JasonDoiy

Investment Thesis

The collapse in earnings currently is the result of reduced demand, exacerbating the reduced margin due to heavy investments, as Intel (NASDAQ:INTC) executes on its plan to regain leadership.

While on first look Intel had a relatively decent Q3 (compared to the previously reduced expectations), it could have been a lot worse if not for what seems to be a pull-in in demand ahead of Q4 PC price increases. Given that, in addition, the data center has continued to deteriorate as well (even more than the PC), as Intel’s Q4 guidance reflects (down QoQ from Q3), there could be further downside over the next year.

While the reduction in revenue is leading to an increased focus on cost savings, which may partly offset this downside financial trend, the plan to regain process leadership in 2024-2025 remains on track (and Intel indicated the layoffs won’t impact those critical areas as much). Overall, Investors who are onboard the turnaround train should continue to remain patient, although as mentioned there could be more downside in 2023 as (per Intel’s own admittance) there is no financial recovery yet in sight.

Background

I recently discussed Intel’s Q3 results from a more high-level view. The current macro-environment deteriorating has come at a very unfortunate time, as Intel is still in the deep trenches of executing on its turnaround plan, with visible results still some time off. So as spending has increased (capex, R&D) and the financials have decreased (combined with lower margin due to the 10nm ramp), Intel’s profitability has dried up.

As such, as signaled by the lay-offs as part of a new cost reduction program, I questioned Intel’s ability to (fully) fund its strategy going forward. At the very least, the reduction in earnings has made me expect further pressure on the stock in the near-term, despite the initial Q3 rally. (Note that Intel’s stock has both rallied and declined in the past, often just temporarily, based on some news item, such as the 7nm delay, Microsoft (MSFT) Arm chip efforts, or the Pat Gelsinger appointment.)

Q3 results

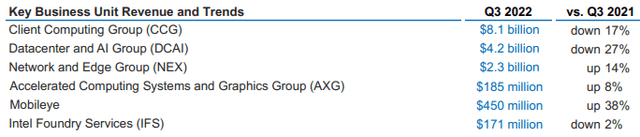

Intel’s Q3 results actually weren’t all that poor, in particular the PC results. Overall, only two of the six segments were meaningfully down.

PC

The PC results were subpar, but certainly not awful, as I only had to go back to 2018 to find a similar quarter of $7.6B platform revenue. While this is certainly a lot lower than the 2021 figures which had over $9B platform quarters, compared to the pre-pandemic figures (which are to some extent also “pre-AMD” (AMD) as well as “pre-Apple (AAPL) silicon” figures, which have added to further downside over the last few years), the Q3 results were “only” on the order of ~$1B lower.

As noted, given that AMD has gained at least some market share, and the absence of Apple Mac silicon in 2022, this isn’t too disastrous. It was actually a decent sequential uptick from Q2 – whereas AMD saw an enormous decline. Nevertheless, Intel did mention there may have been some shipments in preparation for the Q4 increases.

On the other hand, Intel is still undershipping the market due to ongoing inventory correction. In any case, the reported PC TAM that is nearly 300M units is still much higher than pre-pandemic. So for some solace, if the economy was really on the brink of a collapse, the results could have been a lot worse (as exemplified by AMD’s).

Data center

Now, here is where the real let-down happened. The analyst community has been so fixated on reporting the PC TAM (in units), that a lot less attention is going to the data center TAM. While it is known that due to various pressures (most notably AMD), Intel has been shedding a noticeable amount of share, no official server TAM is reported, so it is not possible to distinguish between demand reduction (TAM contraction) and share losses, although Intel did claim there was TAM decline.

Intel reported DCAI revenue of $4.2B, a more than $0.4B reduction from the already weak Q2 result. For comparison, to know how to judge these results, Intel’s worst quarter since the 2019 “cloud digestion” was the notoriously weak Q1 2021, which had $4.9B revenue. Note that DCAI (unlike DCG previously) also includes the FPGA business, which Intel said was up 25%, so the CPU part of DCAI must have performed even worse than the print suggests.

NEX

Network and edge was very slightly down QoQ, although still up mid teens YoY, making it a relatively strong performer.

