JHVEPhoto/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

Investment Thesis

In the wake of the share decline over the past few quarters, Intel (INTC) has become an increasingly compelling investment, as it has now become decisively undervalued. Simply put, Intel is currently sacrificing near-term earnings in order to grow its factory network and invest in new emerging businesses (while strengthening its existing ones). In addition, and admittedly, Intel’s revenue is currently undergoing a nosedive, but it should be pointed out that this is mostly isolated to the PC business.

Hence, as besides this nothing has inherently changed about the profitability of the underlying business, once the dust settles and Intel returns to growth and gains leverage from its investments, the stock is likely to end up looking severely undervalued at the current price in the low $30s or even high $20s… regardless of the exact success of the turnaround being undertaken. As such, the stock is a strong value pick, with strong additional upside potential if Intel succeeds in Pat Gelsinger’s plan.

Executive summary

Although more moving pieces are discussed below, the simplest argument and indicator would be to simply look at Intel’s incredible capital intensity of 42% in 2022, which compares to the long-term target of 25% (and could likely be even lower in a no-growth scenario). This should indicate that Intel is currently simply heavily investing for the future. No, the dividend is not at risk, as without these investments the free cash flow would not be in the red. As any growth investor knows, this is called sacrificing near-term profitability for long-term growth and competitiveness (and it is what Intel should have done at least half a decade ago already).

Undervalued

In the following sections I will build up an argument for what Intel is (or should be) worth.

Declining profitability

Since ultimately a stock tends to follow its company’s financials (revenue, profitability, free cash flow), in hindsight it is probably no surprise that Intel’s stock has seen pressure over the last year.

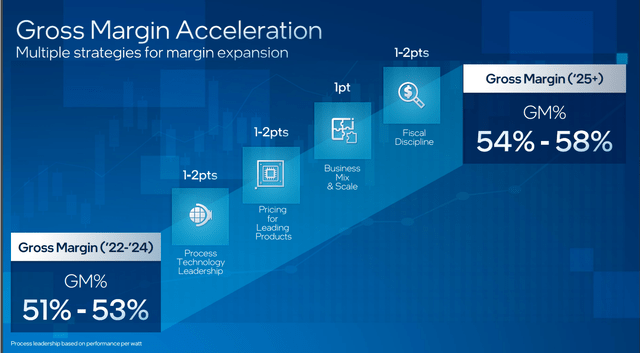

First, it is no secret that Intel’s gross margin has been cratering, which has put pressure on Intel’s profitability. This news was likely part of the reason why the shares cratered from ~$56 to ~$49 a year ago when Intel detailed the first multi-year financial details of its turnaround plan (in the wake of delaying the investor meeting due to the CFO transition).

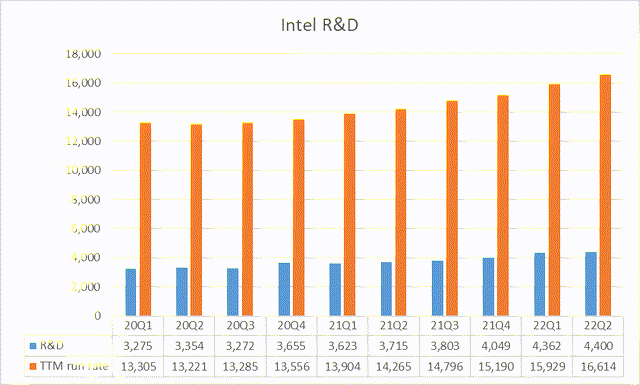

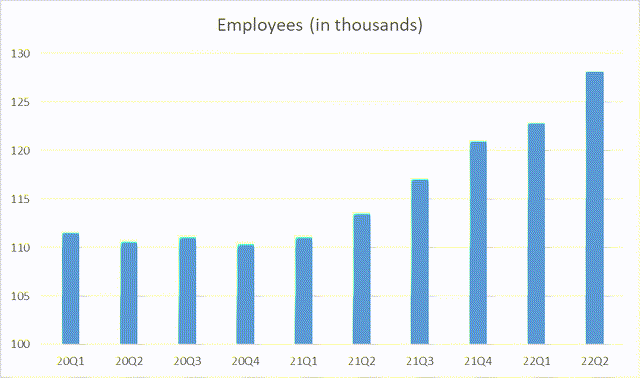

Secondly, Intel’s expenses have trended upwards as Intel has fallen behind due to technological blunders (the process node and hence product delays), likely at least in part due to underinvestment (likely due to former management overly focusing on near-term financial performance). To wit, R&D and employee count have increased rather noticeably since Pat Gelsinger joined, as well as capex.

