Phira Phonruewiangphing/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

Introduction

By now, it shouldn’t come as a surprise, as the highly anticipated Ethereum (ETH-USD) Merge is finally happening on September 15th. It is a historic event for the cryptocurrency industry, and it will change not only the economics of the Ethereum Network but the status quo of the industry as a whole.

Quick Merge Recap

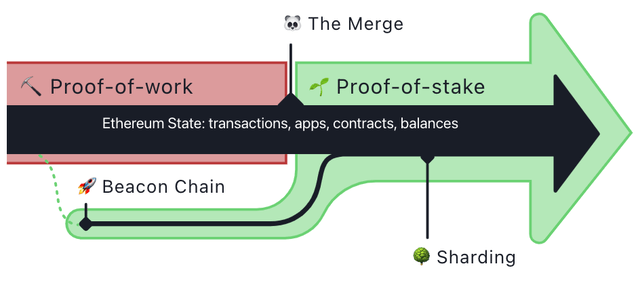

Ethereum’s Proof-of-Stake (PoS) chain (i.e., the Beacon Chain) has been live since December 2020, running side-by-side with the Ethereum standard Proof-of-Work (PoW) chain (that everyone currently uses). The “Merge” will put an end to this double-chain period, and the event will mark the Ethereum transition to a fully PoS chain.

ETH Issuance Rate

As of today (September 13th), the Ethereum PoW and PoS chain still operate in parallel. However, it is currently not possible to use the PoS chain, and if you were to send a transaction on Ethereum right now, it would still execute on the PoW chain. Nonetheless, validators on the PoS chain are already getting rewarded for securing the soon-to-be fully operational PoS network. This situation leads to two separate sources of ETH issuance:

- Validator rewards on the Ethereum PoS chain, and

- Miner rewards on the Ethereum PoW chain.

After the Merge, PoW miners will stop operating, eliminating miner rewards. Finally, validator rewards will remain as Ethereum’s only source of new Ether issuance.

The Magnitude of the Impact

It should be already clear that the transition from Proof-of-Work to Proof-of-Stake impacts ETH’s issuance rate. Ether’s nature is inflationary and currently, 2 ETH get printed every block (roughly every 13 seconds) to go to miners. Once Proof of Stake is adopted and the Proof of Work system is left behind, the Ethereum network will be hit by an evident supply shock. After the merge, the yearly ETH issuance will decrease from about 4.9 million ETH (~4.13% of outstanding supply) to an estimated 0.6 million, or ~0.49% issuance (with 13M staked ETH projected).

If we stopped here, we would only be scratching the surface. The implications go much deeper and require uncovering the network’s economic dynamics.

Ether Issuance – Market Dynamics

Despite its inflationary tendency, ETH can become deflationary. If you ever used the network, you already know that executing a transaction on Ethereum requires paying a fee. Transferring Ether between wallets, using a Decentralised Finance (DeFi) protocol, or creating an NFT are all actions that involve paying a fee. These transaction fees are the so-called ‘gas fees’, and play an important role in ETH issuance rate.

Due to a mechanism implemented with Ethereum Improvement Proposal (EIP) 1559, the gas fee structure is split into two parts:

- A base fee, set by the Ethereum protocol, and

- A priority fee, a tip set by the user to expedite the execution of the transaction.

The base fee varies according to the demand for blockspace. In other words, it varies based on how much users want their transaction to be included in the next block (and have their transaction executed quickly). The peculiarity of the base fee is that it is burned, or removed from circulation, rather than rewarded to miners or validators. As mentioned in the above bullet point, the base fee is set algorithmically by the protocol itself, and the Ether burn rate is not a fixed, hardcoded parameter. The base fee targets 50% full blocks, and it will increase or decrease by up to 12.5% after blocks are more than 50% full. In simpler terms, the burn rate is dictated by how much the market values Ethereum’s blockspace.

A takeaway from the above is that Ether is inflationary at its core, but there are also deflationary forces coming into play as usage of the Ethereum Network increases. Heavy activity on the network will cause higher base fees, and as base fees are burnt and removed from circulation, ETH supply is reduced. So can Ether become deflationary, despite inflationary rewards being continuously issued to validators? The short answer is yes. However, there are multiple variables in play.

Base Fee Threshold

As previously mentioned, Ether becomes deflationary if the network is heavily used, and ETH is actively spent on gas fees to execute transactions. The level of activity that will cause the network to become deflationary, and therefore ETH to be more valuable, can also be quantified. In fact, by taking the ETH issued to validators in a specific number of blocks, and the total amount of gas spent on transactions in those blocks, we can calculate the threshold base fee at which the burn rate is greater than the issuance rate, causing the circulating supply of Ether to decrease.

Based on the current number of validators and historical gas consumption, this base fee threshold is estimated to be 15.43 gwei. For context, the 15.43 gwei threshold base fee is at the lower end of the gas fees range observed over the last year (10-200 gwei). Based on past data, periods of deflationary issuance seems very likely to occur in the near future. However, in the long run, the behaviour of informed actors that make up the market will also play a major role in establishing inflationary or deflationary trends.