AXG

The GPU (or blockchain) ramp is still not visible in the results, which are still dominated by licensing revenue. Intel also hasn’t updated on its 4M GPU shipment target, which it previously said it would not achieve.

In any case, aside from the Blockscale product, both the consumer and data center products have been delayed, with Ponte Vecchio slipping from H2 2022 to January 2023. In addition, Intel has now formally announced its successor, Rialto Bridge, for 2024. Intel had previously said it would start sampling in mid-2023, with Falcon Shores touted for 2024. But since sampling usually occurs around a year before products, a launch in 2024 was inevitable, so it does put some question marks around Falcon Shores, which was meant to be the next major product after Ponte Vecchio, and the competitor to Nvidia’s (NVDA) Grace Hopper CPU+GPU product.

The issue is further that both the schedule and specs make Rialto Bridge an uncompelling stopgap before Falcon Shores, with Intel targeting +30% performance, mainly from +25% cores. This suggests that Intel is not moving to N3, which is disappointing for a 2024 product. Note that this is also just three years before Intel’s zettascale target, a 500x performance over the 2023 Aurora supercomputer. Certainly a 30% improvement (at a 33% power increase) isn’t going to suffice to reach zettascale.

This hence makes Falcon Shores even more important. Intel has previously said it would leverage angstrom-level process technology, but it is not certain if this is the case for both the GPU and the CPU. Given its delay to 2025, Intel should ideally use its (self-proclaimed) 18A process leadership to deliver two process nodes of improvement over Rialto Bridge in one year.

IFS

While IFS recovered a bit from Q2, this business is basically still in the pre-revenue phase, with the important Tower acquisition not expected until Q1 next year.

Intel did disclose that the first foundry test chip (of an “important” potential customer) is now going through the fab.

Mobileye

Revenue of $450M was slightly down QoQ, although still up nicely YoY. While much fanfare was about the IPO, Intel remained very quiet about the robotaxi business, which was years ago scheduled to start in 2022. As noted previously, it is unknown if the issue is technologically or regulatory.

Overall results, guidance, gross margin and reorganization

The top-line result, overall, was within guidance. However, Intel had said in July that Q2 and Q3 would mark the bottom, but further weakness is forecasted for Q4 given the ongoing macro. In my initial Q3 preview, I noted that unless there would be a further QoQ decline (which there is), the YoY guidance was safe. This bear scenario is exactly was seems to be materializing, as Q4 will mark another bottom, and has also resulted in another guidance reduction after the already ~$10B reduction announced in July.

Since PC usually tends to be strong in Q4, Intel had been fairly bullish about some PC upside in Q4, but given the pull-in in Q3 ahead of the Q4 price increase, Intel is expecting all segments to be weak.

Moving to the bottom line, Intel reported a decent beat, which I saw on Twitter was one of the strongest beat of the tech companies that reported that week. However, the beat was entirely due to a tax benefit. The actual beat was negligible. GAAP EPS was $0.25, down 85%. Note that the Q2 non-GAAP earnings came in at $0.29 EPS, down 79%, and the Q4 outlook is also just $0.20, so this seems to be the new normal, and it is what I cautioned for in my initial Q3 discussion: margin erosion due to higher investments and lower revenue and gross margin.

This explains the $3B cost reduction program for 2023, split between $1B cost of sales and $2B operating expenses. I assume the COGS benefit will come from higher 10nm yield, leading to some gross margin improvement. This still leaves $2B in opex that needs to be reduced. For example, perhaps Intel could split this between $1B in R&D and $1B in SG&A, but anyhow it seems Intel is done with the ramp in R&D that had been visible since early 2021.

Dave Zinsner: These savings will be realized through multiple initiatives to optimize the business, including portfolio cuts, right-sizing of our support organizations, more stringent cost controls in all aspects of our spending, and improved sales and marketing efficiency

Intel hired 14k net new employees over the last year, and ~20k since the CEO transition. Despite the further increase in Q3, R&D actually decreased QoQ for the first time since early 2021. The run rate is over $17B currently, around 27% of revenue, around $4B higher than the pre-Gelsinger run rate.