Thirdly, while the current investments are pressuring the bottom line, the cratering of the PC market this year is now also shrinking the top line.

Economics unchanged

However, I would argue that ultimately the (unit) economics – the fundamentals – of Intel’s business are unchanged, and hence so is the long-term outlook. Since everyone agrees that Intel is in turnaround mode, I cannot prove this statement by pointing at anything going on inside Intel currently, but this should be obvious when looking at Intel’s past financial performance as well the financial performance of Intel’s peers such as AMD (AMD), Nvidia (NVDA) and TSMC (TSM).

Nevertheless, this still leaves investors with the question of what is (mostly) dragging down the current earnings power of Intel, and how worrisome this should be. In other words, are there real concerns, or is the market being myopic about the near-term downward trend (which begs for being taken advantage of by long-term investors)?

Skipping over this question and reminding investors of how big this potential earnings power really is, as a baseline Intel had a net income of over $20B in 2020/21. With ~4.1B shares outstanding, this translates into an EPS of over $5. Assigning a conservative of multiple of 10x P/E, this means Intel shares rightfully traded at $50 back then. Hence, if the earnings would recover and the multiple would increase a bit further, perhaps to 12x P/E, the shares could easily double from here.

Now, if as claimed Intel’s economics really are unchanged, then Intel in principle really should be able to return to those previous EPS figures, which means the shares could go back to where they were previously, making the premise of doubling one’s investment a reality.

Quantifying the decline

As it turns out, the answer of how feasible this actually is… is nuanced. As just argued, at least part of why Intel got itself into so much trouble is arguably because it invested too little, which made it vulnerable to a resurgence in competition.

To that end, Intel is currently well on track to add $5B in annual R&D expenses. So to understand why this complicates matters, as a thought experiment, if Intel had done so already in 2020/21, then this would have reduced earnings by around $5B, reducing EPS by up to 25%. But this in turn implies Intel really “should” have traded (to approximation) all along in the $40-50 range instead of $50-60. Ouch.

This shows that saying Intel simply has to return to its previous share price is misleading, since the present clearly shows that Intel as a matter of fact underinvested in its business. Else by definition it wouldn’t have got itself into so much trouble competitively.

Even then, though, the current low-$30 price is still significantly below what a healthily R&D-investing Intel “should” be worth ($40-50). So what gives? Clearly the discrepancy still has not been fully accounted for.

The second major item to highlight in that regard is the gross margin, which has declined by about 10 points. Indeed, if one assumes Intel had only 50% gross margin in 2020, then this would have cost Intel well over $5B in earnings.

The sum earnings cost of R&D increase and gross margin decline is over $10B, which halves the EPS. Now we have indeed squared the circle: if Intel had earned only $2.5 in EPS in 2020, then a price of $30 seems fairly valued for a slowly growing company at best.

Opportunity

However, there is a major catch, as here the first signs of a contradiction appear and should raise a major red flag: Intel spending an additional $5B in R&D to maintain leadership cannot (or at the very least should not) be reconcilable with a mere 50% gross margin.

Clearly investors should still expect Intel to return to its 55-65% long-term target, which is indeed Intel’s (long-term) plan. To be clear: this means the stock has the potential to appreciate by about $1 EPS and hence about $10 in value once Intel recovers its historical margin profile.

Gross margin decline

While it is easy to draw the path to recovery in a PowerPoint, it does warrant some discussion. In particular, while clearly regaining process leadership should be seen as a proxy for being able to recover the margin erosion from the last two years, this alone is not sufficient.

First, as a reminder, the reason process leadership equals gross margin leadership is because Moore’s Law is an economic law that is ultimately about the cost per transistor declining. (If it didn’t, then a doubling of the transistor count would simply double the cost of a chip.) Hence, with a process leadership a fab can use its cheaper transistors in such a way that it splits its chips into (1) a bit more performance (correlated to more transistors per chip) for its customers (versus competitor chips) while (2) also having a bit more profitability per chip (versus competitor chips).

This is a similar trade-off in how a chip designer can decide to use the higher performance per watt of leading edge transistors to deliver either (1) much more performance, (2) much less power, or (3) a bit more performance combined with a bit less power.

Secondly, investors should be reminded that Intel’s lower gross margin isn’t just because it has lost its process leadership. In fact, at the time of writing there are still no PC nor data center CPUs in the market built on 5nm process technology, which means that Intel is actually on par to the competition in process tech.

