BrianAJackson/iStock via Getty Images

Macroeconomic effects on corporate finances

This piece worries about the effect of macroeconomic changes upon corporate finances. This means that we’re using that bit of economics where we’re pretty sure we don’t know very much – macroeconomics – to examine that part where we’re pretty sure we do know quite a lot – the microeconomics of markets and market participants. The result of this is that there’s a large amount of uncertainty here. Almost getting into handwavy territory.

Another way of putting this is to insist that there’s a lot of room for interpretation here and quite possibly no one “right” answer. A lot will depend upon opinion therefore. With that in mind though.

The first thing to note here is that the liquid stock for British Land is the London quote. But BTLCY is liquid enough – and tracks London well enough – for dollar investors. BRLAF is very illiquid and we can see that from the jerkiness of price movements let alone the recorded volume.

We should also note that the actual financial results aren’t all that good. Sure, rents and income are rising, (from the latest accounts, ” We delivered 5% like for like net rental growth ” but that’s significantly below the inflation rate) but property values themselves are falling (this is what ” Higher interest rates have increased property yields” means) and the portfolio seems to have dropped 3%. Underlying profit is up but that’s not what really matters in a property company.

There’s a big problem for the varied commercial property companies.

The problem

As I’ve noted before about British Land, we’ve got a structural problem. The sector rolled along for decades assuming that values could only go up as would rentals. In fact, the standard lease worked on an “upwards only” basis. There never would be a fall in (nominal) rent at all. Read the section starting “Peculiarities” in that earlier piece.

What this means is that the British commercial property companies have traditionally been rather more geared – for which read “borrow more” – than might be wise. Wise if we include the possibility that property values and rent rolls can in fact fall. This is what killed Intu (the property company, not the American software one). The assets were worth something – quite a lot actually. But when asset values started to fall, caused by falling rents under the onslaught of internet shopping, those asset values – and the rent as cash flow – failed to support the debt burden. Being geared is great in a rising market, it’s a death trap in a falling one.

Okay, so first retail prices started to fall, based upon that internet shopping experience. Then covid caused a leap in work from home which affected office space. Sure, many are coming back now, but overall demand for office space is decidedly lower than folks were predicting it would be a couple of years back. That’s lowered the price.

Now, it looks like British Land (as with the others, Hammerson and LandSec) have avoided the Intu fate. They’re not going to get crushed by the pincers of falling asset values and debt burdens. But there’s also nothing very exciting about their current position either. The best we’d expect, without any speculation here at all, is a struggle to pay down debt to better match those – at best – fragile asset values and rent rolls.

Ah, but, inflation

But there’s another issue here which is inflation. What’s the usual protection against inflation? To own real property which sort of, around and about, matches the price changes in the economy in general. And if you’re financing that at interest rates which are lower than inflation, then you might make out like a bandit.

And that’s the part that I don’t think has been properly explored. That interaction of rising interest rates and inflation.

That interest rates are rising is obviously true – the Bank of England raised them again today (the day I’m writing). So, carrying debt becomes more expensive. Except, again from the accounts:

- Interest costs fully hedged for the next year and 77% of projected debt is hedged on average over the next 5 years

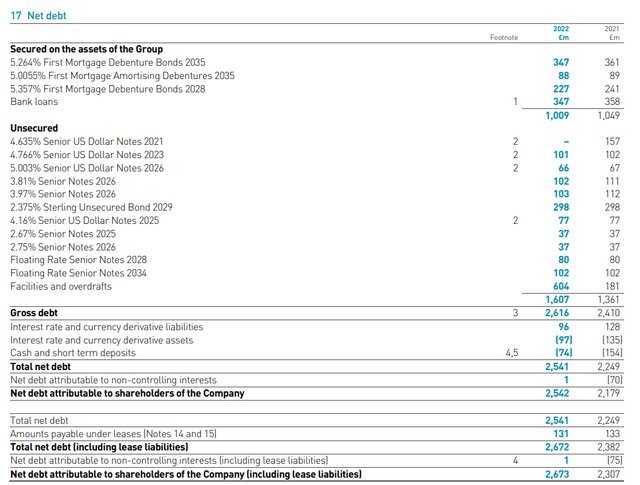

There’s more detail on this in the annual accounts:

Debt at British Land (British Land)

The bank loans and the floating rate notes are, of course, at market and floating rates. But all the rest of the debt is at fixed rates. Call that £1.1 billion at floating rates and the rest, £1.5 billion at fixed rates. Around and about – good enough detail for us here.