For the long-term the plan is to reduce expenses by $9B at the midpoint, now split between $3B opex and $6B COGS. Intel expects this to be realized by the end of 2025. Again, I would bet Intel is targeting manufacturing efficiencies as a result of regaining process leadership in order to drive these improvements, so perhaps this $6B target is simply (at least to some extent) what Intel estimates is the benefit of executing on its IDM 2.0 strategy, and put this forward in order to appease investors. Nevertheless, the timing seems quite aggressive as by the end 2025 it is unlikely that 18A will already be fully ramped. Intel did add an asterisk to the $10B target:

Not captured in these estimates are the startup costs to support five nodes in four years, which will begin to subside beyond calendar year 2026 – adding an additional about $2 billion in cost of goods savings.

This statement is a bit baffling. While, together with another remark, some interpreted this as Intel putting its process roadmap on hold, obviously Intel will always need to incur startup costs at about a two-year cadence as long as it pursues Moore’s Law (and is able to deliver at this cadence).

In addition, as I initially missed, Intel seems to explicitly state it is going to spare the process and product development teams from the headcount reductions:

These are difficult decisions affecting our loyal Intel family, but we need to balance increased investment in areas like leadership in TD, product and capacity in Ohio and Germany with efficiency measures elsewhere as we drive to have a best-in-class structure. While this makes me a bit more bullish that this is not going to be company-wide axing of employees like in 2016-2017, the reductions of course will still have an impact somewhere.

Finally, Intel’s gross margins have been awful this year to the point of reaching Bulldozer-era AMD levels. Although the non-GAAP numbers are still somewhat up there, the GAAP one of 42.6% is some 20 points lower than when Intel still had a near-monopoly and process leadership. (There used to be a time when management was roasted by analysts about one or two points up or down.) Guidance for Q4 is another meager (non-GAAP) 45%.

For one more note about operating margin, people have noticed the 0% margin in DCAI. There are several reasons for this. While, sure, some of it (as Intel itself cited) is due to pricing pressure to stay competitive, there are three others. First, the lower gross margin from moving the portfolio to 10nm as well as the investments in the next nodes. Secondly, the heavily increased R&D investments. Thirdly, obviously the lower leverage from lower revenue.

Further discussion

Meteor Lake

In 2020, Intel had delayed Meteor Lake by around six months, to early 2023. Intel’s revised process roadmap, with Intel 4 in H2’22, supported this plan, but it currently seems that Intel has dropped this plan, staying to its usual annual cadence. Since the current generation is Raptor Lake, added as stopgap but nevertheless received quite well and holding up decently against the 5nm competition, this means Meteor Lake should launch in fall 2023.

What this effectively means is that Intel, supposedly, has the Intel 4 process node ready for manufacturing, but is not using this yet (as there are no products), with production likely ramping through 2023.

Since Intel has not revealed any yield data, following is just speculation, but one could question if the Meteor Lake delay to (what seems) late 2023 (more than Intel had initially announced) is simply coincidental, or if Intel 4 is perhaps not progressing as strong as it initially seemed in the second half of 2020. In any case, Intel said Granite Rapids on Intel 3 has a healthy yield.

Process roadmap and Arrow Lake

Officially, Intel said all of its nodes through 18A remain on schedule. Nevertheless, while Intel mentioned the 18A test chips, what might have been more compelling was an update on Arrow Lake. It may not seem like it (which is why the update could have been a strong signal), but Arrow Lake is supposed to go into production less than 18 months from now (around 12 months after Meteor Lake). Nevertheless, Intel announced the Meteor Lake tape-in in Q2’21, but well over a year later there has been no mention of its Arrow Lake successor yet.

In any case, for the long-term health of the company, arguably this process roadmap is the only thing that matters. While Intel said it is going to slow down its roadmap after 18A, I interpreted this as simply going back to a historical two-year cadence instead of the current accelerated cadence. As Pat Gelsinger has said a few times, all the nodes are lined up for the rest of the decade.