Instead, the main reason for the low gross margin is arguably the cost structure of the 10nm node. As the former CFO had warned investors of since 2019 already, 10nm would never achieve the very high margins of the overused (and hence quite depreciated) 14nm node that came before. Even if 10nm by now is also getting old, the issue remains that Intel has never been able to achieve the yield (defect density) that it has historically been able to achieve, offsetting any theoretical cost advantage of the node.

Note that the solution here is to leverage the EUV lithography equipment from ASML (ASML), which TSMC has been doing since 5nm in 2020. This is indeed what Intel will start doing at Intel 4 – Intel has previously attributed the Intel 4 delay due to using too little EUV.

Thirdly and lastly, note that the fast transition from Intel 4/3 to 20/18A means that there will be a prolonged, almost continuous, period of (1) factory start-ups, which were historically years of lower gross margin as Intel prepared for the Tick in Tick-Tock, and (2) both of these nodes will hence also be quite early in their yield learning curve, which means there will be little volume on depreciated nodes to act as buffer for the gross margin decline (with the only “buffer” being the costly, mediocre yielding 10nm node).

In summary, Pat Gelsinger wasn’t kidding when he said regaining process leadership is Intel’s “true North Star”, as this allows for a flywheel that will act as rising tide to lift all boats. To wit, process leadership by definition (although Intel for now has defined it as performance per watt) means lower cost per transistor than the competition. In addition, the performance per watt benefit of leadership transistors will allow to create leadership products for which Intel can then charge leadership (premium) prices. Meanwhile, the widespread adoption of EUV, and even being the first to introduce the next-gen “high-NA” EUV in high-volume manufacturing, should improve the yield learning rate and defect density.

The magic act

Which brings me to the third point for why Intel’s financials are deflated. Intel is not just investing on the R&D side, but also on the capex side in anticipation of future growth. In essence, Intel is taking a page out of the growth stock playback by already spending as if it were a $100B company, despite achieving just $80B revenue in 2021 and guiding for $65B in 2022 (including a $5B decline from the NAND sale).

As investors know, Intel is investing in three emerging businesses in particular, which I’m sure Pat Gelsinger aims for to become at least $10B in size each by 2030 or earlier: (1) the gaming and AI business, (2) Mobileye autonomous driving and robotaxis, and (3) the new foundry business. Assuming these each become $10B in size, then indeed Intel would be a $100B company without requiring any growth from its three main businesses (PC, data center and network/edge). However, Intel is aiming to also grow the latter two, with data center being work in progress, at double digits, so Intel could eventually still become much larger in size.

To quantify this, remember how the increasing R&D and declining gross margin each represented over $5B in earnings loss. In contrast, capex alone has surged from $14-19B in 2020-21 to $27B gross capex in 2022. This means capex has increased by $10-15B, which explains why the free cash flow is becoming negative in 2022, with no recovery expected until 2025.

Tying this back to the previous discussion about process leadership, there are several reasons for this. First, Pat Gelsinger once said Intel had simply underinvested in fabs (which explains the shortages in 2018/19 and again in 2020/21). Secondly, as mentioned above in order to regain process leadership Intel needs to introduce nodes at a much quicker pace, which means Intel will need to start preparing 20/18A very quickly after 4/3. Both of these nodes will also introduce substantial use of EUV for the first time in an Intel fab. These are $140M+ tools. Thirdly, the fab buildout in anticipation of future demand, which I have recently discussed in more detail here: Intel Stock: World-Class Financial Engineering (NASDAQ:INTC).

While Pat Gelsinger currently looks like the bogeyman, guess who will be the last to laugh once Intel has secured a long list of top-notch foundry customers (including the likes of Qualcomm (QCOM), Cisco (CSCO) and Nvidia (NVDA)) in the back half of the decade, eagerly willing to fill Intel’s fabs with demand for its newfound industry-leading process tech. Nevertheless, for the purpose of this article this should be seen as additional upside not present in the base case.

Overall, Intel’s capital intensity in 2022 will be an astonishing 42% ($27B on $65B revenue). For comparison, Intel’s long-term guidance is for 25%. This confirms the above statement that Intel is currently investing as if it is already a $100B revenue company. Alas, since investors are currently only seeing the cost part of being a $100B company without the actual returns, the stock is getting hammered. Nevertheless, even in the worst-case if the forecasted demand does not quite materialize, then by the end of the investment period Intel will still be back to process leadership (or clear parity at worst) and the capital intensity will drop in order to match the true demand levels.