Market Participants Expectations

The Ethereum economic system is designed for a negative feedback loop to naturally establish. Think about the EIP1559 mechanism described above. The more people use the network, the lesser the Ether issuance, as more Ether gets burned when gas fees are high. Lower issuance, from basic economic theory, will then eventually lead to a higher Ether price. In turn, this expectation of profit due to high asset prices will cause people to hold on to their Ether, rather than spending it on transaction fees. Thus, less usage will lead to a smaller burn rate and more issuance, which in turn means a lower Ether price. Expectations for increased dilution translate in a deterioration of holding incentives, which completes the cycle leading to the higher usage starting point.

The cycle is the following: Less usage -> more issuance -> lower price -> lower incentive to hold -> higher spending -> more usage -> less issuance -> higher price -> more holding -> less usage -> and so on.

What this cycle describes is a self-correcting mechanism that provides an all-season, multi-party incentive mechanism. This self-correcting mechanism converges to a proper valuation of Ether given the value of Ethereum’s blockspace.

ETH Blockspace Value

Blockspace can be considered the commodity of cryptocurrency networks. As the size of a block is capped, there is a limited number of transactions that can be executed (included in a block) at a given time. In addition to the inconvenience of having to wait for transfers of assets, a slow transaction can incur negative externalities such as being subject to market volatility, front-running, and missed short-window opportunities (e.g., limited supply NFT minting). Fees users pay to execute transactions are a reflection of their willingness to acquire timely space in a block, giving blockspace an implicit time value.

We can evince from above that blockspace value is mainly determined by user demand. But what drives user demand? I would argue that security (including decentralisation), performance (e.g., speed, capabilities), and community are the main drivers of user demand for blockspace.

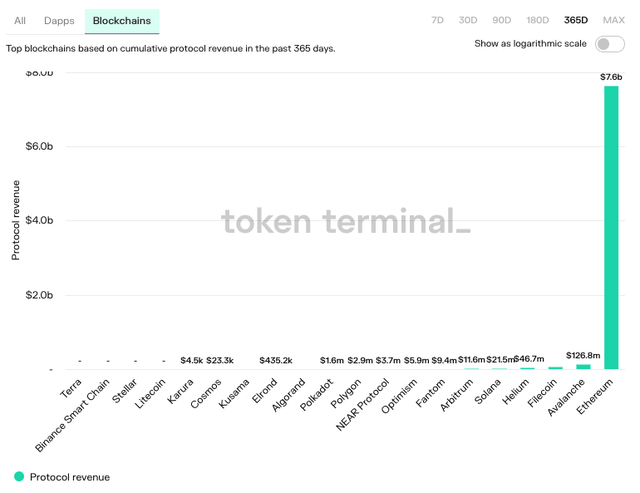

Ethereum’s blockspace is currently the most valuable in the industry, with the protocol accumulating more protocol fees than all the competitors combined.

Protocol Revenues by Blockchain (tokenterminal.com)

Blockspace fees are essentially the blockchain revenue of Ethereum. If enough fee revenue is collected, miners/validators do not need as many newly issued Ether as rewards to cover expenses. This is an important point, because blockchains constantly printing more coins risk over-inflating their supply, leading to a decrease in the value of their native asset.

A decrease in the native asset value is never a net positive for blockchain networks, whether they are powered by Proof-of-Stake or Proof-of-Work. In a PoW Ethereum, more valuable Ether equals more valuable mining rewards, which in turn attract more miners and hashrate, rendering 51% attacks more expensive. In a similar, more direct way, in soon-to-be Ethereum PoS a more valuable Ether equals a more valuable staked ETH, which renders acquiring enough ETH to attack the network more expensive.

As a summary, blockchains overall benefit from their native asset being more valuable. The more people are willing to pay for blockspace, the more Ether gets removed from circulation (burned). As Ether becomes more scarce, its value increases, which in turn contributes to more network security. The opposite is also true, and when demand is low and issuance increases, Ether price decreases.

However, when Ether price is too low, the threshold to burn more Ether gets lower too. How does this work in practice? Let’s say that an Ether transfer currently costs 20 gwei. 20 gwei means an ETH transfer costs around $0.60. The same $0.60, should Ether double in price, would result to a base fee of ~10 gwei. This example shows how the system is sustainable even with Ether increase in price. With an increase in Ether value, less Ether gets burned, and the network reverts to its inflationary nature.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Ethereum will decrease Ether supply, and deflationary forces will be beneficial to all actors of the network. Deflationary periods are likely to put positive pressure on Ether price, which in turn will increase the network security. As performance is upgraded, and the community expands, it seems very likely that the Ethereum blockspace will become more valuable in the long run, maintaining its position as the leading smart-contract-enabled blockchain. This will not be possible without the economic feedback loop described above, which will provide a sustainable economic model to incentivise all actors in periods of both economic expansion and contraction.

Be the first to comment