Now, note that UK inflation is currently running at around 10%. Interest rates are nominally some 4% or so. Maybe a little higher for a commercial risk like this. We’d not go far wrong in stating that real interest rates for British Land are currently minus 5%.

Oh, Okay. So we hold real property, on a geared basis, and we’d expect that real property – and the rent rolls – to keep up with inflation. OK, sure, we can have that structural decline as a result of the internet, but as a cyclical phenomenon we do expect rents and values to keep track of the inflation rate. But our outstanding debt is shrinking by 5% a year. Or, perhaps, the real value of it is.

The questionable bit

The bit that’s difficult here is how long this is going to last. Sure, it’s obvious that the debt burden is being lightened by the inflation of this year. But how long is that inflation going to last? There are those who say that the Russia/Ukraine/energy prices effects will start dropping out of the inflation numbers this coming spring. So it’s a once off change in the price level and that’s that, done and dusted.

Then there are those like me who are more monetarist in our approach. Or perhaps less enamored of modern progressive economics like Modern Monetary Theory. Us old crusties tend to be a bit more skeptical about that. Massively increasing the money supply, as QE has done, is going to lead to substantial inflation. Weirdly, at first at least, rising interest rates are going to further increase the money supply (the effect is that at near zero no one really bothers about deploying their money to gain interest. As interest rates rise they will – increasing the V part of MV=PQ) and so have an upward effect upon the inflation rate.

There’s also that possibility of an old fashioned wage/price spiral as the strikes actually win those pay increases. At which point we might say that inflation is embedded and will be with us for a number of years.

Now, the traditional cure for that is to raise interest rates again. But today we’ve seen that other method – reverse QE and so reduce the money supply directly.

Hmm, now

We’re in macroeconomics which is that area of economics where everyone already disagrees. But my read of this is that, if inflation is this one year only thing, then British Land is about correctly priced as is. However, if inflation stays high, then that debt burden is going to be eaten away pretty quickly. And I certainly don’t expect interest rates to be raised up to the 8 or 10% nominal level which would even match inflation or even produce a positive real interest rate. I would expect QE to be reversed to reduce the money supply instead (yes, obviously, that would also raise the interest rate but not by so much).

So that’s the idea

If inflation stays high, then British Land looks better and better. That fixed rate debt inflates away making the equity look more and more attractive each year inflation stays high.

Yes, obviously, we have all the other problems still – will people really return to the office, might we have some vast disaster of a recession, and so on. But those things are already built into the price here. I’m deeply unconvinced of what the effects of inflation on the debt burden are. So, it’s possible to conclude that there’s an undervaluation here, dependent upon views on inflation and interest rates.

Why I’m Wrong

One obvious possibility is that this inflationary effect upon debt burdens is already built in. But I don’t really see that, I’m certainly not seeing it mentioned anywhere.

Another is that inflation is just a this year thing and so, while the effect has happened, it’s not all that large.

Finally, there’s always the possibility that interest rates really rise in the next few years and that rolling over that debt is going to be significantly difficult.

My View

I think there’s a good possibility here that the effects of inflation on that debt burden are being underestimated. I also think that inflation is likely to be more persistent than current market evaluations. The end result of this is that I think that British Land – as perhaps with some others – is going to find its debt to equity ratio improving considerably over the next few years. That increases the value of the equity, all other things being equal.

The Investor View

Borrowing money at negative real interest rates to invest in real property is usually a good way to make money. It’s also true that inflation disposes of the real value of the debt burden. High real interest rates work the other way, crippling those who are holding assets that only rise at the inflation rate.

So, that’s the observation. I think – I think – that negative real interest rates are going to persist. This is good for commercial property companies.

There is, after all, a reason why real property is considered an inflation hedge.

Be the first to comment