This, ultimately, is what I meant by economics remain unchanged: there is simply no way capex would indefinitely remain at 42% of revenue in the worst-case no-growth scenario.

In addition, due to the E.U. and U.S. CHIPS Acts, Intel is currently able to build fabs at a historical discount. If Intel gets the full 30% offset, then it will be building multiple $10B fabs for just $7B. Needless to say this improves the underlying economics even further.

Preliminary takeaways

Pat Gelsinger asked for and got the unconditional support from the Board, and the current investment period shows exactly why. After being overzealous with stock buybacks in the last half a decade, Intel has now become a stock for the patient, and needs to spend literally tons of money in order to catch up on R&D underinvestment, regain its once unquestioned process leadership, and build fabs to cater to future demand that neither analysts not investors are willing to bet will really materialize.

Nevertheless, the analysis above has shown that Intel has more leverage than it may seem. While obviously the increase in R&D is a must, on the capex side Intel is at an obscene 42% intensity in 2022, in order to prepare for the items just mentioned (process leadership and future demand/growth). This is just a fact of the turnaround plan and investors should simply and must only accept that Intel is not investing in tulips or NFTs, but in real fabs that in just two years from now will start outputting vast volumes of literally industry-leading 20A and 18A wafers.

Once those wafers get assembled into full products, it should become obvious why Intel is making these current investments, even if to the present-day observer it all looks like black magic at best. Maybe because it is back magic.

Reality check

As of September 2022, all nodes through 18A still remain on or ahead of schedule, as has been the case for the last 24+ months. As proof points:

- Intel 4 will start ramping in the coming months, so the visibility here is great, although some (unconfirmed) rumors (FUD?) say that Intel 4 is trending behind in terms of yield.

- Intel said the progress of Intel 3 was the reason to forward-port Granite Rapids and Sierra Forest to this node. DCAI exec Sandra Rivera seemed to indicate that this is one of the nodes ahead of schedule: “But we also knew that we were actually executing a bit ahead on the process technology road map and the opportunity to leverage the Intel 3, the higher-performing libraries and to get more performance on the Granite platform.”

- Sandra Rivera also said 20A and 18A are ahead of schedule: “Intel 4, ready for production end of this year with our client product; and then Intel 3, derivative of Intel 4; and then 20A and 18A all are ahead of schedule.”

- As proof point of 18A being ahead of schedule, in February Intel pulled in 18A from “early 2025” to H2’24.

- Intel has mentioned that starting in the second half of 2022 it is expecting multiple test chips, including from foundry customers, in particular on Intel 3 and 18A (which are going to be the high volume nodes).

- As a counterfactual, if Intel really was struggling with RibbonFET and PowerVia, there is really no way in which Intel could say with a straight face it is “on track” (never mind “ahead of schedule”) to start manufacturing 20A in around 18 months from now.

This is the plan for which Intel is spending tons of R&D (both for the fundamental technology as well as for the products that will populate these fabs and nodes, to have the products ready when the process is) as well as capex to have the fabs ready to ramp when the process is.

To come back to the sixth point, an internet user recently pointed out the by now obviously underappreciated turnaround of being able to start 20/18A production in 2024:

The same Intel that can’t get any EUV chips out the door until next year, is suddenly going to race past everyone and do that and implement a new transistor type and restructuring of the entire silicon stack in the next 24 months? Does anyone seriously believe that?

The answer is, yes.

Financial modeling

Investors may be looking to test the theory above in terms of possible financials, which are summarized below.

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2026 |

2026v2 |

2030+ |

|

|

Revenue |

72.9 |

74.7 |

65.0 |

121 |

100 |

100 |

|

Gross margin |

59.4 |

57.7 |

49.0 |

56.0 |

56.0 |

60.0 |

|

R&D |

13.6 |

15.2 |

18.0 |

22.0 |

22.0 |

22.0 |

|

MG&A |

6.2 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

|

Operating margin |

33.4 |

29.7 |

11.3 |

32.4 |

27.5 |

31.5 |

|

Tax rate |

16.6 |

9.1 |

8.0 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

|

Net income |

21.6 |

22.4 |

6.8 |

34.6 |

24.2 |

27.7 |

|

EPS |

5.1 |

5.47 |

1.66 [2.57] |

8.4 |

5.9 |

6.8 |

|

GAAP cash from ops |

35.4 |

30.0 |

21.0 |

54.5 |

45.0 |

|

|

Capex |

14.3 |

18.7 |

23.0 |

30.3 |

25.0 |

|

|

FCF |

21.1 |

11.3 |

-2.0 |

24.2 |

20 |

Let’s carefully walk through this table which displays standard earnings disclosures.

