Justin Sullivan

Headlines on Bank of America (NYSE:BAC) third quarter earnings ranged from positive to enthusiastic and for the life of me I can’t figure out why. Their comparisons to Q3 2021 were negative by the most important measures. Their net income was down Y/Y from $7.7 billion to $7.1 billion. Their per share earnings fell from $.85 to $.81 (a “beat” against estimates of $.78). Their return on total assets, an extremely important measure of bank performance, fell from .99% to .90%. Staying close to 1% return on total assets is an important measure for banks. Dropping almost 10% is a very meaningful disappointment.

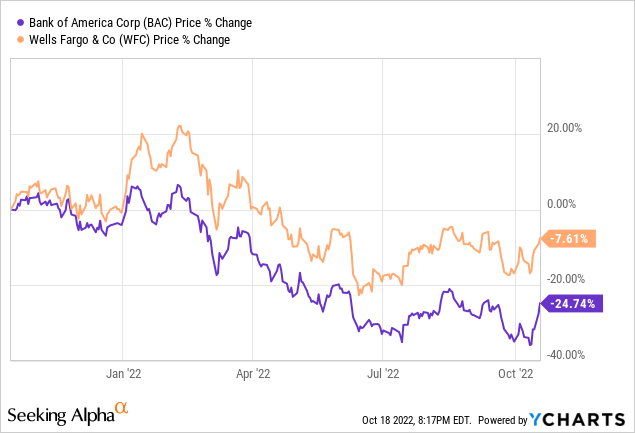

So why did the stock jump 6% on Monday and more on Tuesday? The answer put forward was that it could have been worse. Analysts had published low enough forecasts that this relatively weak performance could be packaged as an earnings “beat,” That’s one of the more overused descriptions of earnings results. The stock was recently down around 40% from its 52-week high just over $50, so maybe looking up at the world from flat on its back the modest earnings decline looks like an accomplishment. Don’t kid yourself. It wasn’t. Here’s the one year chart of Bank of America compared to Wells Fargo (WFC), the peer which most closely resembles BAC in having a large Main Street consumer banking unit:

You can see clearly that while the overall environment dragged down the performance of both banks, Wells Fargo did much better. I had expected this as I wrote here in September, as the overall pattern was that Main Street banks performed well in the basic business of consumer and corporate loans but were dragged down by a virtual collapse in underwriting as the IPO market more or less disappeared. Bank of America also performed poorly in Wealth Management while Wells Fargo was pulled down by the decline in the mortgage market. The reasonable expectation was that with their many consumer branches these two companies would do extremely well in Net Interest Income and Net Interest Margin. Both did so.

Both BAC and WFC benefit from a large depositor base, with over 50% being in checking accounts, a fact frequently cited by leading bank analyst Mike Mayo who continues to rank Bank of America as his top choice among the major banks. For Q3 BAC saw its NII increase 24% while its NIM rose 24 basis points. Both numbers were aided by Fed rate increases which enabled loan income to rise while the sticky depositor base held funding costs low. Again, BAC and WFC, with their large percentage of deposits in checking accounts, rank 1 and 2 for lowest cost of funds at $.09 and $.10. Will this persist?

Mike Mayo thinks that any rise in payouts to depositors will be gradual. There were, in short, no problems or disappointments in interest income and margins, at least in Q3. Don’t get me wrong. This was a good thing. The old banking adage was to follow the 3-6-3 rule: borrow at 3%, lend at 6%, and be on the golf course by 3 o’clock. The numbers have changed a bit over the years, with low interest rates, but the game is the same. You might throw in something about paying a 3% dividend. The trouble is that nothing has worked quite right for banks over the past decade and a half since the great financial crisis in which banks were featured. The rising rate climate was their chance to step on the gas and reward shareholders. It hasn’t happened. Instead I think Bank of America continues to struggle with a basic principle of capitalism which involves investors being rewarded fairly for the use of their capital.

From my perspective, the Bank of America quarter was OK at best. To me the fact that BAC made reasonable returns was a dog-bites-man story. They did the obvious things and got the obvious results. It would have been miraculous if they hadn’t. It was a simple matter of riding the wave of rising rates. The story is short and simple. Non-interest earnings were virtually non-existent. Net Interest Income (NII) was excellent. This was basically true of all the major banks. What mattered was the relative importance of the various businesses that make up a mega-cap bank. The investment banks, Goldman Sachs (GS) and Morgan Stanley (MS) had little or no consumer banking to fall back on as IPOs just disappeared. Wells Fargo and Bank of America took advantage of their large Main Street banking units.