Sapphire Rapids

In the last few months, I have seen at least two rumors regarding the launch of the Sapphire Rapids Xeon. The first proposed a February-March timeline, while the second one cited low yield causing a postponement to the second half of 2023.

However, just as I was about to submit an article about how Intel was finished, Intel tweeted about a launch even for Sapphire Rapids scheduled for January 10. While this is about a year later than before the latest round of delays began (in early 2021 the analyst questions and concerns – I do not make this up – were about how Sapphire Rapids production in Q4’21 seemed close to Ice Lake in Q2’21).

In any case, Intel always needed Granite Rapids to compete against AMD Genoa, but this one already received its roadmap update in February (while the specs were bumped, the schedule received another full year delay). At this point, it might perhaps be considered a “win” if Intel manages to launch this one at least a few quarters ahead of AMD’s 3nm Turin. So while Intel touted Granite Rapids (and Sierra Forest) as its return to data center competitiveness/leadership (remember Pat Gelsinger’s “nip and tuck” with regards to data center leadership), it will likely need something on 18A to make a definitive statement.

Pat Gelsinger: And as I indicated, Sapphire Rapids is now PRQ’d and the ramp is underway. We are ramping the product as we speak, strong customer demand. We expect this will be our fastest ever, Xeon to 1 million units, and we’re going to push that quite aggressively, and the factories are ramping up as we speak. Obviously, this is good news for that business competitively, a big ASP uptick as well on the product. So lots of good things come.

Nvidia foundry

Intel announced that Nvidia has joined that RAMP-C program, which may be one step closer to becoming an IFS customer, which is in-line with my prior analysis based on Nvidia and Intel CEO comments: Intel: Major Nvidia Foundry Endorsement. Intel said 7 of the top 10 foundry customers are now engaged.

Capex

GAAP net capex for the year still stands at $25B, despite the massive reduction in revenue, indicating that Intel continues to move forward on its plans to build new fabs in anticipation of future growth, as well as to prepare for the “Intel Accelerated” node transitions to regain leadership. Note that this was one of my major remarks in prior analysis: a few years ago capex of $15B would already have been considered high, while now Intel is spending $10B more, despite for the time being not anticipating higher revenue than a few years ago. Hence, without this massive fab spending, the FCF for the year would have been considerably higher.

In the first 9 months, capex at over $19B is already as high as through all of 2021.

AMD Genoa

In hindsight, the damage of the 2020 7nm delay is slowly becoming visible in full sight.

Back in 2019, the plan was to reduce the disadvantage in the data center with Ice Lake-SP in 2020, then slightly overtake AMD in 2021 with Sapphire Rapids (vs. Milan), and then deal the final blow in early 2022 with the 120-core Granite Rapids behemoth, for which even the late 2022 AMD 96-core Genoa CPU wouldn’t have sufficed to catch up.

Alas, Intel is currently back to square 0. In 2019, it had to watch how AMD overtook its 28-core Cascade Lake with 64-core Rome. Currently, it is seeing how the 96-core Genoa is making the 40-core Ice Lake-SP obsolete.

Nevertheless, there is one caveat, which is pricing. When AMD entered the server market in 2017, it drastically undercut Intel on pricing, but over the years this has reversed to the point where AMD is now charging just as much (if not even a bit more) for its highest-end CPU as Intel did in 2017. This has provided Intel an opportunity to compete on pricing in the lower-end segments.

For example, for the amount of money that gets you a 32-core AMD Genoa (~$3k), it is possible to buy a 36-core Ice Lake. Alternatively, it is possible to buy a 28-core Ice Lake for less than $2k. Similarly, for about $1k, it is possible to buy a 16-core Genoa, while Intel offers a 20-core Ice Lake, or a 12-core one for just $500.

According to the latest market share report, Intel still held over 80% x86 market share in Q3.

Earnings call

Intel said in its prepared remarks that data center TAM is “holding up better”, which goes squarely in the face of Intel’s results in the last two quarters. As mentioned earlier, FPGA was up 25%.

Intel 4 and Intel 3 are our first nodes deploying EUV and will represent a major step forward in terms of transistor performance per watt and density. (…) We continue to be on track to regain transistor performance and power performance leadership by 2025.