The first two columns are historical non-GAAP performances from 2020 and 2021 for comparison. As discussed, R&D spending is low so EPS is high.

The third column displays the guidance for 2022. It neatly shows how lower revenue, lower gross margin and higher R&D are together conspiring to decrease the operating margin by 20 points (two-thirds). Note that the EPS as calculated from this table is lower than Intel’s guidance. The GAAP guidance is displayed in square brackets; the non-GAAP guidance stands at $2.30.

The next two columns (2026) are based on Intel’s guidance at investor meeting in February. The first column is based on $121B revenue, but this is likely for illustrative purposes only: there was a graph in the CFO presentation that had bars for 2021, 2023 and 2026 revenue, and $121B revenue is the result of assuming those revenue bars were to scale. However, Intel has not explicitly guided to this number for 2026, and a small reality check shows that $121B revenue in 2026 is impossible, as Intel’s guidance is at most high single digit growth in 2023/24 and low double digit growth in 2025/26.

Hence, the most realistic bull case would be $100B revenue in 2026 with 56% gross margin as the midpoint of Intel’s long-term guidance. Of course, note that $76B revenue in 2022 is used as the baseline, so it may be necessary to remove ~$10B if $65B becomes the new baseline.

Since this may scare some investors, remember that the decline is mostly due to the PC decline, which changes absolutely nothing about Intel’s ability to grow its emerging businesses. In other words, estimating Intel’s revenue is not possible just by assuming some CAGR, but instead comprises a sum of six individual parts. In other words, since PC was always the slowest growing segment, then if anything the PC decline either increases Intel’s likelihood of hitting its target growth rates, or even to surpass them.

Lastly, the final column shows a possible long-term scenario with $100B revenue in 2030. Assuming Mobileye, GPU and foundry each become $10B+ in size, this is certainly feasible, especially if NEX and DCAI keep growing at their intended rates. (A base case scenario for 2030 that I made in 2020 was targeting $120-140B, with the upside case approaching $180B.)

Overall, the message here is that even when being generous with the R&D spending and tax rate, and being fairly conservative with the gross margin and extremely conservative with the P/E multiple, Intel (as expected) should be able to achieve sufficient leverage as it approaches $100B revenue, and deliver new all-time high EPS results over time.

Let’s emphasize again that none of this requires any heroic assumptions. None of this is assuming any kind of turnaround, just a return to historical execution (on increased R&D). For comparison, the semiconductor industry is forecasted to double to $1T by 2030, while none of the suggested models above come anywhere close to that performance… Except I suppose if one extrapolates further double digit growth from the 2026 models, then Intel could indeed double its revenue by 2030.

Obviously, though, at this point doubling revenue just be regarded as a stretch goal beyond the current goals, beyond the scope of this article. Nevertheless, philosophically speaking, if Intel becomes successful in all three of its new businesses, then Intel will have effectively doubled the amount of full-blown businesses it has, so doubling revenue over the next 10-20 years shouldn’t be completely unfeasible, unrealistic or unthinkable either.

But overall, to summarize, even in the low-growth scenario where Intel slowly grows to ~$100B by 2030, it should be possible to deliver over $6 EPS, which would double the stock price given a “best-in-class” 10x P/E multiple. A more average 15x multiple would entail a $90 PT. A turnaround scenario would entail (as Pat Gelsinger informally touted in February) doubling earnings (>$10 EPS), yielding triple digit price targets.

Risks

While the capex leverage is de-risked due to the CHIPS Act and at worst simply managing fab investments to where the demand signals are, the main risk is that the ongoing increase in R&D will obviously continue to eat away the artificially inflated EPS of the last half a decade. So to be clear, while the thesis of this article is simply to return to the high-end of the range where Intel has traded at over the last few years, this will require some revenue growth (from a combination of existing and emerging businesses), but this is also what Intel is investing in.

In other words, something that investors perhaps missed, which is an unsung insight, is that the turnaround isn’t just about Intel regaining process and technology leadership, but also to reaccelerate the growth (Intel actually had a fairly reasonable growth from 2015-2021). Although it is obviously a coincidence that current macro environment (financial bottom) coincides with the technology bottom (the end of 10nm, just before the ramp of Intel 4).