So far in 2022 the market performance of bank stocks places them exactly in the middle at number 7 of the 13 major industry groups. Banks are down a bit over 15% for the year, perhaps a little less as they have rallied strongly for days mainly on the results at BAC. That’s a couple of points better than the S&P 500 (SPY). The leading industry is, of course, energy, up about 30% after leading last year at positive 54%. Energy is a very small part of the market, of course, and is benefiting from a one-of-kind situation. All other industries are down, with utilities, consumer staples, and health care coming just behind energy in the less bad category while technology and consumer discretionary are at the bottom. That’s hardly the picture of a healthy economy from which banks should benefit.

Why is it that banks in general are right in the middle of industry groups? You can argue it a few ways. One is that the market expects that banks will continue with the lukewarm performance of the past decade. Another is that the future results for banks are highly unpredictable and somewhat binary, with a chance of a very good performance if high rates and high profits continue and a more or less equal chance for quite poor performance if the Fed overshoots and the economy tanks. The answer to this question will determine whether Bank of America will prove to be a good investment going forward or continues to be a very disappointing one. For now, though, let’s give credit where credit is due while pointing out that Bank of America mostly performed decently thanks to outside influences.

The Message Behind The Numbers

Quarterly earnings reports are a bit like Presidential debates. First you get the predictions, then you get the actual performance. As soon as the numbers are out, you get the spin doctors explaining how they would like you to interpret what happened. It’s axiomatic that they emphasize the numbers which were good and can be spun to the narrative they want to present. It is equally axiomatic that they evade or talk around numbers and trends they don’t want you to think about. Some companies say very little. Some say nothing at all. The approach at Bank of America is to bury you in an avalanche of details in my opinion, most of which are to guide Wall Street analysts. I think much of the conversation is irrelevant to actual shareholders. The CEO/CFO narrative isn’t designed to provide useful information. It’s designed to give you a headache. The only way to see this is to read the whole management presentation. I don’t feel able to copy enough in the middle of an article to deliver the halting, distracting tone of the BAC presentation. Read the SA News link here, if you want to get the overall picture. Take an aspirin first.

Most of the key facts are mentioned in the first paragraph above. Total earnings and earnings per share were down. Period. No problem. BAC had prepared you for this by guiding down well in advance. Presidential debate staffers do that too. They emphasize the things their candidates can’t be expected to do well and suggest you grade on a curve. As CEO Moynihan explained in the earnings call this was nothing, really, because it stemmed from raising reserves as they had suddenly realized that there is rising risk in the economy. That was an about face after reducing reserves last quarter. They are finally getting the handle on CET1, which rose from 10.4 to 11, about a year too late to make it possible for BAC to do meaningful buybacks this year. Great. Good for them.

I mentioned in my earlier article on the major banks that I saw the BAC problem with CET1 and this year’s upcoming Fed stress tests as early as last year. I would love to know the inside story on that. My best guess is that the man who was tasked with whispering “Don’t forget the stress tests” five times a day in Brian Moynihan’s left ear was enjoying BAC’s vaunted work-from-home policy. The earnings call also included lots of numbers which were measurable against, well, nothing. Wealth management added 400 advisors, but Wealth Management made less money than the year before. Market conditions were unfavorable, you see. How should I reconcile those two facts in a way that helps me understand what I am supposed to think?

Checking accounts increased with 400,000 new depositors. That’s a positive number if they can loan the money out satisfactorily, but what about Jamie Dimon’s recent prediction that government fiscal largesse would stop sloshing through the markets around the middle of 2023? Is there a message in those two phenomena? What does it mean that credit card and loan delinquencies were rising? Oh, maybe that has something to do with the added reserves which pulled earnings into negative territory.

The trouble with the details that both CEO and CFO trot out at every earnings call – things like spending on employees, technology, marketing, and new and renovated financial centers to “enhance customer experience” – is that they are all things that are ongoing and go without saying. Sure, I like enhancing customer experience as much as the next guy, but it doesn’t do much as part of the report to me as a shareholder. It’s a little bit like missing my wife’s birthday but reminding her that I took care of state and local car sticker renewals and paid the yard guy. Don’t try that, guys.

How About Shareholders?

There’s no doubt that Bank of America flacks could put together a rebuttal/explanation for my fifteen or twenty miffs. Perhaps they are minor taken one by one but taken all together they raise an important question: where are shareholders in all this? As a shareholder myself I feel like a shabby cousin who turned up unexpectedly and uninvited at a family gathering. As a capitalist, however, I don’t see myself that way.

Picking through all the numbers it’s clear that everything positive is pretty much grounded in the one thing over which BAC has no control: rising interest rates. That’s why the results of Main Street banks look so similar while the results of integrated banks so closely track the level of their business that is in consumer banking. The major thing that undercuts BAC’s performance from the shareholder point of view is the one big thing over which they should have had control: the fact that they flubbed the stress tests back in February. For this reason I think we should consider bank management, including BAC CEO Brian Moynihan, to be on probation.