It is still quite incredible to observe that Intel, being three years behind TSMC in HVM EUV, will go from being so far behind, to being 1-2 years ahead (as exemplified by RibbonFET, PowerVia and high-NA EUV) over the next two to three years. Of course, this is also due to TSMC having some of its own execution issues at N3 and N2.

IFS is a major beneficiary of our TD progress, and we are excited to welcome NVIDIA to the RAMP-C program, which enables both commercial foundry customers and the U.S. Department of Defense to take advantage of Intel’s at-scale investments in leading-edge technologies.

IFS further added another $1B to its pipeline. Given how the pipeline has increased to $7B over the last 7 quarters, it seems IFS is on track to become a $4B annual business.

Intel also provided a more clear explanation of the internal foundry model:

This means we will create what I like to call a new and clean API for the company by establishing consistent processes, systems and guardrails between our manufacturing teams and our business units. This will place our BUs on the same economic footing as external IFS customers and will allow our manufacturing group and BUs to be more agile, make better decisions, and uncover efficiency and cost savings. We have already identified nine different subcategories for operational improvement that our teams will aggressively pursue.

For example, product teams will be heavily incentivized to drive to high-quality A0 steppings as they see the full costs of steppings, validation cycles, hot lots and capacity changes. Factories will move to rigorous capacity loading cycles, transparency of costs for loading changes, and efficiency of capital utilization, and structural and variable wafer costs. In addition to establishing better incentives, this new approach will provide transparency on our financial execution, allowing us to better benchmark ourselves against other foundries and drive to best-in-class performance. It will also provide improved transparency to our owners as we expect to share full internal foundry P&L in calendar year 2024 – ultimately allowing you to better judge how we are creating value and allocating your capital.

Nevertheless, my initial criticism was that it was ultimately just that: a P&L model. Indeed, Intel’s announcement to disclose this P&L in 2024 further shows that. What I argued, instead, that ultimately matters most to drive cost per transistor, is simply Moore’s Law. While the new model may yield some additional efficiency improvements, the fundamental economics will always be dictated/limited foremost by transistor density and fab/equipment cost, combined with yield.

Now, this model led some people to speculate whether it was the next step towards a fab spin-off. However, Pat Gelsinger directly denied this. Instead, this new model will serve as a means to benchmark Intel against the competition. In that regard, recently following slide leaked out.

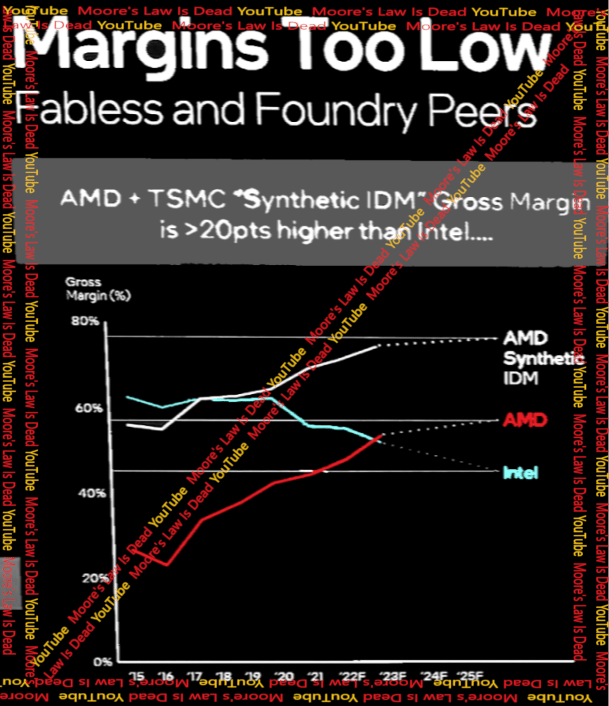

MLID

It shows how Intel’s gross margin has deteriorated while AMD’s has improved significantly, and a hypothetical AMD IDM is trending towards 80% gross margin. This explains why the leadership management is driving for these efficiency gains. Nevertheless, as the slide above shows, fundamentally this will come from leadership products on leadership process nodes to drive higher ASPs from lower cost per transistor.