Secondly, the risk is also in mistiming the bottom of the turnaround. The bottom wasn’t when Bob Swan was kicked and Pat Gelsinger joined; as just mentioned the bottom is… now.

How can one be this certain about the bottom? The observation that 20A is “on track” to ramp in around 18 months, and the stock now being down by well over 50% vastly increases the likelihood of being close (enough) to the bottom. Remember also how above a case was made for Intel being worth ~$30 in the case of ~50% gross margin and inflated R&D spending. (Since Intel as discussed has a clear path towards gross margin recovery, it is already undervalued at $30.)

Thirdly and lastly, some investors may take issue with the statement that $100B revenue over time is realistic. However, while some of Intel’s businesses are still quite small, the market opportunity in IoT, 5G networking, data center, data center accelerators and AI, graphics and HPC, robotaxis and autonomous driving, and foundry are enormous. Intel is clearly indexed to nearly all of the semiconductor growth segments (aside from PC).

Investor Takeaway

Although admittedly I have been an Intel bull for far longer than the most recent stock decline, the “beauty” of the share price plummeting over the last few quarters is that it is becoming increasingly easy to make a bull case for owning the shares (as being objectively undervalued currently) and delivering market-beating returns.

Previously, one would have to be convicted in the turnaround, but now it “simply” suffices for the stock to return to a price it has traded at before, which means the stock could/would double.

As argued at elaborate length, the reason this is possible is because none of the Intel fundamentals have changed, which means this former price range shouldn’t remain out of reach forever. The ingredients that will make this possible are leverage in both revenue and gross margins as investments start to yield results over time. (Note that due to underinvestment under prior management, which artificially inflated EPS, admittedly Intel perhaps never had a business trading in the $50-60 range to begin with, so some revenue growth is indeed required.)

As case in point, even in the worst-case scenario where Intel was underinvesting by $5B annually, this still leaves the conclusion that Intel is undervalued, since it really should be (or should have been) trading in the $40-50 range, assuming a very conservative 10x P/E multiple. Note that in such a “proper investing scenario”, Intel likely would not have dug itself into such a disastrous hole technology-wise in the first place, so the gross margin would still be around 60%. Alas, in the real world Intel currently has to heavily spend to catch up while the gross margin has also declined by an abysmal 10 points, never mind the top line also contracting by $10B due to a recession.

This is obviously why it is called a turnaround. It’s just that people may have (incorrectly) assumed that Intel had already bottomed when Pat Gelsinger became CEO. Even in the 2019 investor meeting plan (where Intel would deliver $85B revenue and $6 EPS by 2023/24), gross margin would bottom only in 2021 to 57% (without there being any guidance yet for gross margin beyond 2021) due to the “confluence” of 10nm/7nm nodes. Obviously, due to the 7nm delay, this confluence has been postponed by two years to 10nm/7nm/5nm (7/4/20A) in 2023.

In any case, Intel has a solid path to deliver all-time high EPS in the back half of this decade as it regains technology leadership as well as achieve leverage from its investments in R&D in new and existing businesses and new fabs, reaching triple digit billion dollar revenue. Let’s emphasize again that no black magic is necessary, just regaining a solid technology footing (and conservative growth from a combination of existing and emerging businesses). If one then assigns a 10x multiple on let’s say $6 EPS, then Intel will have doubled your capital – ignoring any additional dividends. Of course, in the real turnaround case if Intel gets lucky to get a >15x multiple on $10+ EPS… Valuing Intel Like Its Peers Yields A $210 Price Target.

I am putting a firm stake in the ground by claiming that currently is the financial (gross margin and revenue) and stock bottom. (The tech bottom will last another year as AMD starts rolling out its Zen 4 line-up and Intel 4/3 volume remains minimum until H1 2024.) If the stock does go lower, then that would simply only increase the gift the market is providing, as it was determined above that even a low gross margin, no growth and highly investing Intel would still be worth $30.

Of course though, odds are a highly investing Intel will eventually see gross margin and revenue expansion. Hence, I have more than doubled my (still relatively small) Intel investment over the last few months by taking advantage of this dip.

In conclusion, with the share price cratering, I am simply making the case Intel’s fundamentals remain unchanged (as long as the return to process leadership or even parity remains unchanged, which it is). This in due time should warrant a >$60 share price (assuming a meager 10x P/E multiple) as the revenue approaches and/or succeeds $100B over time. This is because, after half a decade of focusing on reducing costs, Intel is currently investing as if it already is such a $100B company, sacrificing near-term profitability for the long-term growth and health of the business.

Be the first to comment