimately own.

The seeds for Kohl’s capital inefficiency were set well before the tenure of Michelle Gass, though she did nothing to modify the company’s debt/equity mix. The company had a real estate ownership and ground lease ownership bias from its earliest days.

With the lack of lease and debt payments, rapidly expanding retailers are often lured by the more rapid earnings growth that comes from real estate ownership. And, if they are trading at high multiples, as Kohl’s had been, the immediate costs of equity can look cheaper than debt or leases.

For a time, shareholders can be caught up in the growth and oblivious to the inefficient debt equity mix and its impact on business model inefficiency. But, over time, the business model will reveal itself and shareholders can pay a steep price.

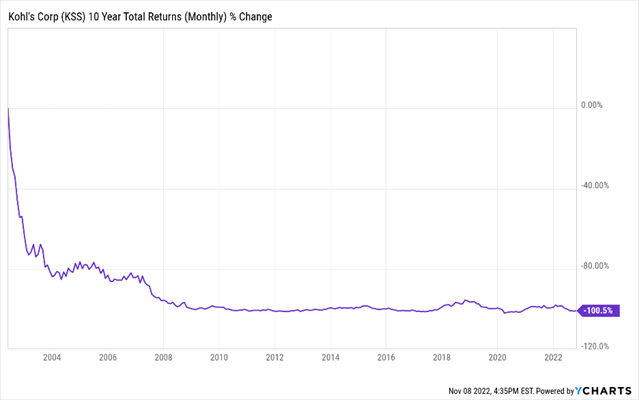

The result of all of this is that, for better than twenty years, Kohl’s has been a miserable stock to own for the long-term. Investors who have made money have done so by making calculated short-term, event-driven bets on the shares, most recently in 2021 given the company’s privatization prospects. Unsurprisingly, the privatization thesis centered foremost reversing on the company’s inefficient capitalization.

yCharts

What To Do?

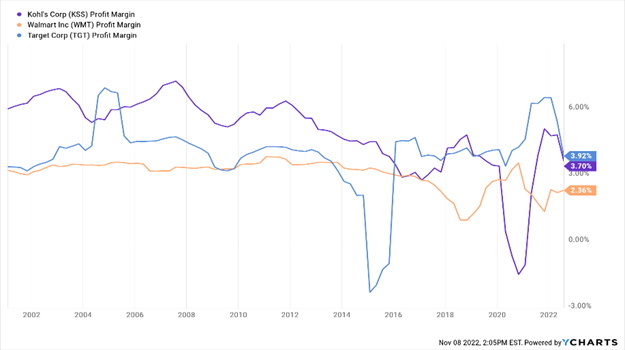

There is some good news for the future CEO of Kohl’s. While the company’s former 6% margins have given way to net income margins of 4% and less, it holds its own when compared with leading discount retailers.

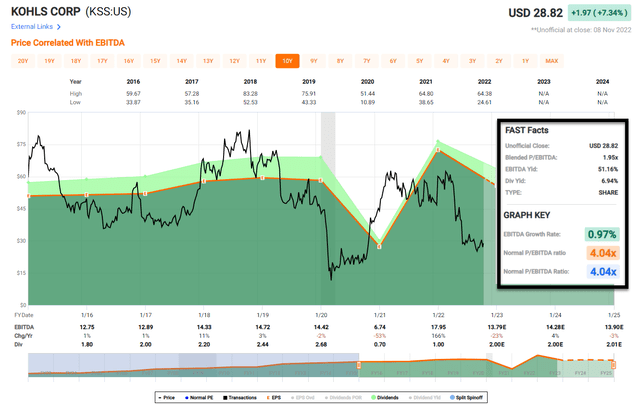

Moreover, its current pre-tax equity return, computed using the Value Equation, or V-Formula, stood at around 13% for its most recent fiscal year.

Right-sizing Kohl’s capital efficiency lever by selling much of its real estate would serve to elevate returns and hopefully recover some of the lost shareholder equity value. One impediment here will be the degree of tax leakage from asset sales.

An opportunity cost of corporate real estate ownership is that depreciation makes it commercially harder to effect real estate recapitalization strategies because of gain on sale tax costs.

The timing is also less than ideal, given higher interest rates, wider borrowing spreads, and resultant higher real estate cap rates. Nonetheless, this will eventually be something incoming leadership needs to acknowledge.

Margin improvement would also be nice, but shareholders would probably opt for a strategy to deliver greater margin consistency. Companies having greater performance consistency and reliability can improve their cost of equity and lower the cost of required current equity returns.

In the case of Kohl’s, the pandemic exacted a large cost, while giving a boost to the margins of discount retailers selling essentials. Post pandemic, the company’s margins are showing signs of life, but performance volatility is harmful to investor return requirements.

Kohl’s Net Profit Margin vs Walmart (WMT) and Target (TGT)

yCharts

Growth, which is the one element that shareholders historically rewarded Kohl’s for the most, will be likely elusive. It will hinge on the company’s ability to realize same-store real inflation-adjusted growth.

Over the past ten years, the company has built 67 stores and closed 21, averaging less than four new units annually. This net new store development within its highly penetrated markets is a meaningless number on its large base of 1,165 locations.

Less ability to reinvest free cash flows in an accretive way (and the company has historically been a poor investor of its free cash flows) suggests the need to pursue a “cash cow” strategy, offering shareholders a return path centered more on dividends.

In the end, it is this dilemma that might determine whether Kohl’s can be aptly valued as a public company.

Be the first to comment