So what this concretely means, for example, is that with the new P&L, the Xeon team for example will be able to compare itself against the likes of AMD (likely 50%+ gross margin) or Nvidia (60%+ gross margin), since it is being (virtually) charged the same cost for a wafer as a real (external) IFS customer. On the other hand, the IFS team for its part will also continue to compare itself against TSMC (TSM).

So basically, all Intel will really be doing is quantifying the benefit that being an IDM provides, while remaining an IDM.

Put differently, as an IDM the manufacturing team has historically “charged” the Xeon team (for example) with a relatively low wafer cost in order for Intel overall to deliver 60%+ gross margin. However, since going forward the Xeon team will internally be charged just as much for a wafer as any other external IFS customer, this will drive the Xeon team to be much more efficient in order to deliver the same (internal) gross margin that investors observe in any other fabless company (for example Nvidia nearly 70%). So if a 60% Xeon margin then stacks up with a 50% foundry tax, the overall Intel gross margin would be 70% (as Intel would be selling a CPU that costs $1 to produce for $3.3, in this example, which compares to Nvidia who would be selling a $2 GPU for $3.3).

Pat Gelsinger: And ultimately, I’m the CEO across both, and we’ll be making good decisions to hold both of them accountable even as we clarify the interfaces and the efficiencies between them.

Following was ultimately the key statement from the whole earnings call. Again, an investor isn’t buying this stock for the next few quarters, but for the potential of regaining process leadership and using the economic benefits of this position as an IDM to deliver very strong economics.

Best-in-class semiconductor companies achieve gross margin in the 60s and operating margins in the 40s, and we aim to be best in class.

Ending the IDM 2.0 discussion with another bold statement:

It’s what engineers do, and we have the best engineers on the planet.

Investor Takeaway

One thing that has become obvious over the last few quarters is while analysts and management were touting Intel as a turnaround stock, perhaps analysts hadn’t been careful enough with expressing that Intel was actually still going downhill when Pat Gelsinger took over (or at least, the competition was going uphill while Intel was staying flat at best). Even now, Intel is still a few months from production on the 7nm node that caused the CEO transition in the first place.

This means the current market downturn is coming at an unfortunate time. Nevertheless, the PC results actually weren’t all too awful, as it was mainly the data center that was just one big disappointment. Since there is no public equivalent for sever TAM units as there is for PC units, it is not really possible to quantify how much is due to market share erosion, and how much due to demand contraction, although clearly Intel did lose a lot more revenue than what AMD has gained. In addition, Intel’s gross margin remains historically low as well.

After more careful analysis of the results and the reorganization, I am not quite as bearish anymore on what this entails (the risk for a lack of funding), as it does not seem all of the investments that were started will (or have to) be undone. Much of the COGS efficiencies may “simply” come from moving down the process roadmap.

Nevertheless, although Intel still generates enough cash to fund its strategy, it does come at a cost: EPS. While I remain long-term bullish given the strategy and the execution-in-progress towards this strategy, my opinion remains that there is more downside in the near-term. Intel’s results over the last two quarters combined with the Q4 guidance indicate only around $1 of earnings power (annual EPS). While the $3B reduction planned for 2023 may add around $0.75, this still means the stock is at risk of falling further towards the low $20s or even further, in 2023.

Still, for investors willing to look a bit further out, once the economy improves, which seems could happen quite coincidental with the improvement of Intel’s tech and product portfolio, then this would provide a nice setup for a decent recovery in earnings power as Intel regains leverage from improved demand and higher gross margin from the new products.

Such an unfolding wouldn’t be too different from what I imagine for example Nvidia and AMD bulls envision as their respective bull cases. While AMD and Nvidia seem a bit more pressured on the revenue side (at least in some of their segments), Intel on the other hand is currently overcharged with R&D and capex spending. Hence, an improved economy combined with an improved product portfolio, both of which could fuel high-margin revenue growth, could generate strong alpha around the 2024-25 timeframe (and beyond).

Be the first to comment