Banks as a whole occupy an odd position in the markets. They are to some degree cyclicals which should do well in a hot economy with high and rising rates. If such an economic environment continues, Bank of America will probably do well in spite of itself. If a major recession occurs, clearly a current worry as added reserves show, who knows? Mike Mayo takes the view that BAC should continue to do well. I am less sure. The only part of it under BAC’s control is the quality of its corporate and individual loan portfolio. I have no visibility on that and have to take it on their word that it’s OK.

The other problem of banks is that they are as much a utility as a cyclical and they are utilities of the worst possible kind. They are set up to be blamed and punished for everything, and unlike energy-oriented utilities they are never rewarded for actions which serve the public good. Meanwhile their regulators have increasingly tied their hands when it comes to making decisions. Jamie Dimon kicked up a ruckus about this. Brian Moynihan quietly appealed the Fed requirement for a higher buffer against bad times then accepted the Fed’s denial of BAC’s appeal. I’d argue that they caved. Shareholders are unlikely to get a better deal any time soon, especially if the economy turns down.

The trouble with the constraints on buybacks is that buybacks have been the major source of earnings per share growth over the past decade. BAC was the leader at one point and at times spent more than 100% of earnings on shareholder return combining dividends and buybacks. A 7% buyback is a permanent 7% increase in per share earnings and permits a 7% increase in dividends without more aggregate cash going out the door. Without buybacks, Bank of America is like a preferred stock or bond. Its only value derives from its relatively safe and slow-growing dividend. Right now the yield of that meager dividend is 2.5%. With high inflation, US Treasuries of all maturities longer than 3 months yield at least 4% and many very safe areas of the fixed income markets beat the deal offered by BAC dividends. BAC’s cash return guarantees that its shareholders lose heavily to inflation, and that’s before the taking into account relative collapse of its stock.

I’m made aware of this situation with each successive earnings call. Look as I will, I can’t see myself as a shareholder anywhere in it. Everybody else comes ahead of shareholders. Here’s the way CFO Alastair Borthwick put it the case on buybacks:

We paid out $1.8 billion in common dividends. We bought back $450 million in gross share repurchases, and that covered our employee issuances in the quarter, leaving no dilutive impact for shareholders.”

The key word here is “gross.” To get the paltry level of net buybacks you have to do some math on shares outstanding and guess how much is not yet paid out to executives. At least those upper level employees will be happy and appreciated at home. Would somebody tell me what they accomplished to deserve getting buybacks? Why weren’t shareholders the ones benefitting from buybacks? Should we just feel happy that BAC bought back enough shares to cover employee issuances and avoid dilutive impact?

Having bought Bank of America at a good moment in the middle of the last decade I am stuck in a position with no negative tranches and well over half my position consisting of long term capital gains. Selling would return close to 25% of my capital to the IRS. My yield on cost is in the middle teens, which is fine. I was lucky when I bought, I suppose, and Bank of America didn’t always have the arguably shareholder-unfriendly view it now has. It’s the number one stock on my Potential Source of Funds list, but I have literally never sold a position which required me to give up so much in cap gains taxes. The main reason to hold is that the price is low enough to provide some support. For now the odds favor hanging on and seeing if the rising ride of interest rates can lift all boats. I would be much less grumpy to see BAC management shape up, make more money, and send a chunk of it to me.

Show Me The Money

Erika Najarian put it succinctly in the Q and A part of the earnings call.

And I’m wondering, do we need to see Bank of America get to that 11.4% before heavier buyback activity? Or do you think you could manage the heavier buyback activity as you build to that 11.4% CET1 by January 1, 2024?”

Here’s the response by CEO Brian Moynihan:

So we bought back shares this quarter and still grew the capital. Our job is to drive our company to serve our customers in that first order of business for our capital has always helped the growth in the balance sheet, especially on the lending and market side. And so you should expect that buybacks will continue to increase. But remember, we are now sitting above what we are supposed to be sitting at on 1/1/2024. And so next year is already here. So obviously, the trade between building the buffer up a little bit more, as you said, from where we are now to [50] basis points over the requirement is a little bit different. We already exceeded the requirements. So we’ll put a little bit towards the buffer. We’ll support the organic growth a little bit towards a buffer and the use of rest to send back to you guys.”

Do you hear the same hesitancy in that answer that I do? There’s no mention of net buyback dollar amounts here or elsewhere in the earnings call. Moynihan can’t stop himself from putting the Fed’s buffer first and his own preference for organic growth second. Something that can be made to look like organic growth, you see, is the basis of bonuses and shares for leadership. In truth, I think it’s reducing the denominator through buybacks that would provide the greatest benefit for shareholders. Is there anybody at BAC who speaks up for them? A sort of shareholder ombudsman might be a good idea. I sort of feel like the guy who speaks up at the table in The Godfather to say, “After all, we aren’t communists.” All the mob guys got a good laugh out of it.

Be the first to comment